EVEN AS Gen. Robert E. Lee was surrendering at Appomattox on April 9, 1865: Recently freed Black residents of Charleston, South Carolina, risked their lives to publicly prepare for the first Decoration or Memorial Day by digging up a mass grave of Union soldiers left by the defeated Confederate army. These Black volunteers then prepared proper graves for each of those more than 250 Union soldiers who died due to starvation and disease in a Confederate prison camp inside a local horse-race course. This photograph (above) was taken while the new graves were being prepared. Later, those Black volunteers built a decorative fence around the new cemetery, including an archway proclaiming this hallowed ground dedicated to the “Martyrs of the Race Course.” On May 1, 1865, these Black families held a parade of more than 10,000 people to this site to memorialize the dead with flowers, preaching, readings from the Bible and hymns—followed by family picnics. (Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

‘This was the first Memorial Day.’

.

FORT SUMPTER APRIL 14, 1865—

AND NOW MONDAY, MAY 30—Given the racial trauma that continues to roil our American landscape, we believe it is important to cover Pulitzer-Prize-winning Yale historian David Blight‘s ongoing campaign to correct our history books and give credit to newly freed African Americans for establishing our post-Civil War tradition known to us now as Memorial Day.

“African Americans invented Memorial Day in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1865,” Blight says in a lecture, an excerpt of which you can view below via YouTube. “There are cities in the United States North and South that claim to be the site of the first Memorial Day, but they were in 1866—they were too late. (As a researcher,) I had the great blind good fortune to discover this story in a messy totally disorganized collection of veterans papers at a library at Harvard some years back.”

Blight continues, “What you have there is Charleston in 1865 is African Americans, recently freed from slavery, announcing to the world with their flowers and their feet and their songs what the war had been about: What they basically were creating was the Independence Day of a second American Revolution. That story got lost for more than a century.”

One of Blight’s early steps in his campaign to correct our history books was an OpEd essay in The New York Times, which now has become an oft-quoted summary of these events. The essay says, in part:

For the earliest and most remarkable Memorial Day, we must return to where the war began. By the spring of 1865, after a long siege and prolonged bombardment, the beautiful port city of Charleston, S.C., lay in ruin and occupied by Union troops. … Whites had largely abandoned the city, but thousands of blacks, mostly former slaves, had remained, and they conducted a series of commemorations to declare their sense of the meaning of the war. The largest of these events … took place on May 1, 1865. During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the city’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club into an outdoor prison. Union captives were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand. After the Confederate evacuation of Charleston black workmen went to the site, reburied the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. .. The symbolic power of this Low Country planter aristocracy’s bastion was not lost on the freed people, who then, in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged a parade of 10,000 on the track. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

Blight also has written about this milestone on his own website, including this passage:

Following the solemn dedication the crowd dispersed into the infield and did what many of us do on Memorial Day: they enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches, and watched soldiers drill. Among the full brigade of Union infantry participating was the famous 54th Massachusetts and the 34th and 104th U.S. Colored Troops, who performed a special double-columned march around the gravesite. The war was over, and Decoration Day had been founded by African Americans in a ritual of remembrance and consecration. The war, they had boldly announced, had been all about the triumph of their emancipation over a slaveholders’ republic, and not about state rights, defense of home, nor merely soldiers’ valor and sacrifice.

As a result of Blight’s campaign, now, the public historical record is changing. The widely used HISTORY channel website, for example, posted this in 2019 and updated it in May 2022:

His efforts have expanded over the years to include historical reflections on the way this annual observance reflects the meaning of American freedom and diversity in other parts of the U.S. In 2017, Blight was invited to write for The Atlantic magazine. He chose to focus this Atlantic story on memorial traditions in New Orleans, headlined:

