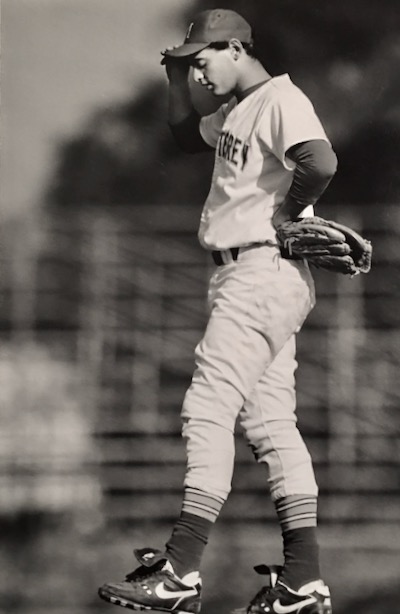

“PLAY BALL!” Action at Frank E. Sollecito Ballpark in Monterey, California.

.

By MARTIN DAVIS

Contributing Columnist

Yes, high school baseball is just a game—but baseball also is life.

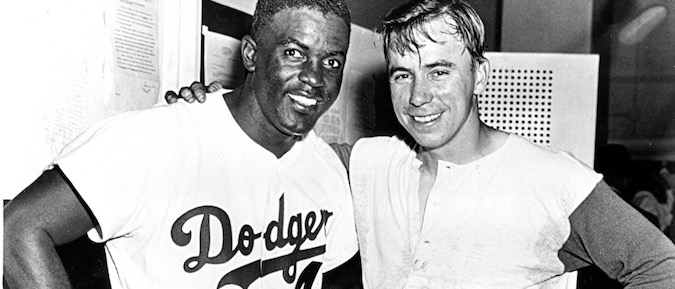

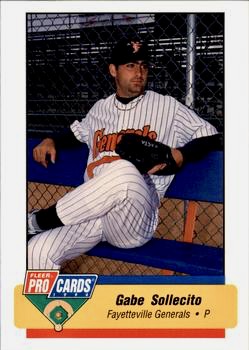

Frank “Frankie” Sollecito in his pitching prime.

In our most troubled days, it’s a game that defines who we are and transforms both players and their communities forever. That certainly was true of the relationship between Michael Groves—head baseball coach at Monterey High School and a member of the California Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame—and a once-in-a-lifetime student-athlete, Frankie Sollecito. Here is the story of the tragedy that united them—and how that event continues to shape new generations three decades later.

.

On an April afternoon in 1988 during a regular-season game against Bellarmine College Prep, Frank “Frankie” Sollecito Jr. was struggling. Something he didn’t often do.

At 6’5” and 230 pounds, Sollecito was the type of athlete who played a level or two above his peers. That talent had been recognized and rewarded by UCLA and Oklahoma—powerhouse football programs that wanted him to play tight end. He was also a straight-A student, and a “character,” whose humor and wisdom were beyond his years.

Sollecito, however, had other ideas. He had accepted a baseball scholarship and would enroll in the fall at UC Berkeley—two hours up the California coast from his home in Monterey.

None of that was on his mind, however, that day. Coming off the mound in the 5th inning, Frankie knew he was in trouble.

“Coach,” Sollecito said to Michael Groves, “I’m exhausted.”

Groves told him to sit; someone else could close out the game.

“No,” Sollectio said. He was going to finish that tight game that ended in a Monterey one-run loss. That night Groves called the young man’s parents, only to discover that they, too, had concerns. Frankie had recently had a dental procedure that was not healing properly.

The next day at practice, Groves saw Sollecito just sitting in the outfield. Again, he was complaining of exhaustion.

They sent him straight to the hospital. Later that evening, test results showed that Frankie Sollecito Jr., at 18 years of age, had leukemia.

The next month for Frankie was a gauntlet of hospital stays and chemotherapy.

His teammates at Monterey High School kept playing. And Coach Groves kept doing what he always does—giving of himself. Every afternoon, he showed up at the school’s downtown baseball field. Oftentimes he arrived in a suit, coming from a full day’s work running the successful land-use planning firm he founded in 1978. And in the evenings, he would often visit Frankie in the hospital.

In May, the team was in the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) section championship play-offs. Frankie was out of the hospital the week the playoffs began, down nearly 100 pounds from his weight just a month before.

He was there on the bench in street clothes at Salinas Municipal Stadium for the Toreadores’ first round playoff game against Los Gatos. Monterey won 8-3, earning it the right to play the next playoff round at San Jose Municipal Stadium several days later.

