Kelley and her husband Claude with the community in Burundi. Click this image to visit Kelley’s site and learn more about her work.

.

“You can choose your friends but you sho’ can’t choose your family.”

Jem in To Kill a Mockingbird, 1960

By DAVID CRUMM

ReadTheSpirit Editor

Ever since Harper Lee wrote that line more than half a century ago, her words have circled the globe like holy writ. In South Africa, Archbishop Desmond Tutu has tried to soften the more troubling implications by adding, “You don’t choose your family. They are God’s gift to you, as you are to them.” Yet, to this day, the adage often fuels isolation, fosters lingering pain, taps into ancient tribalism and can fuel tragic competition.

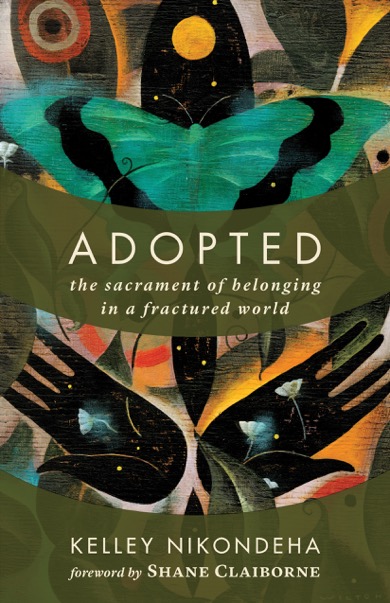

That’s why Kelley Nikondeha’s message is so radical—and timely in today’s splintering world. In her new book, Adopted: The Sacrament of Belonging in a Fractured World, Kelley proclaims:

We can choose our families!

“The idea is so simple,” Kelley said in an interview. “We can choose to be family. Yes, it is radical to say those words: We can choose to be family. And, it is true. We can choose to show up every day and become family. For us, we see this most visibly in our development work in Burundi. It is so clear to us in the unity we share in the big work of this small community, filled with hope as we see the forward motion of this community. We do not live solitary lives. It is in fully experiencing the communal aspects of life together that we begin to experience the family God is calling us all to become.”

Chances are that the ReadTheSpirit community is hearing about Kelley, Claude and their work in Burundi for the first time. So, let’s pause here to share some helpful links:

- Get her book: Here is the Amazon link.

- Visit Kelley’s home page: Here is her website and, yes, that is a silhouette of Jerusalem’s skyline in the center of her front page along with her personal affirmation: A Practical Theologian Hungry for the New City. And, yes, she is talking about the vision of one day living in a re-united kingdom of God—a vision shared by all of the Abrahamic faiths in various forms and terms. In her book, she writes specifically about the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, or “repairing the world,” as well as Christian and Muslim visions of a united world.

- Enjoy her columns: About once a month, Kelley posts a new column. Her January 2018 reflection was written during a recent trip to Burundi. Kelley also contributes to She Loves Magazine and this particular January column contains a link that will carry you to that website, as well.

-

Discover Communities of Hope: The Batwa community in Burundi, which Kelley and Claude Nikondeha helped to organize over the past decade, tells its story across a number of websites and social media pages, including Facebook. Perhaps the best summary of the Nikondehas’ efforts is their column on the Communities of Hope website. (You’ll find that column by clicking on this link, then clicking on the photo of Kelley and Claude at the top of that page.) Kelley begins that column with these words: “If you wanted to create a compelling community development project with the best chance of success, I don’t imagine this one would have met any of the classic criteria.”

An Unlikely Visionary

That same line might also describe Kelley’s unlikely origins. As she explains in the opening pages of her book, she was given up by her mother as an infant, cared for by an adoption agency in Los Angeles and soon was claimed by a woman unable to have children.

As she tells us in the course of the book, her story has biblical parallels and led her into a lifetime of ever-widening circles of awareness about God’s creativity in our world. She now welcomes and encourages visionary leaps. For example, she was raised Catholic and considers this her “mother Church,” even though her master of divinity was earned at Fuller Theological Seminary, an evangelical school. On her website, she tells visitors: “I’m a woman continually recalibrated by the liberation stories of Miriam and Moses, the intoxicating poetry of Isaiah and the provocative parables of Jesus.”