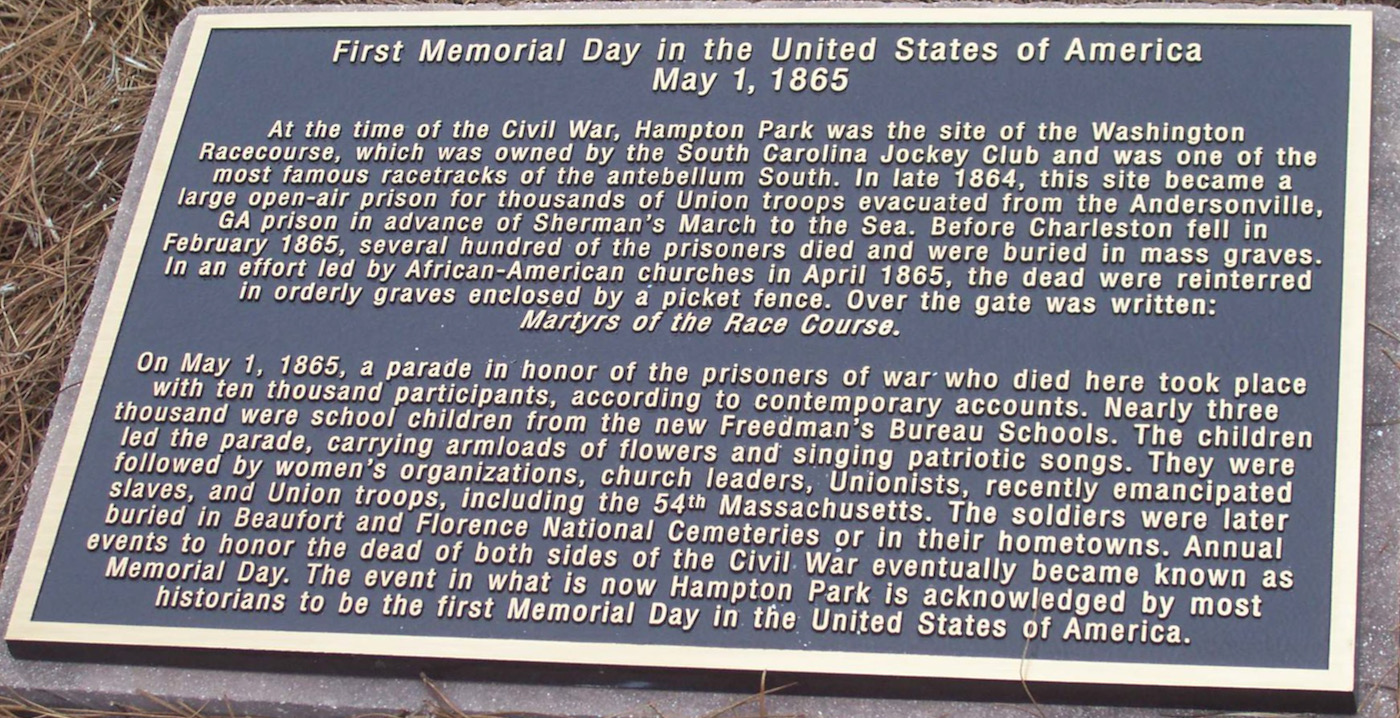

Over the years, as a result of Blight’s work, various new historical markers have been posted in Charleston.

SECURING THE HISTORY IN CHARLESTON—For more than a century, Confederate sympathizers in South Carolina actively suppressed the history of the ground-breaking 1865 event—despite the fact that it was covered by newspapers at the time and was documented in at least a few photographs held by the Library of Congress. The Confederate sympathizers were so effective in their efforts that this crucial American memory was effectively erased for more than a century. Today, permanent memorial markers are a public record of the event. (Click on the photograph to enlarge it for easier reading.)

.

Care to hear Yale’s Dr. David Blight tell the story?

The video quality of the following YouTube clip is not ideal, but the audio is clear. In this seven-minute summary, Dr. David Blight mentions other related events held in Charleston, including a gathering at Fort Sumpter. The Library of Congress also holds original photographs taken at the April 14, 1865, Fort Sumpter memorial, including this photograph and also this photograph that originally were printed for viewing in a stereopticon.

.

.

.

.

Tell Us What You Think