By KEVIN VOLLRATH

Contributing Columnist

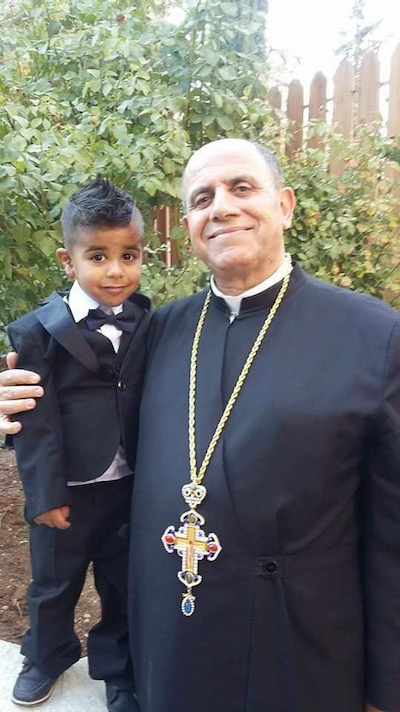

Meet Father Mamdouh Abusada, director of the School of Joy in Beit Sahour, Palestine. Father Mamdouh is a Catholic priest in the historically Christian town of Beit Sahour, just East of Bethlehem. Father Mamdouh was a pastor of family programs in the early-1990’s when he saw a significant need for children with disabilities to receive an education. In 1993 he and his family started the “School of Joy” for children with intellectual disabilities.

Meet Father Mamdouh Abusada, director of the School of Joy in Beit Sahour, Palestine. Father Mamdouh is a Catholic priest in the historically Christian town of Beit Sahour, just East of Bethlehem. Father Mamdouh was a pastor of family programs in the early-1990’s when he saw a significant need for children with disabilities to receive an education. In 1993 he and his family started the “School of Joy” for children with intellectual disabilities.

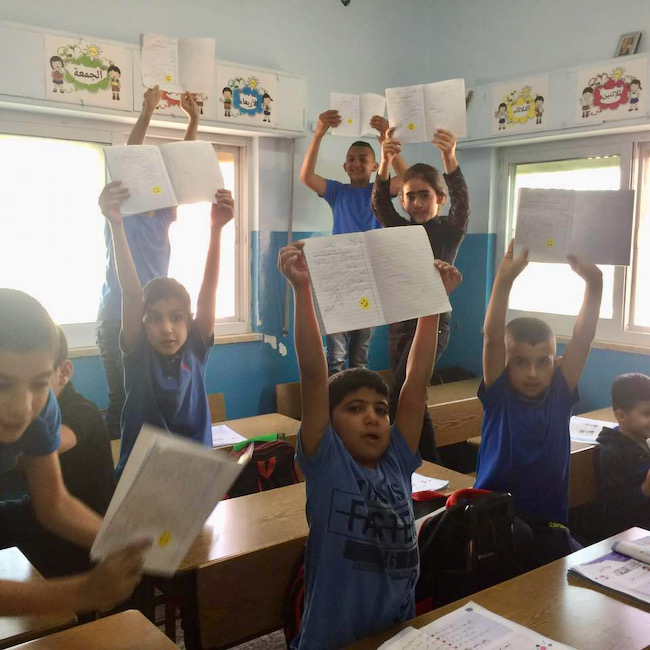

School of Joy now has 51 students, including nine residents, with various intellectual and developmental disabilities. School of Joy teaches Christian as well as Muslim students. Father Mamdouh says that education without discrimination is part of the school’s public witness.

Around the world, people with disabilities experience various forms of stigma and discrimination. That is especially true in Beit Sahour, where poverty affects many families’ diet, health care and the overall learning environment for children. In fact, the founders of the school initially were prompted by a significant number of homeless children with disabilities they noticed in their area. Some of School of Joy’s students were abandoned by their families. Some are orphans.

Father Mamdouh says he sees people changing their attitudes toward their children. To illustrate this, he told me the story of a father, frustrated by the slow learning of one child, who exclaimed, “I wish that God hadn’t given me this child.”

Father Mamdouh responded, “If you don’t see in the face of your child the face of your Lord Jesus, you’ll never be a good man.”

That child eventually joined School of Joy’s vocational training program and learned to work with olive wood. Over the years, he developed his talents as an artisan. Ironically, the child who once had frustrated his father grew up to become the main breadwinner of the family.

As Father Mamdouh puts it, at the School of Joy, “The most neglected become the most important.”

Old biases against the disabled continue in many families. Parents may even try to hide one child’s disability. Sometimes staff from School of Joy can only discover a child in need of education upon visiting families in their home. As a result, the School of Joy has on staff a psychologist and social worker to help children and their families.

Stigma is not School of Joy’s only challenge. Teaching online during the COVID pandemic has been as difficult for School of Joy as for schools in other parts of the world. The staff decided they could host just 10 students in person and would have all the others learn from home, which required extra planning for teachers and especially for low-income families. Few families can provide Zoom for their children’s classwork because of daily challenges with maintaining electricity and the Internet in the West Bank.

Funding is the school’s most significant need, Father Mamdouh says. Families often are only able to contribute small amounts to the cost of their children’s education. Donors are the main backbone of the school’s budget, but a typical donor only sponsors a child for a year or two, requiring constant attention to fund raising. Since tourism to Bethlehem has dwindled during the pandemic, this also has decreased awareness of the school among foreign visitors.

All of these dynamics also must be navigated through the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the resulting maze of legal and financial requirements both for students and the school itself. Farah’s story illustrates just one of the complications. She has been a student for several years at School of Joy after having been refused enrollment in public schools. Farah was caught in a legal requirement that all public-school students must have a birth certificate. She does not have one because birth certificates in the region must name both parents and Farah’s unmarried mother declined to name the father. Thus, she has no birth certificate and no access to local public schools. Father Mamdouh repeatedly tried to help obtain a waiver for Farah from authorities, but so far has been unsuccessful.

When asked why Father Mamdouh is so committed to this work, he says, “We’re human. Jesus came for all. Humanity is very important to me. Humans should treat everyone the same, without discrimination. We’ll all be okay if we do this.”

School of Joy is one of many institutions in the Bethlehem area in which Christians and Muslims work together. According to Father Mamdouh, the Church can play a unique role in helping people to realize their shared humanity. That requires, he says, seeing the face of the Lord Jesus in the face of one’s neighbor, whether Christian, Muslim or Jewish, whether able-bodied or disabled.

If you or your community would like to visit the School of Joy on a trip to the Holy Land, contact us at Churches for Middle East Peace (CMEP).