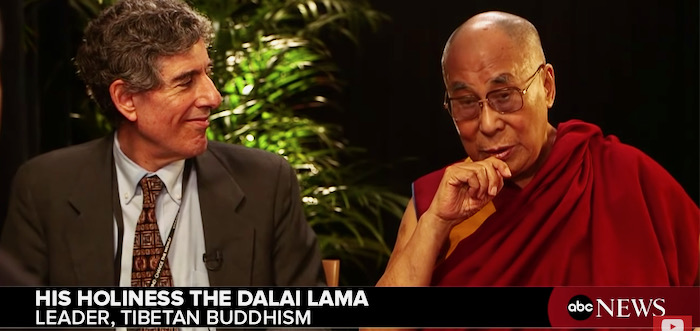

Ruth Petzold swims with a wild green seat turtle off Molasses Reef, NOAA Marine Sanctuary, Key Largo.

Ruthie Petzold, underwater photographer, is one of the most talented and resilient people I know.

Born in Grosse Pointe, MI, in “the last century” (1942), Ruthie received her first camera, a Brownie Hawkeye, at 7. “Instant love,” she says. “I spent all my allowance on film and processing.”

Ruthie’s parents instilled in their children “the self-confidence to do whatever we wanted and to be the best at it.” The family spent summers in Rye Beach, NH. Ruthie’s mom insisted Ruthie, her two sisters and brother learn to swim. At 2½, Ruthie was the youngest child to swim across the pool without water wings. She earned her Red Fish badge. When her mom sewed the badge to her bathing suit, that became the only suit she’d wear. Guided by a “fabulous” swimming coach, Charlie Adams, Ruthie became the New Hampshire state swimming and diving board champion at 12. She was “fascinated” by the sea stars and snails in Atlantic tidal pools. She also loved horses and became hunter/jumper club champion.

A car crash changed the life of this athletic whirlwind.

In 1958, Ruthie was a student at Sacred Heart boarding school in Conn. Family friends picked her up for a ski weekend in Vermont. In a blinding snowstorm, the car in which Ruthie rode crashed into a snowplow. Ruthie was thrown from the back seat into the front window. Due to the storm, the doctor who was called couldn’t drive. He hiked five miles to the accident scene. Ruthie’s sister, Anna, also injured, recalled an attendant with Elvis sideburns saying of herself, “No point in rushing. She’s lost so much blood she won’t make it.”

Both sisters survived. Ruthie suffered compound fractures of her tibia and fibula. She spent the next year in a full leg cast, with a plate and screws holding her leg together. A doctor told her father she’d never walk again. Ruthie was determined to prove him wrong. She’d seen a film in which an injured horse, slated to be put down, was instead run in sand to strengthen his broken leg. Though Ruthie’s ankle was destroyed, she walked in sand every chance she could.

Did she ever lament: Why me?

“Never. Everybody deals with something. I just decided to keep doing what I loved.” That included skiing, tennis and biking. Eight years later, a skiing accident in VT resulted in a comminuted, compound ankle fracture. Viewing her Xray, the doctor at Sugarbush stopped counting breaks at 20. Ruthie was wheeled into a phone booth to call her mom, person to person, long distance. “I have a little problem,” she said.

Ruthie being Ruthie, she was back to playing tennis as soon as she could. In 1968, a screw came loose in her ankle and “felt like a knife in my foot.” Heading into surgery, she asked her doctor to save the plate in her leg. Years later, she had an artist sculpt that plate into a decorative palm tree.

“I’ve had a leg issue since I was 16,” she says. “I’ve tried not to let it stop me.” Sipping her second glass of Chardonnay, she says, “I have a hollow leg now.”

Unable to ski any longer, Ruthie became certified in scuba diving. Whenever she visited her parents in Palm Beach, she dove “all day long” with garage mechanics and Navy frog men. There were few other women diving at the time. She planned to run her own chartered trip, but the boat sank.

Meanwhile, family friends had begun hiring her to photograph weddings for Detroit brand name (i.e. automotive) families. She became a successful portrait, event and fine art photographer.

Earning her pilot’s license, Ruthie teamed up with friend Elaine Harrison. In 1978, the twosome boarded Elaine’s single engine Cessna 206 for a madcap adventure of 10,000 miles through Central and South America.

On their first stop in Mexico, they buzzed a grass landing strip “to alert the dude with goggles and an ascot who was jogging down the runway.” They landed only be surrounded by Mexicans holding machine guns.” A white-haired gentleman greeted them, promising that his men would protect their plane. The men stood on each other’s shoulders to refuel the plane, bucket by bucket.

