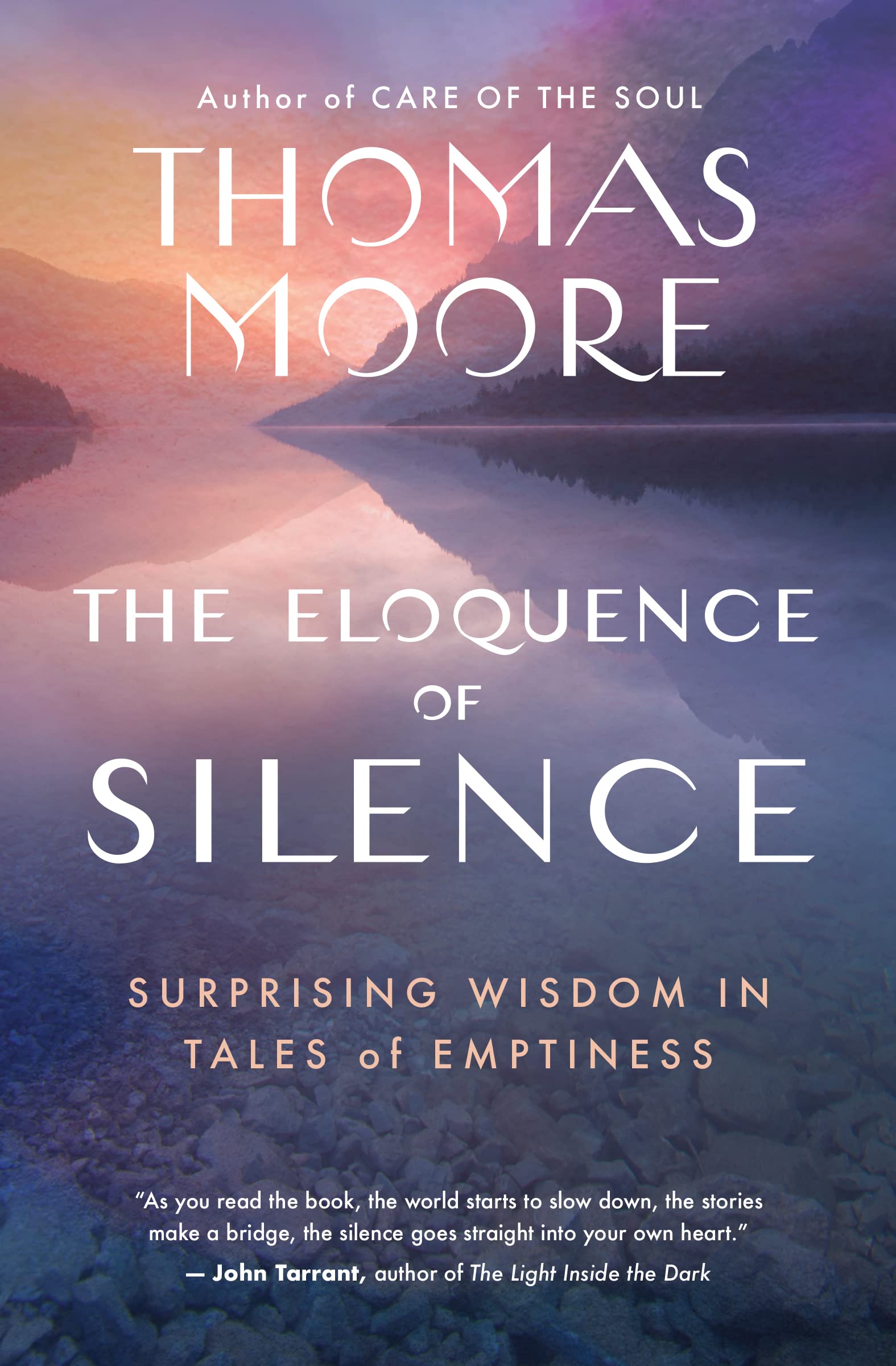

Surprising Wisdom in Tales of Emptiness

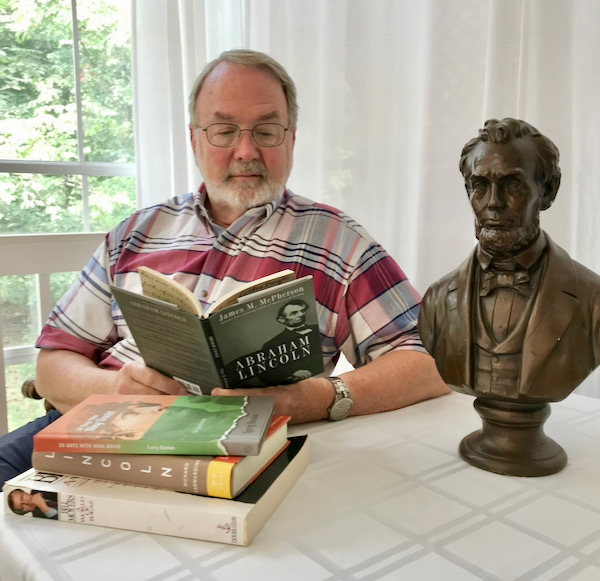

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

“It’s good to talk with you again after 30 years,” I told the bestselling author Thomas Moore as he appeared on my Zoom screen for an interview about his new book, The Eloquence of Silence—Surprising Wisdom in Tales of Emptiness. “Should we make an appointment now to talk in another 30 years?”

Moore laughed. Although he is known for serious spiritual writing, longtime readers enjoy his occasional mischievous wit as well—and it’s certainly evident in his new book, which is full of unexpected twists and turns.

“Let me think,” Moore said. “I’ll be 112 then. I think I’ll have some free time. Sure, let’s set the date.”

The humor we were sharing actually relates to a milestone in Moore’s life that he describes in the opening pages of this new book. Back in 1992, his fifth book had just been published and he traveled all the way from his New England home to some West Coast book events. On his first night out there promoting his book, he showed up for a launch event at a Portland, Oregon, bookstore—where he waited.

And waited.

And no one showed up.

Not one soul.

At that time, Moore shrugged his shoulders and chalked it up to the tough life of a would-be author. So far in his career as a writer, not many people had bought his books, so his expectations were not high for this new book.

Then, on the second night of that 1992 West Coast swing, at a different bookstore this time, hundreds of people showed up. That book—Care of the Soul—soon was on national bestseller lists and, to date, has sold more than 2 million copies. Today, after that classic and more than a dozen other books, we all know that Moore is a major figure in American publishing—period. In the specific circle of spiritual authors, he’s truly a Giant.