That line also is a pretty good description of the biblical reflections woven into her new book-length memoir, Adopted. While it’s natural for a Christian theologian to write and teach about Jesus, the strong focus on Hebrew scriptures in Kelley’s work is striking. In our interview, she said, “I am deeply influenced by Isaiah. If I had to carry with me just one book of the Bible to nourish my imagination, it would be the poetry of Isaiah and the vision of the new city.

“That’s such a compelling vision in our world today,” she continued. “We envision, and we work toward, a city that thinks differently about how to include people, a city that cares for the health of all the people, an economy that is calibrated to make every family strong. That’s the vision that inspires me as a person of faith and certainly it guides our aspirations as development partners with the people in Burundi. Those are visions to work toward every day. Each morning, I ask myself: How are we moving one step closer to that vision? How can we help to construct this new community based on God’s justice?”

A Child Shall Lead

What makes Adopted so compelling is that Kelley grounds her soaring spiritual reflections in a series of real-life stories about her own childhood and the childhood of her two children, adopted from Burundi. One of her first stories involves a moment all adoptive parents experience, when their children begin to think about their birth parents and often construct heart-felt images of who these parents might be.

One morning, Kelley finds her little son weeping, emotionally overwhelmed with an image of his birth mother in Africa needing food to survive. When Kelley comes to comfort him, he tells her, “I love you, but I have to go to her.”

This is impossible because the Nikondehas have no way of reaching the parents of either of their children. They adopted their son because he was living in a group home with no record of his parents. They adopted their daughter after both of her parents died of AIDS. (The story of that adoption and the anxiety over whether the little girl also had AIDS is one of the most compelling sections of the book.)

All of these experiences with her own children move Kelley to rethink her own adoption many years ago and even to change her own perspective on adoption. As a very young woman, she thought she was an expert on the subject, yet her longer life’s story tugs at those early assumptions into an ever-expanding network of awareness.

In her book, she writes: “This is how adoption works—like a sacrament, that visible sign of an inner grace. It’s a thin place where we see that we are different and yet not entirely foreign to one another. We are relatives not by blood, but by mystery. All that divides us as nations, ethnicities, and religious traditions is like a vapor quickly extinguished in light of our adoption into God’s family.”

As she leads us in these pages through her own meditations on classic Bible stories, she invites us into this greater mystery of adoption—hopefully with new enlightenment awaiting us as we read. In fact, the Christian New Testament argues passionately, through the letters of Paul, that we all are adopted by God, Kelley writes.

“The stories of scripture lead us to understand our belonging to God’s family through adoption, full heirs to our Father’s world. As heirs, we participate in extending God’s Kingdom of peace. As family, we recognize others as siblings who ought to be treated as such. As adopted ones, we extend that magnanimous belonging to others.”

She continues, “True belonging has never been limited to physical means or markers. Through each new generation, God has shown us that family membership is inclusive, generous and diverse. Each new story stretches our imagination and challenges our capacity to embrace others as family. Adoption points to an ever-extending family that crosses boundaries of all sorts, excluding no one.”

How We Know This Works

One of the most inspiring narrative threads in Kelley’s book are the experiences she shares from her work with her husband in helping to establish a village for the typically shunned Batwa minority. In the book, she explains: “Burundi is a country comprised of three tribes, the majority Hutu, the traditionally significant Tutsi, and the maligned Batwa. Small in stature, in number, and in local esteem, the Batwa live undocumented on the edges of Burundian society. The first time Claude met someone from this tribe was in 2004.”

That was such a startling experience that it transformed Claude’s life! He thought of himself as a proud Burundian, yet he had never even met a member of the Batwa tribe until well into his adulthood. This led to a strong commitment by both of the Nikondehas to repair this historic breach in cultures. It also led to confusion in their own family.

Kelley put it this way in the interview, “My husband’s own family was confused by his interest in these people. If he was going to help someone, why not help their clan? Why not help his own family? Why help this other clan? How could he think of the Batwa as family?”

