.

By BILL TAMMEUS

Author of Love, Loss and Endurance

In his Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln looked not just to the appalling carnage of the still-unwon Civil War but also to this split nation’s uncertain future.

“It is,” he said, “for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work” of freedom for which Union soldiers fought.

Lincoln’s charge still is our charge. But freedom for and from what?

In many ways the answer continues to be freedom from evils America’s slaves experienced for so long—the terrorism and extremism of white supremacy, of injustice, of economic, educational and spiritual degradation.

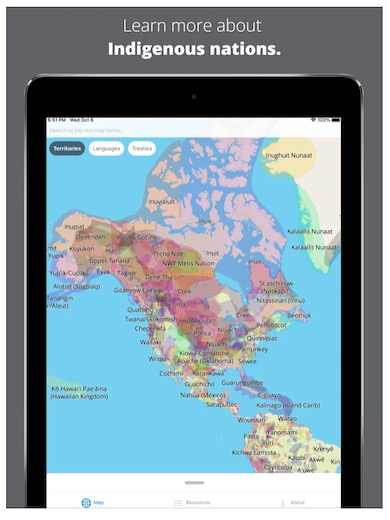

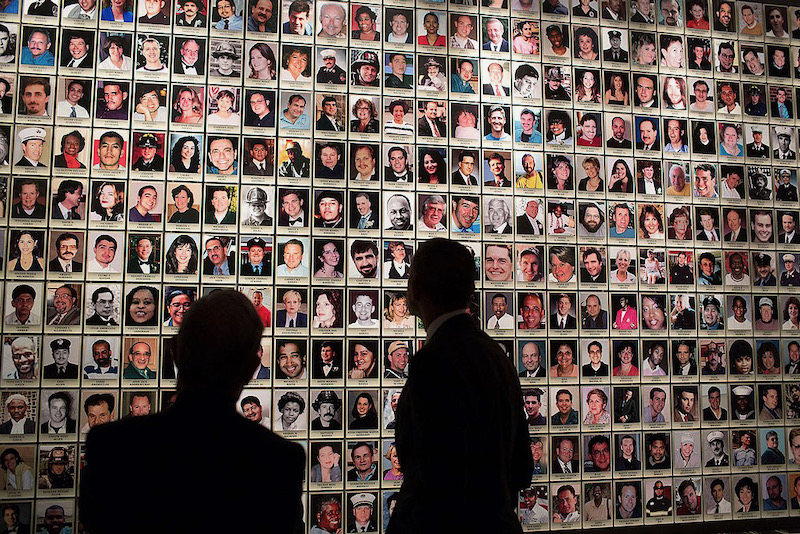

In my book, Love, Loss and Endurance: A 9/11 Story of Resilience and Hope in an Age of Anxiety, I describe the murder of my nephew in the 9/11 terrorist attacks, but I also explore the roots of radicalism and suggest a few ways we might try to unplug extremism.

Those suggestions also can help Americans complete what Lincoln called our “unfinished work.”

Bridging Our Divides—Together

Here’s a summary of the recommendations in my book:

1. Respect (and love) others. Simple, right? Well, in my Christian tradition, one of the most difficult tasks we are given is not just to treat others with respect but to love them, which means always having their best interests at heart. But on what basis do we do that? One answer is that Scripture tells us that all people are created in God’s image. One way Christians think about is to say that they’re obliged to see Christ in every human being, Christian or not. And, having recognized Christ in another, the last thing we should want to do is to insult, injure or murder that person.

2. Become more religiously literate because our country is becoming more religiously diverse. Our human tendency is to fear what we don’t know. To break that habit, it’s necessary to commit ourselves to learning about religious traditions and philosophical worldviews beyond our own. There are many ways to do that. One is simply to read some helpful books. I’d start with Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know—And Doesn’t, by Stephen Prothero. Then get outside your comfortable religious and worldview surroundings. The most obvious way is to travel. Each time you experience a religious tradition beyond your own you gain not only knowledge but also the idea that people very much like yourself have made other religious choices that don’t threaten the safety and peace of their neighbors. That means you don’t need to exterminate them or push them out of town.

