‘BIG BREATH’ and ‘THREE BREATHS AND BEGIN’

.

Story By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

The moment I read this paragraph, I wanted to talk to high school teacher William Meyer—because I am certain that our readers will find this very good news. In his new book, Three Breaths and Begin—A Meditation Guide in the Classroom, Meyer writes:

Since 2012 I have introduced meditation to my classroom as a tool to deal with the growing stresses of the school day, but also as a lens by which to facilitate greater connection between the students and the curriculum. What started out as part of a student research experiment involving a small group of six students sitting in the corner of a science classroom has grown into a club, a common occurrence in my classroom, and now an integral part of the community. As a result of the growth of this practice in the school over the years, students can be found meditating before tests, performances, speeches, sports games and even assemblies. The meditation bug has not only bitten the students, but it has also caught the attention of the administration, faculty, and community. It has become incorporated into weekly department meetings and has become a part of professional development workshops, book studies, and even faculty wellness programs of the school. The parents have been equally enthusiastic, embracing meditation in the form of a weekly Thursday evening circle.

Are you as surprised as I was by what Meyer has achieved throughout his high school? He teaches at Bronxville High School in Westchester County north of New York City. In seven years of developing what is now a very popular practice among students and staff—and extending it into a public invitation to the community on Thursday nights—Meyer has not encountered one angry parent. That’s what he writes in his book; and that’s what he told me in our interview this week. I will admit that, as a journalist who has covered religious diversity for 40 years, I was surprised to hear this.

Of course, it helps with community-wide acceptance that some of the past leaders of his student meditation club wound up going on to top Ivy League schools—and these students credit meditation as one of the practices that boosted their academic abilities.

Aren’t you eager to find out how Meyer has developed this program? Now, thanks to New World Library, two books bring Meyer’s guidance on meditation to the world. Three Breaths and Begin is a 256-page overview of his approach to meditation and mindfulness, especially geared toward teachers who want to bring these ideas into their classrooms. Then—although Meyer teaches high school students—he also has published a brief, beautifully illustrated introduction to meditation for children, Big Breath—A Guided Meditation for Kids.

In addition, he has an information-packed website with links to lots more news-media coverage of his work. If you dig a little deeper into that website, you’ll find a section with contact details and links to his schedule as he occasionally travels to teach and consult.

With the publication of Meyers’ two new books, I expect his travel schedule for the coming year will quickly fill to capacity. So, if you are discovering his work today through this column, and you might want to invite him into your community or upcoming conference—then, you will want to act quickly.

MYTH BUSTING:

THE POPULARITY OF MEDITATION

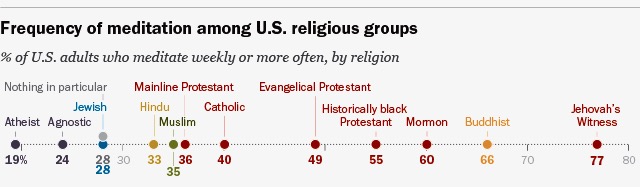

In my interview with Meyer this week, I asked him about a Pew Research report on how widely meditation has been accepted across the American landscape. He had not spotted this particular Pew report, so I asked him several questions about the data.

I began by telling him, “First of all, here’s the headline news: Pew’s conclusion—drawing on their in-depth Religious Landscape Study—is that meditation is very popular these days. I think that’s one reason you have been so successful in winning over your community. Millions of Americans regularly meditate. Overall, Pew reports that 40 percent of Americans meditate at least weekly. You’re a Catholic yourself. Does that level of meditation surprise you?”

“Not at all,” he said. “My dissertation work includes Thomas Merton and his connections with meditation, so I’m very familiar with this practice among Catholics.”

I said, “When Pew divides up the data by religious groups, Catholics are exactly at 40 percent—the same as the overall population. So, now, let me ask you about a couple of other groups. You haven’t seen this chart yet, but would you guess that ‘evangelical Protestants,’ as a group, meditate more or less than the average 40 percent?”

“Less,” he said.

“No, actually, a higher percentage—49 percent,” I said. “Clearly the concept and terminology of ‘meditation’ has changed quite a bit over the decades. I think this is another reason you’re finding such a wide-open acceptance. Millions of Americans are quite comfortable using the term. So, what about members of black churches? More or less than 40 percent?”

“Less again?” he asked in response.

“Nope. Even higher—55 percent meditate at least weekly,” I said.

Of course, traditional approaches to meditation around the world do vary. A Zen approach to meditation might be closer to “clearing out minds,” while Christian contemplation might be described more like “deepening our focus” on a prayerful concern. The Pew researchers point out that people overall are using the word to describe quiet, personal reflections—even though their exact steps will differ, based on a person’s tradition.