In Saiche, Guatemala, the site of old carved stone ruins, they stayed in a “falling down” inn along with a French spelunking team. When power was turned off at 9pm, they drank warm beer with the spelunkers.

In Nicaragua they were weathered in above a Chinese restaurant and brothel.

In Venezuela they hooked up with gold panners. They met a pilot who flew them to Angel Falls and banked the wing tip under a cascade of water. “My wildest ride ever,” she says. The pilot’s girlfriend, who came along, was so terrified she passed out.

Ruthie’s adventures had only begun.

The 1980s were “a whirlwind of diving.” In 1985, she visited Indonesia on a live-aboard dive trip and met Greg MacGillivray, then filming for Imax. (The American cinematographer would go on to receive two Academy Award nominations.) MacGillivray recommended Ruthie visit New Guinea. So off she went “totally unprepared” to meet members of the Dani people who wore nothing but gourds in strategic places.

In 1987, Ruthie circled the world twice. “It was easier to keep going around than to keep coming back.” Trips included whale watching and diving and research exploration. She visited the Asmat region of southwestern New Guinea, near the area where Michael Rockefeller had disappeared. When Ruthie arrived along with two guides, children ran and hid, but soon people warmed to their arrival and they enlisted six local rowers. The group trekked through the jungle and rode in dugout canoes for almost two weeks. Ruthie’s thermometer broke at 140 degrees. New Guinea is the second largest island in the world, she notes. Iceland’s the largest.

Ruthie took over 50 diving trips with “the Shark Lady,” famed underwater researcher Dr. Eugenie Clark. Eugenie was the founding director of Mote Marine, now a world class marine research center in Sarasota. Ruthie and Eugenie dove four to six times a day.

In 1990, a torn Achilles tendon prevented Ruthie from joining Eugenie’s trip. Three months later, despite a stiff ankle, Ruthie visited the Solomon Islands aboard the Billikiki. The dive boat held 12-14 guests and offered photography seminars. At the time, Ruthie took 300 rolls of film. She eventually switched to digital. Ruthie “fell in love” with the Solomon islands and has visited 11 times. .

Ankle replacement in 1999 left Ruthie depending on crutches for almost three years. Her left ankle became infected with Mersa. In 2000, nine different doctors recommended amputation below the knee. Ruthie’s mother was turning 90 that year. Ruthie finally agreed to the surgery. Her goal was to dance at her mother’s birthday. Two months and nine days later she reached her goal and danced.

Since then Ruthie has needed several prosthetics. “Flip,” her stump, keeps shrinking. Ruthie’s prosthetics come from the Arthur Finnieston Clinic which makes limbs for Para Olympians and where Ted Kennedy’s son, Ed Jr., was treated. After an earthquake in Haiti, the Finnieston clinic volunteered their services and fitted 50 patients a day. So many military vets are returning with lost limbs, Ruthie says, that prosthetics technology keeps improving.

Ruthie’s close to her cousin, renowned broadcast journalist Miles O’Brien, who lost an arm above the elbow from an injury. “When we’re together,” she says, “we’re quite the pair.” Ruthie recently met up with “OB” in Paris. OB’s friend, an ex-French Navy Seal whose uncle lives in a barge on the Seine, toured them through locks and under the Bastille. “Dark, exciting and unique,” Ruthie recalls.

Since 2004, Ruthie has been “incredibly lucky” to attend the Laulupidu in Estonia four times. The national songfest features over 30,000 voices under one director. “It’s like the skies have opened and angel choirs are singing.” She was introduced to the experience by her dear friend, Estonia-born Ivi Kimmel.

Ruthie’s praying her problems with Flip can be resolved. Having just turned 80 on Jan. 12, Ruthie wants to keep going, full speed ahead. The Solomon Islands still beckon.

“I’ve been lucky to see God’s creations most people never see. From microscopic organisms important to the food chain to endangered leafy seadragons in southern Australia to polar bears in Norway and Manitoba. My life’s been great, and it ain’t over yet.

“Life is for living—no matter what’s thrown at you. You can’t just make lemonade from lemons; you can make margaritas.”

Thanks, Ruthie, for sharing your escapades, your art and your indomitable spirit. Travel safely, girlfriend. Send postcards. Bottoms up!

Care to see much more?

Visit Ruthie’s own website, where you can see galleries of her wildlife photography from around the world.