But what Moore focuses on in his opening pages of this new book is not the later success. No, instead, he wants us to consider what it felt like on that first night in his lonely vigil, waiting for readers who never arrived. Moore learned far more the first night than he did on the second night of his book tour. Among the lessons he learned that first night was: “That evening of emptiness in Portland taught me not to be attached to obvious and literal success but to remain indifferent to how my work is received, to cherish my creations whether or not anyone shows up to express their approval.”

And, please, read that line again because it’s a truth I’ve learned myself after 50 years as a journalist and editor. As Moore explains, it’s a Buddhist truth that is essential to a balanced life. I have often described that inner balance in the face of the world’s turbulence with a playful metaphor: “having the hide of a rhino.” In his new book, Moore names this more clearly as sunyata, which he describes as reflecting “the great Heart Sutra and the many pages of theoretical writing by the sage Nagarjuna.”

Whatever you prefer to call this timeless spiritual truth, here’s another thought: Sunyata most often is translated as “emptiness”—and Moore and I both know that’s a hard concept to sell to readers. In fact, Moore and his publishing team intentionally moved that word to the subtitle.

Why Emptiness Is Prized

“We had trouble with the title for this book,” Moore told me. “The publisher and my agent and my family all were talking about the title. Sometimes titles just snap into place, but this one was a struggle. The book really is about emptiness but it’s hard to put that word into a book title. Who would buy a book that says it’s about emptiness? That sounds like a blank book.”

Moore paused, then smiled and said, “But I wanted that word somewhere in the title, because this is a book about emptiness. And, in religious tradition, emptiness is prized. And that’s why I’m very happy to see some prominent Zen Buddhists endorsing this book.”