However, that is not what was important in the moment. As the team and coach removed equipment from the dugout after the first round victory, Frankie remained seated in street clothes at the far end of the dugout, alone.

As Groves walked back through the dugout, he found Frankie still there, alone and crying.

Groves sat next to him, then stood and held him as he cried, and listened as Frankie whispered, “I can’t do this, Coach. I can’t come to the game and not play.”

But neither could he not be there for his team.

.

The Game

Michael Groves

The second round CIF Championship game against St. Francis High School was tight through the first four innings. Sollecito, still in his street clothes, could do nothing but watch as the Toreadores pitcher walked the first batter of the 5th inning.

“I don’t know what came over me at that moment,” Groves says. “I turned to Frankie and said, ‘let’s get you loosened up so you can play.’ ”

Sollecito looked up and said, “Coach, I don’t have a uniform.”

Groves began unbuttoning his jersey. “You do now.” Inwardly, he had a feeling that this could be Frankie’s last time playing ball.

As Frankie dressed in the Toreadores’ green and gold colors, then made his way to the bullpen to loosen up, the team’s pitcher continued to struggle. He loaded the bases with no one out. Groves made the call to the bullpen.

Over the loudspeaker the announcer’s call came: Frank Sollecito Jr. would be taking the mound for Monterey.

Groves remembers Frankie taking the hill. Word had gotten out about his condition. The MHS fans stood and cheered, but the crowd behind St. Francis was standing and cheering with equal fervor.

Frankie had been severely weakened by a combination chemotherapy-and-bone-marrow-transplant and other treatments. He’d lost considerable velocity on his pitches. Even tougher, he had not thrown competitively since the game against Bellarmine more than a month earlier when he was reaching 92 mph on his fastball—an exceptional velocity for a high school pitcher.

No matter. Frankie forced two quick outs with a ground ball and an infield pop-up, then struck out the last batter. He got out of the inning without giving up a run. Seasoned baseball fans on both sides, many parents, literally erupted over the performance, tears rolling down cheeks, unconcerned with trivial matters such as final scores.

Lacking the strength to pitch the sixth or seventh inning, Groves put him at first base.

It was the last time Frankie Sollecito Jr. would play a high school baseball game.

.

A Passing

Sollecito would bravely battle leukemia for two years. Through it all, he never lost his sense of humor. Still today, those who knew him talk about the funny impersonations that he would do to lift others’ spirits, including the one of Coach Groves, with wild gesticulations loosely mirroring the signs he’d give from his coaching post on the third-base line.

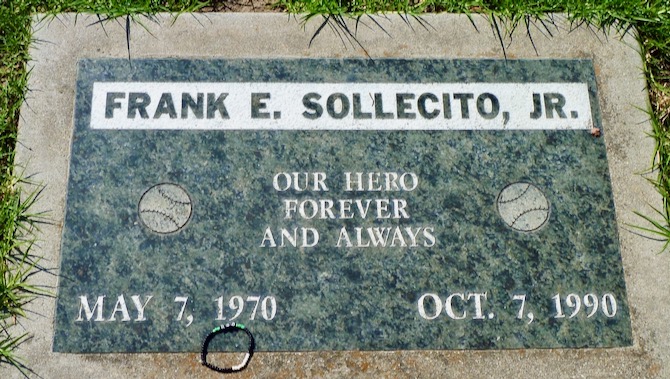

On October 7, 1990—Groves’ birthday—leukemia finally took Frankie’s life. What leukemia didn’t take, however, was Frankie’s spirit.

“I went to his funeral,” Groves recalls. What happened next has never left him. “As I was driving home, he literally appeared in the car with me. It wasn’t a physical presence, but an energy presence.”

Groves swerved off the road, stopped the car, and in those few moments felt Frankie letting him know that “it was going to be ok.”

As a coach, Groves has always stressed the importance of gratitude to his players. He was determined that the joy each moment Frankie had playing would not be lost on future teams.

.

The Transformation

Today, Frankie’s presence is everywhere at Monterey High School ballpark. The field is named in his honor, and a bronze statue of Sollecito stands smiling and holding his glove to his heart, greeting fans upon entry.

Today, Frankie’s presence is everywhere at Monterey High School ballpark. The field is named in his honor, and a bronze statue of Sollecito stands smiling and holding his glove to his heart, greeting fans upon entry.

Every season, wristbands bearing Frankie’s number, 16, are given to the players. One “special” player, who shares Frankie’s character traits, is selected each year to wear the number 16. In addition, a college scholarship bearing Frankie’s name is given each year. Before each game, the team walks past the stands to the statue of Frankie, where they express gratitude, and pray for the FOM (frame of mind) that will pave the way for a successful outing.