In the book, she writes: “Here is what Claude knows deeper than words: All Burundians are his relatives. He stands in soldarity with these families, be they Batwa, Hutu or Tutsi. He pours out his life for them because they are irrevocably his own. Once he told me that his very humanity depended on how he loved these families. As an adopted one of God, he knows, like Jesus, like Paul, there is no basis for division along clan or ethnic lines.”

Voices Converging

In 2018, Kelley is not alone in making this radical appeal.

In a moving foreword to Kelley’s book, evangelical activist Shane Claiborne writes, in part:

“Mother Teresa once said that the circle we draw around family is too small. We put limits on love. Because our vision isn’t as big as God’s, we can end up spiritually short-sighted. We reduce family to biology or nationality or ethnicity. We put up picket fences and build walls along our borders. We use the language of ‘us’ and ‘them,’ and we draw lines in the sand. Kelley Nikondeha is the perfect person to set us free from our myopia and tunnel vision. She helps open our eyes to the boundless love of God. This book is about belonging. It is about the limitless hospitality of God, which has the power to transform us into people who extend the same hospitality to others.”

But, this is far more than speculative theology. This is a movement in popular culture and in science as well.

One of the mostly highly praised—and most popular—prime time TV series, This Is Us, explores issues related to adoption in almost every episode. The series makes little reference to religion. And that dramatic series’ popularity is despite the widespread rise of nationalist and racist voices in American culture over the past year.

One of the hottest Christmas gifts in recent years is DNA testing. So many millions have purchased the service that companies doing the analysis experience long delays. And, while genealogy may seem to be the ultimate obsession of a family-focused, isolationist movement away from the global community—the fact is that these DNA reports reveal vast global connections between communities. A typical DNA report from the popular Ancestry.com also reveals links to a long list of far-flung, distant relatives. The overall movement is toward global connection, not away from it.

One of the most eloquent voices calling for a merger of faith and family on a vast global scale is a scientific secularist: James Gustave Speth. For many years, Speth has been on the cutting edge of environmental issues around the world. In his book, The Bridge at the Edge of the World, Speth explores evolutionary instincts that might help humans survive the environmental catastrophes yet to come. He explains that adaptation and self preservation makes sense in evolutionary theory for individuals, families and communities. But that instinct breaks down on a worldwide scale. Is there any force, any compelling vision, that might motivate all of humanity to gather in unified action?

Speth answers that question, toward the end of the book, by exploring several possible solutions, including:

“Another way forward to a new consciousness should lie in the world’s religions. … The potential is enormous. About 85 percent of the world’s people belong to one of the ten thousand or so religions, and about two-thirds of the global population is Christian, Muslim or Hindu. Religions played key roles in ending slavery, in the civil rights movement, and in overcoming apartheid in South Africa, and they are now turning their attention with increasing strength to the environment.”

‘The Carry-Away Piece’

Toward the end of our interview, Kelley repeated again: “We can choose to be family.”

She paused, then said, “That’s the carry-away piece from this book. Remember: We can choose to be family. And as we decide to make that choice, we can express it in many different ways. Actual adoption of a child is one very powerful way, but this choice to be family can take so many forms! It can create new communities. It can transform broken communities.

“And, it’s a truth right there in our shared traditions—Christians, Muslims, Jews. That’s the power of belonging. When we use the word family in this way, we are calling on a deep fidelity to the truth that in the long term, we belong to one another.”

She closes her book with a similar affirmation, writing:

“War, death and disease rend the world. Injustice tears at the fabric of neighborhoods, making relinquishment the best but most heart-wrenching choice under bad circumstances and leaving behind orphans, families at risk, people side-lined with no support system or sign of hope. Adoption is one way we dare to stitch the world back together. It offers a needle and thread to begin the mending. We cannot mend all the wounds, gather all the fragments scattered about war zones and orphanages and underserved neighborhoods—but we can do what we can with each stitch.”

Care to read more?

For more than a decade, ReadTheSpirit has encouraged the publication of books that help to stitch the world back together again. In addition to ordering a copy of Kelley’s book, please look over the books we are sending into the world.