That has been one of Moore’s great talents as a writer and teacher. His story now is well known: Born into an Irish Catholic family in Detroit, he was part of the Order of Servants of Mary (Servites or OSM) for 13 years. He eventually left the order, earned a doctorate in religious studies at Syracuse and worked for many years as a psychotherapist. In his 50s, then, he became world famous for weaving together all the strands from his life, including spirituality and psychology from many traditions.

“In India, there is a tradition of writing long, abstract treatises about emptiness—a treasured tradition that still is studied,” Moore said. “My work in general over all these years is to take these traditions that I think are very rich—and I want to present them in a way that a modern person can understand and apply. I want to use good English to describe these ideas accurately, without all the starchy academic wording, to show how these teachings are relevant today. There are so many ways to approach emptiness. Emptiness is something that can be very spiritually advanced in your spiritual life—or you can start with emptiness as simple as cleaning up your desk, emptying your schedule or cleaning out a closet.”

Wisdom that unfolds over many years

Like many great Christian and Buddhist mystics, Moore’s wisdom has been unfolding ever so slowly over the decades. He was 51 when Care of the Soul made him an internationally influential spiritual teacher. In fact, when I first interviewed Moore in early 1993, there was a lot that I did not know about him—that I have learned subsequently through his writings and that we talked about in our Zoom interview about this new book.

In fact, back in 1992, I had never heard of Thomas Moore. I was the Religion Editor of The Detroit Free Press and was not even aware of his books. There was no Google (1998) or Wikipedia (2001) prompting us with things we should know. There were no emails prompting me, as a journalist, with press releases from publishers. The vast Amazon mothership wasn’t even founded until 1994.

But, in our Free Press newsroom in early 1993, an alert editor called me over to her desk: “I’ve never heard of this guy,” she said, pointing me toward a copy of The New York Times books section laid out on her desk. “But you’re our religion guy and you should know him. After all, he’s a Detroit author, or at least he has family roots here in Detroit—you know, local writer becomes a hit nationally. His book is all over the bestseller lists. We need you to get an interview with him and write up something for our Sunday paper.”

And so I did. I don’t remember much about that interview, nor does Moore himself. Because of some technical glitches in the archives of Detroit newspapers, that resulting article seems to have vanished even from the vast digital archives online these days.

“Talk about emptiness!” I said to Moore in our Zoom conversation. “It’s strange to have a number of years of your public work from that era simply disappear. The story once was there—so very public that it was hand delivered all over the state to a million homes. Now, it’s—gone. Like it never happened.”

‘Hmmm. Makes you think.’

If you have read this far, let me recap: In the opening of this column, so far, there are at least two tales of emptiness that could have served as chapter openers for Moore’s new book. In his 200 pages, Moore’s 40 chapters each begin with a very short tale of emptiness, then he reflects on the wisdom we could glean from those stories and he invites us to continue pondering those stories throughout the rest of our day. At least that was my experience, because I read his book over 40 days as morning meditations.

What are those two tales I’m using to illustrate the kinds of tales you’ll find in his book?

Well, in the opening of this column, there’s the wonderment of the emptiness implied in our scheduling another meeting in 30 years. He would be 112 and I would be 98. But where will we be? Perhaps separated; perhaps together in the great beyond? Where will you and a friend be in 30 years? Hmmm. Now that’s worth pondering.

Or, consider the fact that our first meeting—our first conversation that was delivered to more than 1 million readers of The Free Press 30 years ago—has vanished through a series of archival glitches. Or did that story vanish? Is there someone out there who first “met” Moore through that Free Press story 30 years ago and became one of his millions of readers? In that emptiness—that missing story of our first meeting—were there enduring ripples? Are there readers who intertwined with our story, living with the blessing of having first met Moore in their Sunday Free Press—living with positive Moore memories to this day?

Makes you think.

And, if you like that kind of prompting—and that kind of spiritual reflection—then you’ll love Moore’s new book. There’s something about our very brief cosmic connections across 30 years that is the perfect prelude to The Eloquence of Silence.

A 1945 Newspaper Clipping from the Shores of Lake St. Clair

Since Moore and I were time traveling in our Zoom conversation, we also leaped back 78 years to Michigan’s Lake St. Clair. It’s not as vast as the five so-called Great Lakes, but it’s a very large lake in its own right—and it plays an enormous role in the middle of Moore’s new book. Lake St. Clair is the main character in Chapter 25, called “No One in the Boat.”