3. Engage in interfaith dialogue and cooperation. Many communities have interfaith organizations that promote understanding. The idea isn’t to work for the mashing together of different religions into one broad syncretistic mess. Rather, it’s for people of different faith traditions to know and to be known. It’s to understand the many different approaches to religion that people of goodwill adopt, an understanding that should lead to a bit of humility about whether our own choices are also God’s direction for everyone else.

4. Teach your children and grandchildren well. Specific hatreds must be taught. And children will learn hatred from people around them if they’re not taught respect, love and compassion — and, sadly, sometimes even if they are. At the very least, they must learn tolerance, which is a terrifically low standard but at least is to be preferred to contempt.

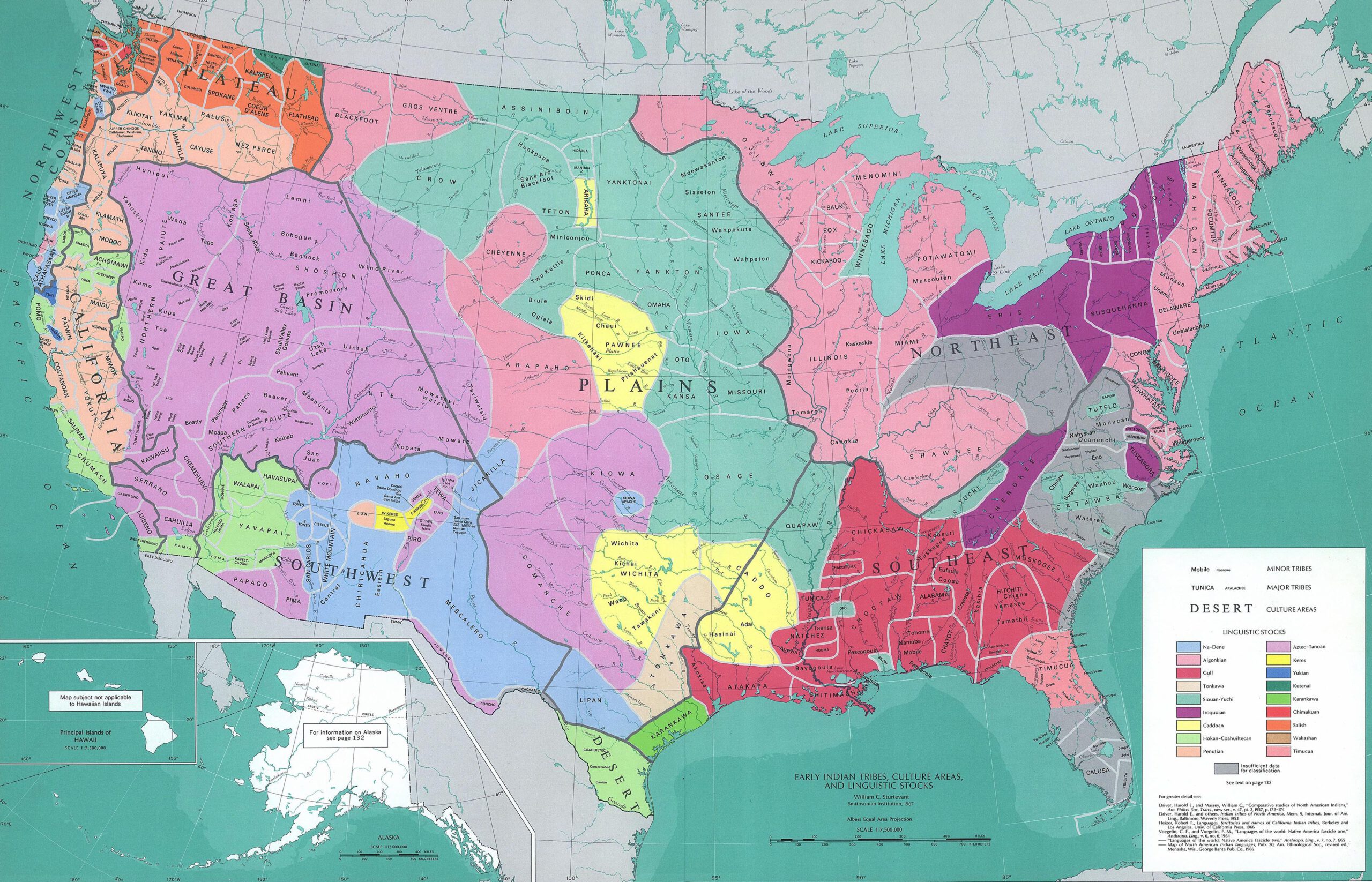

5. Deepen your knowledge of both American and world history. A fair amount of global terrorism is tied to the shockwaves that have radiated across the nation and around the globe from historical events about which many Americans seem to know little or nothing. That’s particularly true about geopolitical and religious history in developing nations, including parts of the Middle East. The list of problematic, even if sometimes defensible, actions taken by the U.S. over its history is long indeed, and despite all the great work here and around the world that the U.S. has done, it has made many enemies. I’m not suggesting we forgive acts of terrorism or that we consider American foreign policy simply one disaster after another. That would be both wrong and unfair. But it’s important to know both American and world history to understand what sometimes motivates America’s declared enemies.

6. In this remarkably divisive time in our nation, become competent in civil discourse, which may be next to impossible using social media. The practice of civility can teach us how to listen carefully and to appreciate points of view not our own. That, in turn, can lead us away from any tendency to align ourselves with people who imagine that they know all the answers. For help with this, start with You Don’t Have to Be Wrong for Me to Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, by Rabbi Brad Hirschfield.

