The White man does not understand America. He is too far removed from its formative processes. The roots of the tree of his life have not yet grasped the rock and the soil. … Men must be born and reborn to belong. Their bodies must be formed of the dust of their forefathers’ bones.

Chief Luther Standing Bear, Lakota

.

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

The book opens with a burial:

I am standing before a northern lake on a windswept point of land as a young Indian boy I know is lowered into the earth by his friends and family. It is a strange and lonely funeral—they all are in their own way. But this boy was a friend of mine, and his loss has struck me with unusual force.

But, this is not a sad book.

It’s an honest book by a master of Native American narratives. Kent Nerburn always introduces himself as not Native American. But, through many decades of work and friendship with Indians in northern Minnesota, he has been welcomed as a Euro-American guide into Native communities. That relationship was sealed with the 1995 publication of the classic Neither Wolf Nor Dog, which now is recommended by many Indian leaders nationwide. Literary critics rank Kent with the likes of Anne Lamott and Annie Dillard for his talents with creative non-fiction.

Honesty is a key value for Kent, which was first expressed in his early career as a sculptor. His doctorate degree was in religion and art, so the universal quest for Truth (with a capital T) lies at the core of his vocation. That’s why this opening scene of a burial is far more than mourning a death. In fact, in Kent’s world, death is a natural part of every life. This grave-side scene is an invitation to travel with him through more than 140 pages of stories from Indian lands.

And therein lies the key to that opening scene: A body is literally returning to the earth in a natural cycle. There’s no more powerful evocation of the wellsprings of Indian spirituality than this little drama from the end of a young man’s life. As this opening story unfolds, Kent reminds us again and again: This is Indian land. And both words “Indian” and “land” are equally important. As in this brief, haunting passage:

This is Indian land. Its marshy surfaces and low-lying, scrubby cover make it rich in bounty for those who hunted and gathered as a way of life. And its rocky resistance to tilling has kept the full force of white settlement away. Even now the reservations surround the towns and serve as ghostly reminders that we who have come from other shores are still but visitors here, understanding only dimly the ways of the land that we have appeared to conquer. In the Indians who have made their home here—like my young departed friend—something lives that invests this harsh land with spiritual value. It is not some romantic taproot into primeval forest mysteries and pre-Adamic unities with nature. It is far more integrated, far more resolved and inseparable from their character.

Are you intrigued?

If you have loved Kent’s earlier books—or if you are discovering Kent Nerburn for the first time in this column—I can guarantee you won’t find a more thoughtful guide than Kent to lead you into these realms.

QUEST FOR A TRUE NORTH AMERICAN THEOLOGY

For a moment, let’s step aside from our conversation with Kent, this week, to think about why his work is so unique and valuable for all of us—in this continental land mass that we all should care about but have largely ignored.

As an American journalist covering trends in religion for more than 40 years, one of the most elusive spiritual values across this continent has been the quest for a true North American Theology. That’s because the conversation has been dominated by Christians who use the phrase to refer to “the state of our theology in North America.” Evangelicals, for example, focus on how Reformation roots in Europe 500 years ago have been transformed through churches transplanting those ideas in this New World landscape. (If you care to read more about this, we can recommend historian Mark Noll’s 2001 book, The Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American Christianity.)

Meanwhile, Catholic encounters with American peoples also stretch back half a millennium with as many crimes as successes in this cross-cultural collision. Only in recent decades have Catholic leaders grappled with these deeper questions—often in fits and starts and usually from a Euro-immigrant perspective. For example, by the early 1980s, the phrase “North American theology” was focused on whether Marxist ideas and Southern Hemisphere “liberation theology” could grow in the wealthier Northern Hemisphere. That debate seemed to leapfrog past what indigenous voices had to say about the deeper issues.