However, the Pew researchers stress that meditation has never been foreign to Christianity. Meditative prayer goes back to the early centuries of Christianity, Pew points out: “Within Christianity, the practice of meditation or silent contemplation dates back to the Desert Fathers (early Christian monks and nuns who sought God in the quiet and solitude of the Egyptian wilderness) during the first centuries after the death of Jesus. Today Christians of various traditions still encourage meditation as a means to try to get closer to God.”

HOW WILLIAM MEYER DISTILLS MEDITATION

As we continued the interview, I said, “Having read both of your books—including this wonderful new children’s book—one thing that struck me is that you have distilled meditation down to its essentials in many ways. You don’t include elements that could raise community concerns. Let’s start with the fact that you’re not clergy, and you’re not trying to bring in an outside spiritual teacher to lead these sessions. And you’re not teaching someone’s religious doctrine.”

As we continued the interview, I said, “Having read both of your books—including this wonderful new children’s book—one thing that struck me is that you have distilled meditation down to its essentials in many ways. You don’t include elements that could raise community concerns. Let’s start with the fact that you’re not clergy, and you’re not trying to bring in an outside spiritual teacher to lead these sessions. And you’re not teaching someone’s religious doctrine.”

“That’s right. And, that’s a big factor in the acceptance. I’m just a high school teacher and we started all of this as a way for students to connect better with their studies,” he said. “It helps that the founder of our student meditation club went on to Harvard. Another leader of the club went on to Dartmouth. The word gets around that this really does help students.”

I continued: “I think there’s another factor. Given your looks, and the way you dress in the photos I’ve seen online, you seem more like a Fortune 500 vice president taking part in a corporate conference—rather than any kind of religious leader. There are no eccentric visual symbols or garb.”

He laughed, “Yeah, that’s true.”

“Plus, you don’t use music, or incense, or bells,” I said.

“That’s right,” he said. “We don’t need that stuff. I don’t have students bring in yoga mats and sit on the floor. We just make a circle of chairs and sit there. I usually turn down the lights. But that’s right. When I lead these guided meditations, I am stripping away many of the trappings that might raise people’s anxiety.

“And there’s nothing secretive about what we do,” he added. “We do the same kinds of things for the students, the faculty, the members of the community who come on Thursday evenings—and I’ve published the texts of some of my guided meditations in Three Breaths and Begin. I’m taking the mystery out of what we do—what millions of Americans like to do every week, according to that Pew report.”

‘TAKE A BIG BREATH’

Both of Meyer’s books are as straight forward as his successful introduction of meditation has been in his community. Anyone who has visited a meditation group or has taken instruction in meditation will recognize his techniques. They start with relaxation and awareness of one’s own breathing.

The first meditation in the book for adults begins this way:

“Find a comfortable spot on a chair or cushion. Make any adjustments you might need, rotate your shoulders, relax your arms, and let your legs be loose. When you are ready, either lower your eyes into a soft forward gaze or, if you are comfortable doing so, close your eyes.

“Now take three breaths and begin.

“Feel yourself breathing in and breathing out. Feel the space around you and within you.” (And the text for this guided meditation continues from that point.)

The children’s book begins this way:

“Find a comfy spot.” (A cute little girl is shown hugging a big, fluffy, red blanket.)

“Maybe on a squishy cushion or a soft blanket.” (A different child arranges some pillows.)

“Let your arms be long and your hands be soft. Place one palm in the other and gently squeeze your hands together. Take a BIG BREATH and close your eyes.” (A third child sits in a meditative posture.)

“Can you hear your breath? Can you feel it? What does it sound like?” (Now, the illustrations open up to evoke an abstract blue swirl of sky and water behind this seated child as the process expands awareness.)

WHY THIS MATTERS

These practices work. They have worked for thousands of years to improve mindfulness, attention to work, compassion toward others and a general sense of wellbeing.

But bringing these practices into a public school can be tricky, Meyer admits.

“How we carefully introduce these practices is important, because as educators we all know that it only takes one really angry parent to rise up and scare school administrators,” he said.

“What I’m sharing in these books is our story of how much difference this has made in so many lives—students, teachers and members of the community. I know that we are fortunate to have the whole community really embracing what we’re doing. The good news is: I know this is possible—we’ve done it here.”

.

Care to Read More?

William Meyer’s work involves offering students tools to develop what educators often refer to as their social-emotional resources. Our publishing house has worked extensively with educators on these issues, including in early childhood—the audience for Meyers’ colorful book Big Breath.

Funding cuts and shifting public priorities nationwide mean it’s more important than ever to get involved in your local community. Front Edge Publishing partnered with United Way to produce a book series highlighting six nonprofits that work tirelessly to improve early childhood education. In order to help you facilitate early learning in your own community, we’re also offering free discussion guides for the books in this series.