Movie Info

Movie Notes

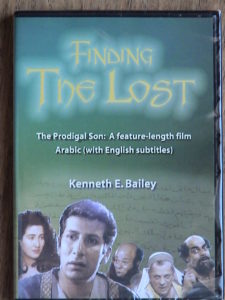

(Arabic with English subtitles)

A Face Book posting about the wonderful N.T. scholar Kenneth Bailey reminded me that he also produced a feature length film which I reviewed in the March 1994 issue of Visual Parables. Here is that review t hat should be of interest to anyone who teaches or preaches the 15th Chapter of the Gospel of Luke. Also available on DVD, and of great use, are several of Dr. Bailey’s Biblical lectures.

Movie Info

- Director

- Anis 'Atiyyah

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 50 minutes

- Rating

- Not Rated

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 2/10

- Language

- 0/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 1/10

- Star Rating

If you want to explore in depth the Gospel text for March for March 22 (The 15th Chapter of Luke), then Harvest Communications has just the film for you. We have never had an Egyptian film to review before, and certainly not a film by a well-known Biblical scholar. If you have followed the work of New Testament scholar Dr. Kenneth E. Bailey, you might recall that in 1973 Concordia published his book THE CROSS AND THE PRODIGAL: The 15th Chapter of Luke, seen through the eyes of Middle Eastern peasants. The first 73 pages of the book consisted of a study of the chapter in Luke from the author’s vantage point of growing up and living in Middle eastern villages. The last half of the book consisted of Dr. Bailey’s play dramatizing the parable of the Father and Two Sons. The film is an enlarged revision of that play in which the other, shorter parables of lostness — The Lost Coin and The Lost sheep — are skillfully woven into the tapestry of the main story, in that the shepherd who goes out seeking the lost sheep works for the Father, as does his wife who loses and then finds the coin. The film adds characters to the short parable, the family’s servants, villagers, the citizens of the “far country,’ even a possible love interest in the person of Athena, the daughter of the owner of the pigs.

The film opens with the villagers subjecting a man to the Kezaza ceremony. He has violated the Jewish property laws by selling or losing property to a Gentile. This “cutting off” banishes the man from all social intercourse with the community, as well as subjecting him to a beating. The depiction of this harsh practice, referred to in the Mishnah and the Babylonian Talmud, forms the background of the fate that could befall the Prodigal upon his return.

The young son Salim (Hani Ramzi) longs for what he thinks is the freedom of living on his own, beyond the watchful gaze of his Father (Samir Fahmi) and the competitive presence of his older brother Aziz (Jamil Barsum). Against the advice of others Salim decides to ask his Father for his share of the inheritance, even though this means in effect that he is willing the death of the old man, because usually property was divided only at the death of the father. The Father is disposed to grant the son’s wish, even though it breaks his heart. The old man argues that he cannot force his sons to love him. They must have the freedom to make their mistakes and learn how much they are loved.

Salim is still faced with the problem of selling the land of his inheritance, because no one in the village would dare buy it, thus removing it from the family originally owning it. The young man thus seeks out a Gentile buyer. No wonder why he must depart for a far country, in order to escape the terrible Kezaza ceremony, once the villagers learn what he has done.

Things go well in the far country. The young man believes that at last he has found his longed-for freedom. Fine clothes and feasts, and lots of friends willing to keep him company — until the money runs out and he is broke. Then, when a famine overtakes the country and no decent work can be found, it is off to feed the pigs. Athena (Iman), daughter of his employer, is the Prodigal’s sole friend, encouraging him to leave and return to his own country. There is a hint of a romance here, but unlike in Hollywood films, she follows the binding customs of her time and remains behind when Salim finally decides to go to his Father and ask to be taken on as a slave.

Meanwhile the Father is pining for and praying for his lost son. Matters are strained with the Aziz, who in, spirit at least, has also left the Father. When the Prodigal is spotted from afar, the Father, against all social custom, runs out to the boy. This is not just because of his eagerness to greet his son, but to prevent the villagers from seizing the boy and inflicting the Kezaza ceremony upon him. Everyone is astounded at the Father’s act, including the Salim. The rest of the story is familiar, the bedecking of the returned son with rings and new clothing, and the fine feast. And of course, the displeasure of the older son and his refusal to come in to the feast. In this version Salim goes out with his father to beg Aziz to join them. When Aziz will not listen to their Father Salim tries to explain that their father has paid a great price for his reconciliation and that the older brother is a sinner also. This so enrages Aziz that he raises his staff in anger to strike at the Father and younger son. The frame freezes at that moment, revealing that the staff intersects with a horizontal pole to form a cross, reminding us that such forgiveness and reconciliation is costly, and not a matter of cheap grace. The village Patriarch gives up his dignity and his right to extract penance from the wayward son, instead throwing him a lavish welcome home party — and when the older Son refuses to come in, he even leaves the party to plead for his presence.

The well-produced film begins and ends with a text in Arabic scrolling down the screen. Unfortunately, there is no English text given for this, so Dr. Bailey has sent his translation:

At the beginning: “In the first century, in Palestine, on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, Jesus of Nazareth moved among the people and proclaimed his message of costly love and reconciliation. Often, he told parables. From among his parables three of the greatest are the stories of the lost sheep, the lost coin and the two lost sons. These three parables, recorded in the Gospel of Luke, are the subject of our Film.”

At the end: “The ending? Perhaps this is the beginning of the parable which Jesus of Nazareth proclaimed at the beginning of the first century. As Jesus told the parable it has no ending. Thus, we also have left our film without an ending. Indeed, in the two sons Jesus placed all his hearers on the stage and presented himself as the father who offered costly love to both his older and his younger sons. The listeners themselves were obliged to finish the story. In that age the ending was acted out in the Cross. Like them, we also must listen to his story and decide for ourselves what we are going to do with Jesus.”

Filmed in Cairo by a Cypriot company, Director Anis ‘Atiyyah at first ran into difficulty with the Egyptian crew, who were Muslims. It seemed obvious to them that the Father represented Allah, and because it was blasphemy to depict Allah in any visual form, they raised strong objections to the script. A call brought writer Ken Bailey to Cairo. On the flight dr. Bailey settled upon the way around the objections: he told the crew that the story was about Luke 6:32, “Be ye therefore merciful.” This is one of the great attributes of Allah taught by Islam, as well as by Christianity. The crew and the government censors accepted this, and the filming proceeded. The cast of professional actors, used to appearing in Arabic soap operas where they could often change the script’s dialogue had to be dissuaded from making changes, because so much of the dialogue was important theologically. The result is a film that any producer would be proud to claim, the most thorough and authentic treatment of the Father and Two Sons ever filmed.

FINDING THE LOST (1 hour 50 minutes) available for $20 from Harvest Communications, 900 George Washington Blvd., Wichita, KS 67211 (1-800-776-6168) Order Series #76202.

The above was written almost 25 years ago, so if Harvest Communications is no longer in business, Crossways International lists this DVD, along with several of Dr. Bailey’s lectures.