By BENJAMIN PRATT

Contributing Columnist

In a decade of writing columns for ReadTheSpirit magazine—and several books for our publishing house—I have learned that our community of writers is blessed with what our friend Suzy Farbman likes to call GodSigns.

Last week, in the midst of a serious illness—no, it wasn’t COVID—I often thought of that classic image of Charlie Brown shouting “Good Grief!” That was pretty much my spiritual sentiment in the midst of my discomfort and sleepless nights. In fact, one night when I could not sleep, I wrote this column stream-of-consciousness and emailed it to Editor David Crumm.

“Perfect! So timely!” he emailed back.

“Really?”

“Yes, we’ve got a ReadTheSpirit Cover Story on Monday all about how much we need hugs these days, after more than a year in this awful pandemic,” David wrote back.

“I guess that fits,” I wrote back to David. “I’ll trust you, as always, to add a few final touches to have this all make sense.”

Then—as he often does—David dug deeper into that image of Charlie Brown shouting his favorite expression of anguish. And, here’s the GodSign—

We are coming up on the 70th anniversary, next summer, of the first time Charles Schulz put those two famous words in one of Charlie’s dialogue bubbles. You’ll be startled by the coincidence. Here is that original June 2, 1952, comic strip when Charlie utters those words for the first time:

Yes, indeed, there is a connection between what was rumbling around in my sleep-deprived, mid-cold meditations—and our common need for a good old fashioned hug.

But what’s so funny about that? Why have Charlie Brown’s chronic woes made us smile for so long?

The truth is: Life is as much about loss as it is about love and relationships, homes, health, jobs, dreams and all the other wonderful things that bring us joy.

Grief is the normal and natural response to such loss. Grief is that condition we experience when someone or something that matters deeply to us is no longer accessible in the way we want. Grief is painful, but grief also is good because it is the only way we can hope to move from our pain toward the “good” things we treasure such as love, joy, the capacity to risk, engagement, gratitude and generosity.

The refusal to mourn generally leads to bad results. The refusal to face loss leads to bitterness, anger, resentment, fear and attempts to excessively control.

So, I think Charlie Brown is correct. Grief really is good.

I am coming to the conviction that grieving—how we go about moving through losses and how we come to terms with life as it is given—may be the most important spiritual process in our lives. That’s especially true as we age, for as we get older and older the losses come faster and more varied.

Grieving involves the capacity to risk again and again, which is necessary if we hope to rediscover the many joys awaiting us in life.

‘How do we travel this spiritual journey of grief?’

How do we travel this spiritual journey of grief? Or, how can we heal from a broken heart?

First, we need to realize that grieving takes time—an especially hard truth to accept in our age of instant gratification. This process isn’t fast. The time for grieving may be in direct proportion to the intensity of the loss, and, therefore, it is quite personal. As Shakespeare tells us through Othello: “What wound did ever heal but by degrees?” The degrees through which we must journey to heal are often shock, anger, guilt, depression, bargaining, and then maybe healing acceptance.

Losses caused by sin—another’s violation of us or our violation of another—are the most difficult to heal, because these involve forgiveness. Forgiveness then becomes part of the grieving process. Forgiveness is the ability to give up the hope of a different past. Forgiveness is freeing. It is well worth the difficult journey, because forgiveness holds the promise of freeing us to make a trusting leap of faith back into the unknowns of life.

We live our best lives when we dare to hope and risk again.

A Lesson from Ian Fleming’s Bond, James Bond

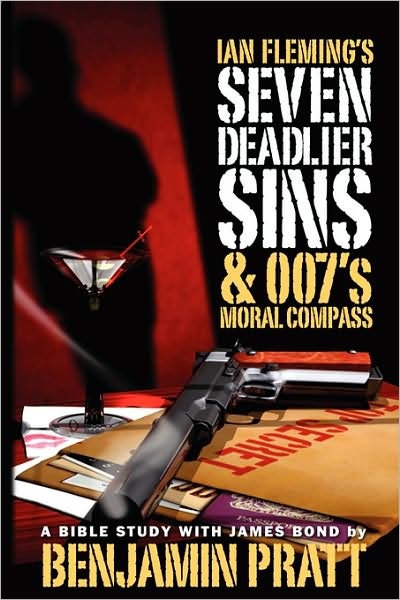

As much as Charles Shultz, the Bible and Shakespeare have shaped my life, I also continue to draw on the literary wisdom of Ian Fleming. And, please note that my own book about Fleming’s spiritual reflections is inspired by his novels, not the movies that always have strayed widely from the original texts.

In Fleming’s cycle of 007 novels, James Bond actually was married—only once and very briefly.