7. Spend time with people who have experienced profound grief. It can open our eyes to the countless ways that death — particularly unexpected, violent death — can affect almost every aspect of the lives of survivors. You may not know anyone who lost family members on 9/11 or in other terrorist attacks, but there are lots of surviving family members of those who died in attacks in El Paso, Pittsburgh, Poway, Charleston, Kansas City and on and on. If there’s an opportunity, meet some of them. Talk with them, if they’re willing to do that, but only if they’re willing. Let them tell you their story.

Now add your own ideas to this list and go be part of the solution.

Bill Tammeus, an award-winning columnist formerly with The Kansas City Star, writes the “Faith Matters” blog for The Star’s website and book reviews for The National Catholic Reporter and for The Presbyterian Outlook. His latest book is Love, Loss and Endurance: A 9/11 Story of Resilience and Hope in an Age of Anxiety. Email him at [email protected].

.

Care to Read More in our Fourth of July 2023 series on Lincoln?

Whatever you choose to read next, you will find the following links to the other 2023 columns at the bottom of each page:

Lincoln scholar Duncan Newcomer’s introduction to this series includes a salute to Braver Angels, a nationwide nonprofit dedicated to de-polarizing American politics that is gathering from across the country for a major conference at Gettysburg this week.

Duncan also writes about: What were Lincoln’s hopes for our nation?

And, he explores: What were Lincoln’s core values?

Then, journalist and author Bill Tammeus writes about how Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address still calls us to reach out to one another.

Journalist and author Martin Davis asks: Are our battle-scarred American roads capable of carrying us toward unity?

Author and leadership coach Larry Buxton writes about: Growing up and growing wise with Abraham Lincoln

Columnist and editor Judith Pratt recalls: Hearing our Civil War stories shared generation to generation.

Attorney and community activist Mark Jacobs writes about: How Lincoln’s astonishing resilience and perseverance inspires me today

.

.

Want the book?

Want the book?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions.

.