Movie Info

Movie Info

- Director

- Julia Taymor

- Run Time

- 2 hours and 3 minutes

- Rating

- R

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 4/10

- Language

- 2/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 6/10

- Star Rating

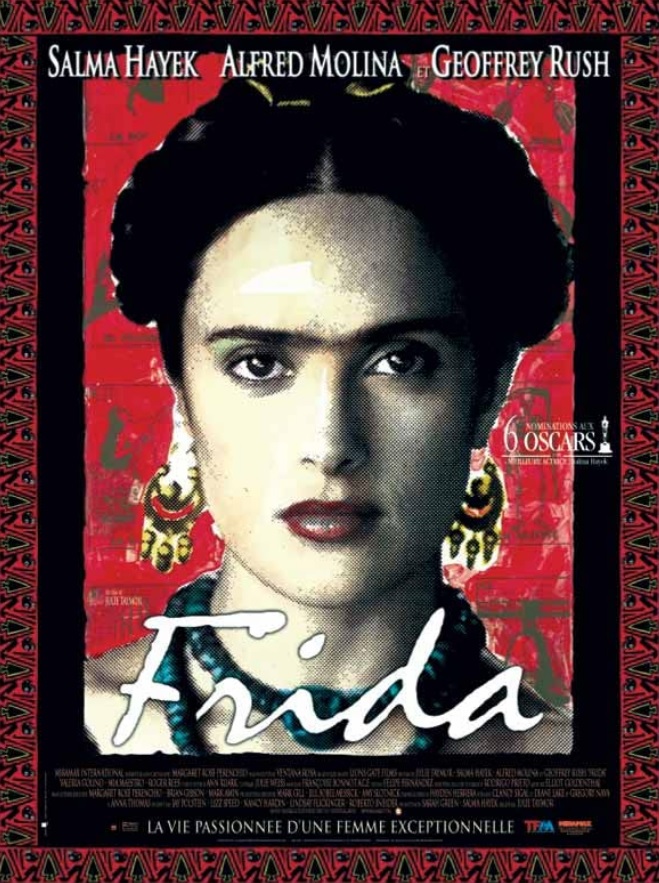

I am bringing up from the archives this 2002 review of the film Frida because of a Secret San Francisco web gateway to Frida Kahlo’s life and work. If you click on this link, you’ll visit that website.

Actress Salma Hayek, who plays the artist Frida Kahlo spent eight years in bringing Frida to the screen. Engaging Julia Taymor, of Broadway’s The Lion King fame, and six writers, she finally managed to bring the controversial artist’s life to the screen—but, if you’ve read reviews by other critics, you know that the film fails to bring it to life. The set pieces of that life—her first sight of Rivera (Alfred Molina) at work, her horrible bus accident, her tempestuous marriage to Rivera, their sojourn in America and his disagreement with Nelson Rockefeller (Edward Norton) that led to the destruction of Rivera’s mural in the lobby of Rockefeller Center, her long bouts with disability, and her plunge into Communism which included their giving shelter to Trotsky (Geoffrey Rush) when he fled from Stalin, and her many love affairs—all these are portrayed, but the over the top passion of the two artists barely emerges from the performances.

Despite its failings, I liked the film, and certainly found it more comprehensible than Paul Leduc’s 1984 film Frida, naturaleza viva. The film is visually beautiful, not just in the scenes in which we see some of the works of Frida and Diego, but in its style and costuming. There is a lovely moment when we look through the artists’ apartment window during their stay in New York City and see one of Frida’s bright peasant dresses she favored hanging on a line, snow falling around it, which is later incorporated into one of her paintings. The filmmakers often soften some of the facts, such as the freedom-loving Kahlo’s ironic adoration of Stalin—no “God that failed” for her; even after his murderous purges she maintained her devotion to the end of her life, as can be seen by her inclusion of the dictator in some of her later paintings. (She left an unfinished portrait of him on her easel at her death in 1954.) I wonder if she had gone on from her trip to Paris and spent time in Moscow and seen the deplorable climate of fear resulting from his tyranny, would she have continued in her naïve adoration of him?

Forgivable liberties are taken with some facts, such as the opening scene in which we see her being carried in her lofty bed out the door and through the streets, a puzzling scene at first, until later in the film we discover that she is being transported to the first major showing of her work in Mexico City. Her doctor had ordered her not to leave her bed. But how could she miss the event when at last in her own country (there had been highly successful exhibits in the United States) she is being honored? So, she follows orders by staying in bed, but having it transported to the gallery where she can bask in her well-deserved glory. Actually, she was taken to the gallery in an ambulance, but the bed was moved there, from which she presided at the festivities.

There is much about her life deplorable to people of faith, such as her sexual license, some of it perhaps indulged in to offset that of her womanizing husband (he had pledged to be loyal but not faithful). Her politics we can understand, growing out of the Mexican Revolution and centered on the struggle against oppression. She and her husband supported the Loyalist cause during the Spanish Civil War, and even after the amputation of her leg shortly before her death, she participated in a demonstration opposing the U.S.-led coup that toppled the democratically elected, but leftist, President of Guatemala. What we come to admire the most about the artist is her devotion to Rivera—and he to her, despite their mutual infidelities which led to a divorce and brief separation—and her dedication to her art. Influenced by Mexican native art and its indigenous religion, as well as her accident and 32 subsequent operations, she created almost surrealist canvasses that challenge the imagination. Despite long periods confined to bed in a body cast and uncomfortable braces, she triumphed over the pain that was ever present with her, and indeed, which she incorporated into her paintings. This was a woman who poured her loneliness and pain into her art, adding to its uniqueness and power. She might deserve a better picture to memorialize her, but this one will have to do in the meantime.

Note: To better appreciate the artist’s work pick up Andrea Kahlo’s book KAHLO, a part of the Barnes & Noble series on great artists. Costing less than $8 or $9, and available at their bookstores, it reproduces her major paintings and gives a good summary of the events of her colorful life.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120679/