Simon Wiesenthal, best known for helping to bring former Nazis to justice, including Adolph Eichmann in 1961, survived five concentration camps.

89 of his family members didn’t.

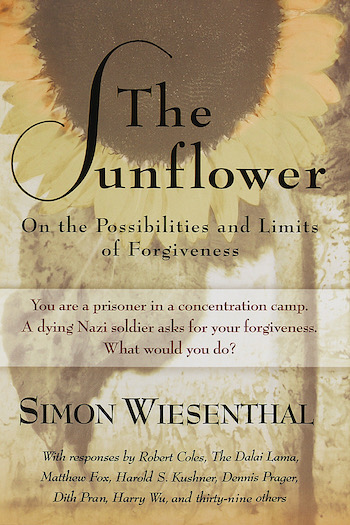

In his book, The Sunflower, Wiesenthal relates a small but searing interaction he had while in a camp in Poland. The day began with his passing by a cemetery where a sunflower bloomed atop each grave. “Suddenly I envied the dead soldiers,” he writes. “Each had a sunflower to connect him with the living world, and butterflies to visit his grave. For me there would be no sunflower; I would be buried in a mass grave, where corpses would be piled on top of me. No sunflower would ever bring light into my darkness, and no butterflies would dance above my dreadful tomb.”

Later, laboring on a project at a military hospital, Wiesenthal is approached by a nurse.

“Are you a Jew?” she asks. She beckons him to follow her and leads him to the bedside of a dying S.S. officer.

Covered in stained bandages with openings for his nose, mouth and ears, the patient whispers, “I know the end is near.”

Wiesenthal writes he was “unmoved. …The way I had been forced to exist in the prison camps had destroyed in me any feeling or fear about death.”

The patient says he was raised Catholic. When the war started, he’d joined the Hitler Youth, hoping “to see the world.” He grips Wiesenthal’s hand as he speaks. When Wiesenthal tries to withdraw his hand, the patient grips tighter. Wiesenthal writes, “I began to ask myself why a Jew must listen to the confession of a dying Nazi Soldier. If he had really rediscovered his faith in Christianity, then a priest should have been sent for…”

Wiesenthal “wanted to get away,” he writes, but “all of a sudden I felt sorry for him.”

The patient, whose name is Karl, says, “We were told the Jews were the cause of all our misfortunes… They were trying to get on top of us, they were the cause of war, poverty, hunger, unemployment…”

Karl speaks of his battalion’s coming across about 150 Jews, mostly women and children. The soldiers force them to carry cans of petrol into a deserted house, then crowd them in the house and set it on fire.

“I knew how this story would end. My own country had been occupied by the Germans for over a year and we had heard of similar happenings. …The method was always the same. He could spare me the rest of his gruesome account. So I stood up ready to leave, but he pleaded with me. ‘Please stay. I must tell you the rest.’”

Wiesenthal recalls. “He was so shattered by his recollection that he broke into a sweat and I loosened my hand from his grip. But at once he groped for it again and held it tight. He spoke of additional atrocities, then sighed and whispered, “My God, my God.”

Wiesenthal writes, “For this dying man and for his like there could be no God. The Fuhrer had taken His place.”

The soldier says, “The pains in my body are terrible, but worse still is my conscience. …I am left here with my guilt. In the last hours of my life you are with me. I do not know who you are. I only know that you are a Jew and that is enough. I want to die in peace, and so I need…”

Wiesenthal writes, “I saw that he could not get the words past his lips. But I was in no mood to help him. I kept silent.”

The patient says, “I know that what I have told you is terrible. In the long nights while I have been waiting for death… I have longed to talk about it to a Jew and beg forgiveness from him. Only I didn’t know if there were any Jews left…”

Wiesenthal writes, “Two men who had never known each other had been brought together for a few hours by Fate. One asks the other for help. But the other was himself helpless and able to do nothing for him.

“I stood up and looked in his direction, at his folded hands. Between them there seemed to rest a sunflower. At last I made up my mind and without a word I left the room.”

Wiesenthal remains uncomfortable about his interaction with the dying man, unsure if he’d been right or wrong in not expressing forgiveness. Eventually he is sent to a concentration camp in Mauthausen, Austria. There he meets Bolek, a Polish man who, before the war, studied for the priesthood.

“Bolek,” Wiesenthal says, “you would have been a priest by now if the Nazis had not attacked Poland. What do you think I ought to have done? Should I have forgiven him? Had I in any case the right to forgive him? What does your religion say? What would you have done in my position?”

Bolek says, “…One thing is certain: you can only forgive a wrong that has been done to yourself. Yet on the other hand: whom had the SS man to turn to?”

“So he asked something from me that was impossible to grant?”

“Probably he turned to you because he regarded Jews as a single, condemned community. For him you were a member of this community and thus his last chance.”

Bolek and Wiesenthal argue the point at length.

Wiesenthal: “Had he come to the right person? I had no power to forgive him in the name of other people. What was he hoping to get from me?”

Bolek: “In our religion, repentance is the most important element in seeking forgiveness. And he certainly repented. You ought to have thought of something. Here was a dying man and you failed to grant his last request.”

Wiesenthal: “That’s what is worrying me. There are requests one simply cannot grant. I admit I had some pity for the fellow.”

They talked for a long time, Wiesenthal writes, but came to no conclusion. “On the contrary,” he adds, “Bolek began to falter in his original opinion that I ought to have forgiven the dying man, and for my part I became less and less certain as to whether I had acted rightly.”

Burton and I received a reprint of The Sunflower from our good friend, businessman and talk show host Jack Krasula. Jack received the print-out from the Trinity Forum, a non-profit faith-based organization that works to “cultivate, curate and disseminate the best of Christian thought.”

The Sunflower tackles a moral dilemma born out of monstrous, immoral behavior. The reprint arrived some weeks ago. The story and the dilemma have stuck with me. Like Wiesenthal, I become less and less certain as to whether he acted rightly.

What do you think, dear reader?

In any case, thanks, Jack, for sharing a powerful but troubling tale.

Thanks, Jerry. Profound answer. Glad the column inspired such an insightful response. Thanks for commenting.

Jerry Shulak emailed me a response. It was so thoughtful I decided to share it with Godsigns readers:

At first it was a dificult decision. As the hours passed my thoughts ran deep. The question returned quickly as if it had dominated my mind all day. I was reminded I had thought throughout my life what it possibly could have been like to live the torture of the Holocaust. To lose familu, fellow Jews and acquaintances and experience execution. The answer came loud and clear:

I would listen quietly and make certain he knew I heard his death door confession and feelings. I would have gently pulled my hand away as he began to speak. He would know I was present and had heard him. When he finished I would touch his hand quickly to reassure him of my presence. I would tell him I heard him. My final words would be, “Go now. Search for peace in your travels through death as I will when my time comes.”

Quietly and quickly I would exit. I would fight to still the inthinkable thoughts and try to go forward. I will go forward. I must. I will never understand the pain one human can render upon another.

as emailed by Jerry Shulak

What a difficult question. I need to think deeply about my answer. Always been learn and forgive. A go forward guy. What went on and what is going on with torture and killing is a whole different introspection.

Thanks, Jerry. I’m still pondering.

He was asking the wrong entity for forgiveness. In my opinion. I would have said pray for forgiveness to the One

Thanks for commenting, Tim. A tough one for sure.