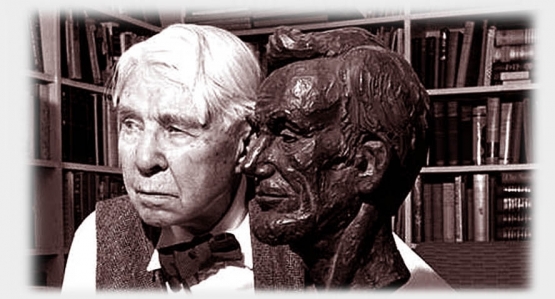

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

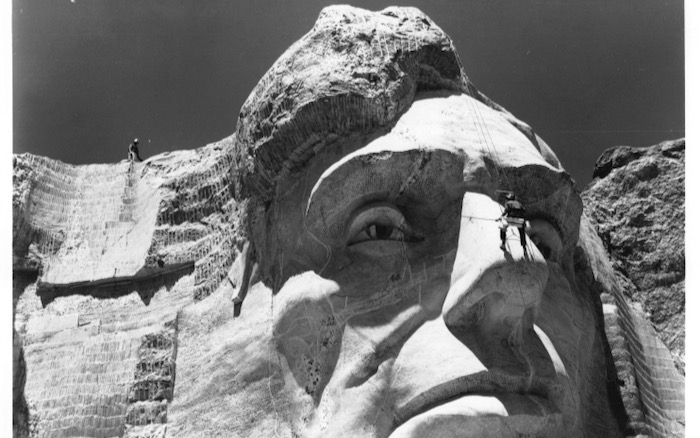

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome. Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome. Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

“I do not think any man has the right thus to insult the feelings, and injure the morals, of the community in which he may live.”

This is on a campaign flier when Lincoln is running for the US Congress in 1846. He’s running against a very popular Methodist minister and revival preacher named Peter Cartwright. When the good reverend began to see that he was losing his bid for Congress, he accused Lincoln of being an infidel, a free thinker, of not being a proper Christian.

So this is Lincoln’s reply, his statement of religious tolerance. He asserts that, while he does not believe in God the way Cartwright does, he would never attack the religious feelings or the morality of those he might disagree with.

Lincoln ran for political office almost ten times in his life. Getting elected or being defeated were among the peak experiences of his life as a politician, and he was first and foremost a politician. And so in the spiritual life of Lincoln we can see much that was most true about him in these election moments.

In his response to the faith-baiting charge of the Rev. Cartwright, we see the secular humanism, the religious tolerance, and the empathy for the religious feelings of others that were bred in the bones of Lincoln.

Cartwright got his “come-up-ence,” it is told, when he asked Lincoln to attend one of his services. Lincoln did. Cartwright, at one point in the service, asked those who felt they were saved and going to heaven to stand. Everyone but Lincoln stood. After all sat down, Cartwright singled out Lincoln as the only one who did not stand. What did he believe?

Lincoln replied that he had been invited to share in a service, he did not expect to be singled out about his beliefs—but it was his belief that he was going to Congress!

Indeed, by a vote of some 6,000 to 4,000, he defeated Cartwright and went to Congress.

Six years later the stakes in national elections were higher. Immigration and race were on the ballot. A secret political movement called the Order of the Star Spangled Banner was formed, later called the Know Nothing Party. They wanted to make it harder for immigrants to become naturalized citizens, and they were for the extension of race-slavery if states wanted it. A minister from Maine, Owen Lovejoy, organized a new political party called the Republican Party, out in Illinois.

At that time Lincoln had a chance to run for the US Senate in the election of 1854. He was on fire about slavery and the Constitution. The other party, called the Democrats, favored allowing the extension of slavery. Southern Democrats wanted it. Northern Democrats thought that the railroads and money would come north if the states opened up into what was called the Kansas and Nebraska Territories.

Lincoln was also fired up because, all across the North, people were being elected to office who wanted to stop the extension of slavery. These people wanted to stop Stephen Douglas, the Democrat, Lincoln’s longtime rival, who was spearheading the drive to open up more slave states if the new states wanted it. Bloody local civil wars already were breaking out in territories where slave and free settlers fought.

Senators were elected by the Illinois Legislature and Lincoln lobbied hard to get them to make him the next US Senator, as a Whig. Lincoln was three votes short on the first ballot. Each ballot after that, pro-slavery forces lobbied and made deals and shifted the votes to the Democrats. Lincoln was losing his bid, and also losing the chance to have a new US Senator who would be against more slavery.

There was one man, a Democrat, who was not like the others. He was not for the extension of slavery.

Lincoln’s problem, of course, was that as a Democrat this man was in the wrong party. Lincoln had worked tirelessly for years to build up the Whig Party, to defeat the Jackson Democrats, in Illinois and across America.

So this new one man, named Lyman Trumbull, had the right ideas, but, for Lincoln, was in the wrong party. Nevertheless, on the 10th ballot Lincoln told his managers to have his core remaining supporters vote for this Democrat.

He was willing to lose in order to further the cause of anti-slavery.

At a reception feting the new Democratic Senator Trumbull, the hostess said to Lincoln, “I know how disappointed you must be.” Lincoln spying the new Senator, smiled and moved forward and said, shaking his hand, “Not too disappointed to congratulate my friend Trumbull.”

In response to this gallant, true, hand-reaching across, those Democrats pledged that in the next election they would support Lincoln, and they did, for President.

Lincoln’s responses to rivals and potential new allies set examples that can light us down through the ages.

This is Duncan Newcomer, and this has been Quiet Fire, the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.