The physical reminders, however, don’t always embody an individual’s spirit over time. As students graduated, and younger ones moved in, the spirit of Sollecito began to lose weight with players.

Great stories need to be told and retold over the generations.

For Groves, it all came to a head in 2005. That year, the team had two dominant left-handers and looked to make another run for the CIF sectional championship.

In-fighting had become a problem during this particular year. Finally, with about 8 games to go in the regular season and the Toreadores mired in 4th place, Groves had seen enough. Following a bitter home loss, he ordered the boys to meet him at the ballpark the next day in their tennis shoes. “Don’t bother bringing your baseball cleats.”

Traditionally, the players are running through their warmup routines as Groves arrives and changes into his uniform. When he showed up the following day, no one had tennis shoes on.

Groves is a genial man who rarely lets people see him in a moment of anger. This day, however, he could not hide his frustration. He ordered the boys to take off their cleats, put on their tennis shoes, and together they went on a run.

“We ran around the ballpark and the surrounding El Estero Lake,” Groves says. “Then I ran them into the cemetery across the street from the ballpark and straight to Frankie’s gravesite. I had forgotten that they’re young kids and don’t know the story.

“I told them, ‘Frankie believed it was a privilege to put on an MHS uniform. As long you’re focused on arguing with each other and not playing for each other, you will not be successful.’ After this, I asked the team to make a commitment to each other, and to have gratitude to be able to play this great game in every moment that you are alive, like Frankie did.”

The team went on to win 8 straight league games and a league title, moved on to the CIF sectional play-offs winning four straight championship games, and ultimately the section title. (There is no State championship in California, only sectional championships, owing to the size of the state.) This dynamic team won 12 consecutive games after that run to visit Frankie’s gravesite.

“Each player who wears the MHS green and gold,” says Groves, “learns what Frankie taught his teammates. Wearing that uniform is a privilege and not to be taken lightly. That 2005 season was all inspired by how Frank Sollecito both lived and died.”

.

A Final Thought

The bond between Groves and Frankie Sollecito has shaped the Monterey baseball community for 30 years now. There is much more to the story, however.

As I was finishing this column, I had a phone conversation with Frankie’s parents. They wanted to be sure that people know that Groves’ compassion and support was about so much more than Frankie.

For the two years that Frankie was in treatment at Stanford University Hospital and others, his younger brother, Gabe, had to face life with his mother gone much of the time.

Two years younger than Frankie, Gabe was a remarkable athlete in his own right. He had a hard time getting out from under his brother’s shadow, however.

Two years younger than Frankie, Gabe was a remarkable athlete in his own right. He had a hard time getting out from under his brother’s shadow, however.

His mother remembers Gabe pitching a no-hitter while Frankie was in the hospital, and the local paper noting the achievement, then talking mostly about his brother, Frankie. It tore at his mother’s heart. Michael was there to help him through those difficult years.

Gabe would go on to play at UCLA, and then spend ten years in the minor leagues, rising to AAA—the level just below the majors. He never got the call to play in “The Show,” as the major leagues is referred to by those who play the game.

Now back in Monterey, Gabe is again with Michael Groves—this time as an assistant coach on the baseball team.

This all reflects the way Groves coaches baseball, and teaches his players and everyone he meets, about life.

At the end of the day, we are here for each other.

Every day we have, matters.

“The bottom line,” Groves says, “is this: If you knew it was your last day to play ball, how would you show up?”

.

Care to read more?

Three of our writers, each year, tell fresh stories about the spiritual side of baseball: Martin Davis, Benjamin Pratt and Rodney Curtis.

MARTIN DAVIS—

Davis has written a number of very popular columns over the years about the inspiration that millions of men and women have found through sports. In fact, right now, Martin is working on an entire book of stories specifically focused on high school coaches nationwide—men and women, black and white, famous and unsung heroes alike. This story from Monterey, California, is one of those moving stories he has discovered in his year of virtually crisscrossing America, looking for such transcendent true stories. Want to learn more? Please read this column about Davis’s efforts to launch his new book.

BENJAMIN PRATT—

Author and columnist Benjamin Pratt has written many stories about baseball. Among his most popular:

- Generation to generation, pitching baseballs and values

- Fields of Dreams: In October, our ‘American Odyssey’ calls us home

He also has published several books. Take a look at his Amazon author page.

RODNEY CURTIS—

Author, columnist and photographer Rodney Curtis shares his images and stories in a special section of our ReadTheSpirit magazine.

He also is the author of the baseball-themed Hope’s Diamond: Everything Changes When Hope Comes to Town.