How one crucial phone call spurred a movement

Our world desperately needs to learn from peacemakers! Just look at the global headlines, each morning, and you’ll agree: There must be a better way to live together.

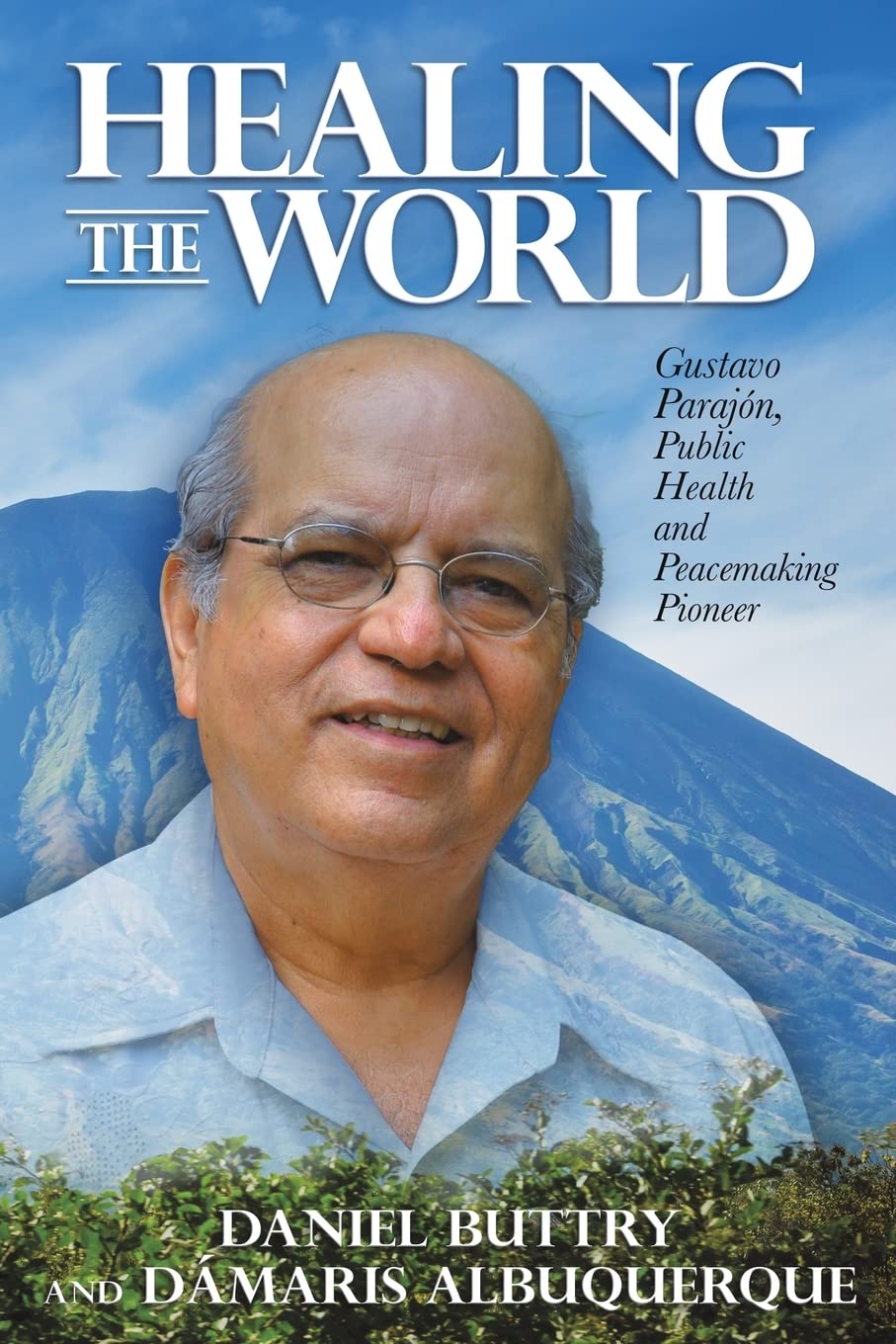

That’s why—to start this new year—our publishing house is launching: Healing the World—Gustavo Parajón, Public Health and Peacemaking Pioneer. In this inspiring, true biography, readers will meet this seemingly ordinary fellow who stepped into situations that the most courageous warrior would fear—except that Gustavo Parajón was armed with his faith in his God-given talent to defuse confrontation with empathy.

Each week through January 2023, our Read The Spirit online magazine will be publishing inspiring true stories from Gustavo’s life. In this short video, the book’s co-author Daniel Buttry tells about one such moment in which a seemingly small intervention by Gustavo spurred people toward courageous action.