Then Pope John Paul II made a series of historic visits to Native Peoples in 1984 and especially in 1987, a tour of North America that I covered for Knight-Ridder newspapers. Around that time, John Paul startled many Catholic leaders by reopening the church’s relationship with indigenous cultures. Suddenly, the church began welcoming traditional Indian spiritual symbols and rituals, including sacred pipes, medicine wheels, sweat lodges, eagle feathers, drums and dance. Many Catholics didn’t like those changes; many Indians objected to this appropriation of their sacred traditions. However, decades later, a study by Catholic leaders found that 51 dioceses with Native members regularly use the Indian rituals welcomed in the ’80s.

To this day, John Paul’s talks to native peoples in the U.S. and Canada are cited as foundational documents. This includes John Paul’s response after he sat listening to Indian leaders speak in Phoenix before 16,000 Indians who had gathered to meet with him in 1987. He said, in part:

As your representatives spoke, I traced in my heart the history of your tribes and nations. I was able to see you as the noble descendants of countless generations of inhabitants of this land, whose ways were marked by great respect for the natural resources of land and rivers, of forest and plain and desert. Here your forefathers cherished and sought to pass on to each new generation their customs and traditions, their history and way of life. Here they worshipped the Creator and thanked him for his gifts. In contact with the forces of nature they learned the value of prayer, of silence and fasting, of patience and courage in the face of pain and disappointment.

Since that time, there have been fresh initiatives and voices rising coast to coast. Here’s one example close to our home base: In Michigan in 2007, the same year ReadTheSpirit magazine was founded, Lynn Hubbard and George Cairns launched an effort to explore North American Theology with Native Americans. Themes from that groundbreaking work continued as Lynn migrated Southwest and eventually wound up in California.

Indian voices also have become far more prominent. One example: Professor George Tinker, an Osage theologian and educator, is widely known for exploring the tensions and possibilities in the collision of cultures.

Other Native voices remain critical of the whole endeavor. Sherman Alexie, a best-selling author and co-creator of popular films like Smoke Signals, raises provocative questions for both Indian and Christian communities. Alexie keeps asking in many pointed ways: Who controls the traditions? Who controls the narrative now?

Trying to climb on top of that turbulent national conversation are a host of other pop-culture opportunists trying to market forms of Native American culture—or what Kent Nerburn dismisses as: “Junk peddled by people who are only concerned with making a buck.”

The landscape is littered. The conversation is confused.

What is sorely needed across our continent are clear-eyed visionaries and voices who can re-open the spiritual vistas of North American Theology and welcome all of us—Native and immigrant Americans—to rethink the spiritual possibilities we share as inhabitants of this land. And that, quite simply, is the deeper value of Kent Nerburn’s Native Echoes.

‘A LITURGY OF THE LAND’

This truth about Native Echoes will make the most sense to Kent’s fans who are familiar with some of his earlier books: In our interview about this new volume, Kent described it as “a confusing book that poured out of me and mainly I just had to be faithful to get it all down on the page.”

If you’re a fan, you recognize this bit of honesty as classic Kent.

And here’s another truth: The text of this brand-new volume was written more than 20 years ago in the mid 1990s, when Kent had finished a major oral history project with the Red Lake Ojibwe and his classic Neither Wolf Nor Dog also was pouring out of him. Unlike that best-selling book, which describes Kent’s friendship with the now near-legendary elder “Dan,” this book of two dozen stories and meditations eventually fell out of print. Kent could see the unique value in this book—it is essentially a companion volume to Neither Wolf Nor Dog—so, Kent decided to republish it himself as Native Echoes.

In the Indian tradition of the spiritual “Trickster,” however, this book’s rich meaning continues to flip top-to-bottom and inside-out as Kent reads, re-reads and re-re-reads its text.

“I think I got the title wrong, again,” Kent admitted to me. “When it was originally published in 1996, it was called A Haunting Reverence, and I never thought that was the right title.”

He said, “From the beginning, I saw this as a book about spiritual geography. At the point I wrote this, I had finished my doctorate and was still very conversant with my awareness of theology. I had just been working with the Native community and was exploring their spirituality and ways of thinking. There were so many forces that came together in that time and place. We were located right near the Continental Divide there. The best way I can describe it is to say: The land was inhabiting us. All of these forces came together and I had this explosion of revelation, fueled by what I was discovering there along with my own religious and scholarly background. This book is stories and meditations and scenes from life in that community—and what amounts to prayers, too.”