“I’m fascinated with that story,” I told Moore. “When we talked 30 years ago, this never came up. And, back then, there was no way to search the archives to find something like this. I know that the story did not appear in Care of the Soul or most of your other books.”

Moore nodded. “It’s a story that has a lot of meaning for me, but it’s not a story I told in my early books.”

Part of the problem—similar to the challenges of explaining words like “emptiness”—is how to tell the story so that readers will understand what Moore himself has gleaned from it. In our interview, he told me that he once resisted telling the story because readers responded to it as proof that God had saved him from the dangerous waters of Lake St. Clair to fulfill his life’s purpose. And, Moore insists, that is not good theology—or, at least, is not his theology.

“But, as I have gotten older, I have begun telling the story,” he said. “I think I’ve told it a few times before this book.”

Later, I checked and he is correct. The first version of the story appeared in a brief passage in his 2004 book Dark Nights of the Soul, including text of a brief 1945 newspaper clipping he has saved:

“A boy whose grandfather gave his life to save him was rescued from Lake St. Clair. The boy, Thomas Moore, 4, son of Ben Moore, was thrown into the water with his grandfather, also named Thomas Moore, when a gust of wind overturned their light boat. The grandfather held the boy afloat above his head as he struggled to keep afloat. The grandfather, exhausted by his efforts, cried out for help.”

Men in another boat on the lake eventually responded, saving the boy. But the grandfather had drowned. The magnitude of that event has stayed with Moore throughout his life. Although he rarely spoke of it in public, he wrote in the 2017 book, Ageless Soul, that not a week has passed in his life that he has not revisited his memories of that day at Lake St. Clair.

“I still wonder about the meaning of it all,” Moore said in our Zoom conversation. “My relatives tell me that I was saved to do the work that I do—but that’s not my version of the story and I think it’s one reason I did not tell the story for many years. My version of the story is that this acquaintance with death made me serious about things. It had that kind of impact. It set my course on a serious life of study and reflection.”

Hmmm. And what are you thinking about this dramatic story? Well, it’s a good reason to read this new book. In describing the book as “crystalline,” I am thinking especially of this story. Although Moore has mentioned this story briefly in at least two earlier books—this three-page account of the Lake St. Clair story is the defining version.

But, be careful. Now that Moore has told the story to me in these pages—as a writer who has worked most of my life among the Great Lakes, now I can’t stop thinking about it. That little story is both haunting—and hopeful.

Stories not only travel through time—they travel person to person and, once again, that’s a truth that defines the popularity of Moore’s work over the past three decades.

This Book Either Is—or Isn’t—Filled with Hope, Depending on Your Hopes

I told Moore in our Zoom that I found his book filled with hope. I told him I was going to use the word “hope” in my headline to this column.

He warned me against it.

“Hope is a confusing word,” he told me. “The word hope can be a problem, because people will think I’m talking about hoping for something, something they might want or some specific outcome. But when I talk about hope, I’m not interested in those things. I don’t know what the future holds. I don’t think that hope refers to a specific set of doctrines. But generally I would say that hope is an essential way of approaching life, as in the call to value ‘faith, hope and charity.’ If we are concerned about how to live in a community, today, I can’t think of a better trio follow than faith, hope and charity. But don’t let people think that I’m talking about hope for some object of desire.”

And so I have added Moore’s qualifier from his own lips.

Nevertheless, I am recommending this book as remarkably full of hope—a joyful collection of readings.

It’s true. That joy starts with Moore’s almost anarchic approach to his stories. He encourages readers to dive in anywhere, almost on any page. You could read the chapters in this book in reverse order, if you want, or select chapters at random. Each one is a crystalline artwork, and I use that word intentionally because Moore himself says he thinks of this book as an “artwork.”

Plus, this book is so easy to read! While many of Moore’s books are written for specific audiences—sometimes aimed more at religious leaders, therapists and academics than ordinary readers—this book is for all of us. There’s something here for everyone to discover, day by day, and there’s no excuse that you don’t have the time. These chapters take just a few minutes.

And for all of that hopeful, joyous light Moore has given us—I’m as happy with this new Moore book as I’ve been since I first discovered Care of the Soul more than 30 years ago.