“One hundred years ago, there was a poor nine-year-old Black girl in rural Mississippi, an orphan, fixing to turn 10 come summer. Could she possibly have imagined that she would someday have a biographer (in a manner of speaking) from a prominent white Southern Family who now lives in a gleaming high-rise with a view of the Gulf of Mexico?”

So begins a recent post on Golf.com. And so begins the inspiration for “Playing Through,” a movie written by a novice and mostly filmed two years ago at Laurel Oak Golf Community. The filming process intrigued me and my fellow (make that: sister) LOGC golfers in Sarasota.

The orphan cited by Golf.com was Gary, Indiana, resident Ann Gregory. In 1956 she became the first black woman golfer to play in a US Women’s Open and, at 44, in a US Women’s Amateur tournament. The story’s astonishing on two counts. The golf world was notoriously male dominated. It’s joked the term golf was an acronym for Gentlemen Only Ladies Forbidden. And, before Tiger Woods, the sport was overwhelmingly a Caucasian affair.

“Playing Through” premiered at Ringling College in Sarasota. I was lucky to attend that premiere with some golf buddies. We had fun figuring out which scene was shot on which hole.

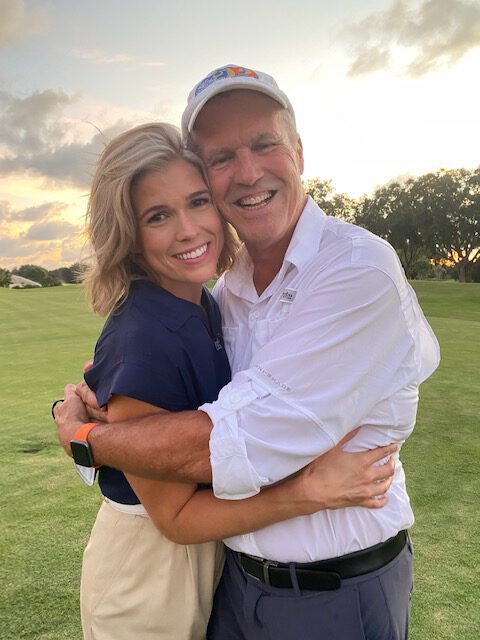

At the premiere, I met producer Curtis Jordan and followed up with a conversation.

For 30 years Curtis coached rowing at Princeton U. He also coached several Olympics rowing teams. His mother, Josephine Knowlton Jordan, had been a golfer as well as a harness-racing driver. Curtis knew she’d competed in a 1959 US Women’s Amateur at Congressional golf course, but she’d spoken little about the experience. In 1991, after Ann’s death, a friend forwarded a Sports Illustrated article mentioning African American golfer Ann Gregory as a pioneer in women’s golf. The article referenced a match she’d played against his mother.

The article “sparked my imagination,” Curtis says. He began writing about the event “as an exercise.” In retirement, for about four years Curtis had “slowly, painfully” worked on a movie script. He mentioned it to a friend from Princeton. That friend’s son, Peter Odiorne, is a producer and director. His company, Unbounded Media, wanted to produce sports films with inspirational messages. Odiorne was in. His company took Curtis’ rough script and “structured” it.

Curtis and Peter spent five months looking for two lead actresses. Those they wanted weren’t available at the same time. “We knew this would be a low budget film,” Curtis says, “but we still weren’t sure how to pay for it.” They changed their approach and started looking for women who could play golf, act and had a social media presence.

On Instagram, they found Andia Winslow, a black woman who played golf and was a voice over actress. They were “relieved” when Andia, with no on-screen experience, proved comfortable on camera.

As for the fictional Babs Whatling character, Peter had previously worked with TV actress Julia Ray. He knew she played golf.

“We didn’t have a lot of money or time,” Curtis says. “But Andia and Babs turned out to work well together. They put in long days and adapted on the fly and were invested in each other’s success.”

Curtis says the film represents “a collaboration of the Sarasota community.” That collaboration included Ringling College, which provided tech facilities and student labor. It included the West Coast Black Theatre Troupe, which brought in cast members including founder Nate Jacobs. It included the Sarasota Opera which provided housing. And local residents. LOCC members Audrey Robbins and Harry Leopold, hearing about the project, introduced Curtis to Larry Thompson, the dynamic president of Ringling College. The Leopolds also arranged for the filmmakers to have access to Laurel Oak’s two golf courses for ten days.

“The whole community can feel proud,” Curtis says.

Ringling College had built a state-of-the-art film production department with two sound stages and pre and post operations, hoping to attract commercial business. But tax laws in Florida changed, restricting Ringling’s ability to affect commercial collaborations. During the pandemic, the facilities weren’t used. Ringling president Larry Thompson was delighted to cooperate. He deemed the experience his students received “as good as cash in their pockets.”

The film’s about 95% finished, Curtis says. The project has consumed the past five years of his life. What’s next? “I look forward to spending time with my wife and my dog and playing some golf.” But he considers the project “worth all the time, effort and expense.”

“Playing Through” was shown at the Sarasota Film Festival and has been accepted by film festivals in Montreal, Durban and Martha’s Vineyard. Curtis hopes others will include it as well.

The moral of the story: Never underestimate the power of a woman to play golf. Or of one man’s determination to tell an inspiring tale.