He paused. “I should have called it A Liturgy of the Land.”

Of course, in the 2018 publishing industry, producing a book about Native Americans without any “key words” signaling that readers would find Indians or “Natives” in the book is regarded as a mistake. What’s more? “I’ve been told that nobody would buy a book with the word ‘liturgy’ in the title,” Kent said, chuckling. “Isn’t that crazy?”

It certainly is. Properly understood, “liturgy” is simply, as Wikipedia puts it, “a communal response to and participation in the sacred.” The original Greek literally means “work for the people” or “public service.” Most readers, to the extent they even recognize the term, tend to think of it as a book of formal prayers, a term most common to Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians.

But in that original, ancient meaning, Kent truly is performing liturgy—a work for the people—as he crisscrosses Indian lands and invites us to come along, just as he does in his best-selling books.

So, let’s close this column by returning to that young man who is buried in the book’s opening scene. Are you wondering why he died so “young”? That’s because, Kent explains, the young man was deeply troubled, torn between the enticements of Euro-American culture and the voices of Indian elders. In one heart-wrenching scene, Kent describes the young man falling asleep as he sat with some young friends during such a talk by an elder:

The young people fidgeted and stared. They whispered to each other. The old man was going on too long. Like an animal going back into the forest, he closed his eyes, turned inward and was gone.

Why did he die? The honest answer is: This young man could not resolve the tension between the two worlds pulling at him.

And then Kent describes the deeper purpose of this book:

We have on this land a clash of genius. The European, logical heir to the Greeks, the Romans, the Christian in all its forms, brought to these shores a faith in progress, a teleology of hope. It is a fine and noble instinct, too quickly denigrated these days, that finds truth in movement, in discovery, in examination, in a promise of perfectibility. It is the motive force of evolution, the engine of exploration, the philosophical extrapolation of the way we experience time.

Yet there are other ways. The cyclical, the circular, the great gyre of repetitive ritual is also written in the earth in which we live. The planets, wheeling through time, the seasons, repeating their eternal liturgy, speak of a past that is almost alive in the present, and an earth revealed by ever more accute understanding of analogy. The mandala and the medicine wheel, as surely as the quest for the grail, reveal a path of spiritual understanding.

My young friend was caught in between. His progress had been too slow; his fatih in the eternal lessons of nature too weak a balm. He had lived his life suspended between the truths, and in the end, neither had been strong enough to save him.

Want Truth? This is quite simply A Liturgy of the Land.

From the original Greek: What a good work Kent Nerburn did for all of us in first publishing this volume! What a good work he is doing in bringing it back to us more than 20 years later!

What a liturgy he performs for us between these two covers!

.

Care to read more?

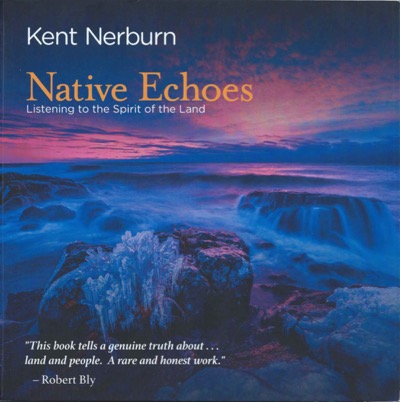

ORDER NATIVE ECHOES from Amazon in paperback—or, if you prefer, it’s also available for Kindle.

HEAR MORE FROM KENT HIMSELF in our earlier Q-and-A-format cover story with Kent about his Neither Wolf nor Dog trilogy

VISIT OUR BOOKSTORE—You’ll find lots of books that are great for small-group discussion in our own ReadTheSpiritBookstore and our new Front Edge Publishing Bookstore. That includes a Native American memoir, Dancing My Dream, by Warren Petoskey.