Bond’s wife was shot and killed by Bond’s archenemy on the day of their wedding. Shattered by grief, Bond began to lose his edge: He didn’t show up for work; he began to deal with his loss by drinking, eating too much, gambling, losing his sense of mission.

His boss, M, has Bond examined by a psychiatrist/neurologist named Sir James Malony. This all unfolds in the novel You Only Live Twice. Finally, Malony reports to M that Bond is in shock and that his behavior is quite appropriate.

Then he says the thing that captured my attention: “We must teach them that there is no top to disaster.”

Shocking! Yes, but true. For all the commonplace reassurances that “life will never give you more than you can handle”—in fact, there is no limit to disaster or to grief.

Then, equally as shocking is Sir James Malony’s prescription for Bond: “We must give him an impossible job.” In contrast to our thought that he should take a month on a cruise liner, we hear that “he should be given an impossible job.”

So M sends Bond on a mission to infiltrate and destroy a castle created for people who have lost faith in life, a castle where people can kill themselves. The man who created this castle of death is the same devil who killed Bond’s wife. By confronting and killing the devil of despair, Bond confronts his own despair and is on the road to healing his own wounds. Yes, it is an allegory that is as much about the inner journey as the outer journey.

Turning Outward to Heal

Let me be clear that I am not Sir James Malony—and I would never urge a person I was counseling to get over their grief by immediately throwing themselves into some grand mission. We do need to reach the point of turning outward, but only after we have done the painful interior work of feeling our loss. Talk with friends who have been involved with hospice services. They will tell you that volunteers are not accepted to serve in hospice programs if they are not at least one year away from a significant death among their own loved ones.

Grief takes time, but the outcome we hope eventually will be that outward turning, once again.

Alfred Lord Tennyson said, upon the death of a close friend: “I must love myself into action lest I wither in despair.”

Let me close with a song prayer that captures the tension of longing for safety and yearning to embrace the promise of the future. This song, written by Julie Miller in 1993, was sung by Juliet Turner at the memorial service in Omagh, Northern Ireland, following the market place bombing that killed 29 and injured hundreds.

Broken Dreams

You can have my heart though it isn’t new

Its been used and broken

and only comes in blue

It’s been down a long road

and it got dirty along the way

If I give it to you will you make it clean

and wash the shame away

You can have my heart

if you don’t mind broken things

You can have my life

if you don’t mind these tears

Well I heard that you make old things new

so I give these pieces all to you

If you want it you can have my heart

So beyond repair nothing I could do

I tried to fix it myself but it was only worse

when I got through

Then you walked into my darkness

and you speak words so sweet

and you hold me like a child

till my frozen tears fall at your feet

You can have my heart

if you don’t mind broken things.

.

.

.

.

Care to read more?

Based near Washington D.C., the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Pratt is a retired pastoral counselor with 40 years of experience working with men and women facing a wide range of stresses and tragedies. He is a Fellow of the American Association of Pastoral Counselors and a retired member of the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists. Before COVID struck, he travels widely to work with groups, conferences and other events. Even in the pandemic, he continues this work virtually. He has been a keynote speaker and is a veteran of designing workshops and weekend retreats, which he has conducted nationwide. He writes regularly for ReadTheSpirit online magazine and also is a featured columnist at the website for the popular Day1 radio network.

His book, A Guide for Caregivers, has helped thousands of families nationwide cope with the wide array of challenges involved as more than 50 million of us serve as unpaid caregivers in the U.S. alone. In 2021, Ben will continue to write about caregiving issues for us.

His book, Ian Fleming’s Seven Deadlier Sins and 007’s Moral Compass, explores some of the themes in this week’s Holy Week column, including an in-depth look at Accidie.

If you find these books helpful, and if you suggest that your small group discuss these books, we would love to hear from you about your response, ideas and questions. Or, if you are interested in ordering these books in quantity, please contact us at [email protected]

.

.

I think Ben Pratt knows what he’s talking about, and has many ways of sharing his wisdom so we can all relate.

I always enjoy the way he puts words together to make meaning of the topic at hand. Thank you!

Joyce, you are most welcome. Thank you for the encouraging words.

Thank you Ben

Could not have come at a better time-

Today is the anniversary of the death of my darling Livia

It has been two years

Still grieve her

Best to you and Judith

Nancy

Nancy, Holding you with concern and hope, Benjamin

My dear friend. Thank you for sharing these reflections on grief. We are not good at it, because grief is messy. That’s the message delivered in one of my favorite movies, We Are Marshall.

Marty,

You are absolutely correct that grief at all the surrounds it can be quite messy. I am currently reading a brilliant book by Jodi Picoult called Book of Two Ways. It may be the best thing I’ve read in a long time on the issues dying and the issues of caregiving all related to Egyptology and quantum physics. Quite amazing.