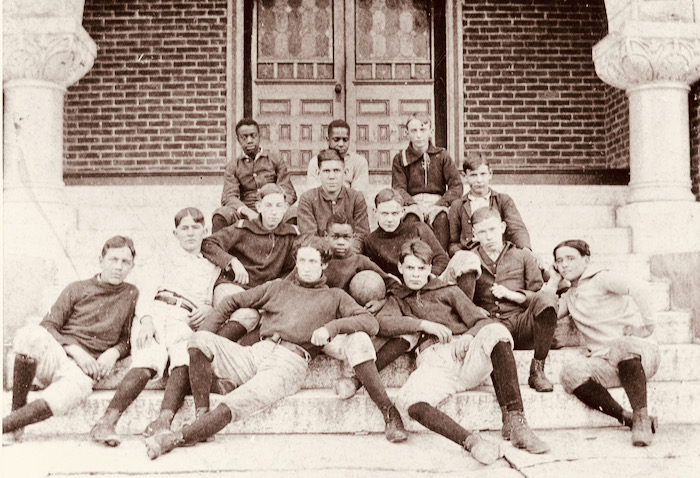

Wilderness Church at Chancellorsville was the center of a stand made by some Union forces after Confederates under Stonewall Jackson made a surprise flank attack. (Click on the photo to learn more about the battle from Wikipedia.)

By MARTIN DAVIS

Author of 30 Days with America’s High School Coaches

In Spotsylvania, Virginia, a sign reading “Crossroads of the Civil War” greets visitors driving into the county from the west on State Route 3.

They are driving through land that Gens. Robert E. Lee and Joseph Hooker would still recognize, as it is little changed since they clashed in April 1863 at Chancellorsville, from which Lee turned north and toward his fateful battle at Gettysburg.

There is no such sign to greet visitors traveling north or south through the county on Interstate 95. And while Lee and Gen. Ambrose Burnside—who collided in Fredericksburg in December 1862—would recognize the general terrain along the interstate, they certainly wouldn’t recognize the region.

As a journalist, Martin Davis is an expert at inviting Americans of all political and cultural backgrounds to speak honestly about their lives. That’s what he did in his book 30 Days with America’s High School Coaches. Click on the cover to visit the book’s Amazon page.

This is the area that I call home. In local-government speak, it’s Planning District 16. In everyday speak, it’s the embodiment of a divided America.

Travel five miles east and west of I-95, and you’ll find highly educated, well-paid, professionals; as well as college-educated middle-class citizens. Many travel 50-or-more miles north to work every day. They settled here for plentiful land and relatively inexpensive homes. They were also attracted to good school divisions, the beautiful Rappahannock River, and the city of Fredericksburg with its arts and food scene.

The explosion in growth, the accompanying money, and the educational pedigree created a class of people unsympathetic to the Lost Cause. Their economic and social dominance also created a veneer of peace over the land that once played host to the battles of Chancellorsville (31,000 casualties), Wilderness (29,000 casualties), Fredericksburg (18,500 casualties), and Spotsylvania Courthouse (30,000 casualties).

The foes of Union, however, never went away. A small percentage of residents still fly confederate flags, and a larger percentage—through either quiet affirmation or silence in the face of pro-confederate propaganda—ensured the county remained a welcome locale for the very people who split Lincoln’s beloved Union in 1861.

Alongside these neo-confederates have risen the Christian Nationalists, the evangelical fundamentalists and the Trumpists. Donald Trump carried both Spotsylvania and Stafford counties in 2016. He carried Spotsylvania again in 2020, but by a smaller margin, and he lost to Biden—barely—in Stafford. Fredericksburg went Democratic in both races. (See here and here for a closer look.)

And the tensions that have erupted match those leading up to the Civil War in tone, if not in ferocity. I’ve spent the past two years reporting on these controversies—mostly in local school boards.

In the midst of such battles, I often wonder where the next Lincoln will come from—that one voice that can craft a vision forward to put down the forces opposed to freedom, and lead those who believe in the ideals of America.

That Lincoln, however, never existed.

Abraham Lincoln’s greatest moments were great in retrospect only. The Gettysburg Address, for example, was so short that most who were there didn’t even hear it. His rise to the presidency in 1861 brought not a unified Republican Party, but rather a divided body politic and a ferocious “team of rivals,” as Doris Kearns Goodwin described in what is surely the best biography of Lincoln over the past 50 years. (With all due respect to David Herbert Donald, and his magnum opus on the 16th president.)

Lincoln doubted himself. He was prone to fits of depression. And the office rarely took as great a toll on any one man as it did him, as side-by-side photos from 1861 and 1865 make clear.

So how did this flawed, frequently politically weak, Lincoln become the Great Man we pine for today in places like my home? The answer lies in understanding what Lincoln had that too many have missed–his Quiet Fire—a side of Lincoln it took scholar Duncan Newcomer to unearth. This quiet fire was a spiritual compass born not of orthodox religion, but an awareness of his own finitude. And his connection to a higher power.

This is the Lincoln we need. And that Lincoln exists.

He lives in the collaborative spirit of The New Dominion Podcast, where the former executive director of the Republican Party of Virginia sits weekly with a card-carrying progressive – the author – and interviews people in our community who understand the glue that is our local Union, and work daily to strengthen it.

He lives in the committed spirits of Nicole Cole, a member of the Spotsylvania School Board who caucuses with Democrats and has been stripped of power by a board majority of Christian Nationalist extremists, and Rich Lieberman, a parent who self-identifies as a conservative. Together, they are addressing issues related to student hunger, and challenging in court the many acts of questionable legality the board majority perpetuates.

And he lives in the life of Scott Mayausky, a Republican Commissioner of the Revenue in Stafford County who is committed to expanding our understanding of those not like us, and finding innovative solutions to taxing problems that unfairly burden the poor.

America the ideal is about e pluribus unum. From the many, one.

But the hard reality of America is that we are forever defined by the roads that we travel through our lives. Roads that bring change, and that remind us of who we once were.

Roads that once carried armies to battle, and that now carry children of all races and classes to school. Roads like Plank and Old Plank roads in Spotsylvania.

Lincoln still travels these roads today. In the lives of those who burn with quiet fire, and a commitment to union. A union of shared humanity.

Martin Davis is an award-winning journalist, founder of F2S, and co-founder of the New Dominion Podcast. His first book, 30 Days with America’s High School Coaches, examined how coaches are raising the next generation of leaders. His next book will explore the disconnect between education policy, and life in the classroom. Visit him at https://www.martindavisauthor.com.

.

Care to Read More in our Fourth of July 2023 series on Lincoln?

Whatever you choose to read next, you will find the following links to the other 2023 columns at the bottom of each page:

Lincoln scholar Duncan Newcomer’s introduction to this series includes a salute to Braver Angels, a nationwide nonprofit dedicated to de-polarizing American politics that is gathering from across the country for a major conference at Gettysburg this week.

Duncan also writes about: What were Lincoln’s hopes for our nation?

And, he explores: What were Lincoln’s core values?

Then, journalist and author Bill Tammeus writes about how Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address still calls us to reach out to one another.

Journalist and author Martin Davis asks: Are our battle-scarred American roads capable of carrying us toward unity?

Author and leadership coach Larry Buxton writes about: Growing up and growing wise with Abraham Lincoln

Columnist and editor Judith Pratt recalls: Hearing our Civil War stories shared generation to generation.

Attorney and community activist Mark Jacobs writes about: How Lincoln’s astonishing resilience and perseverance inspires me today

.

.

Want the book?

Want the book?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions.

.