Movie Info

Movie Notes

When this review was posted 6 years ago I failed to include it and the discussion questions in that issue of the journal. I post both now because the film is being discussed via Zoom early in December. See my current blog for how you can join in this nation-wide discussion.

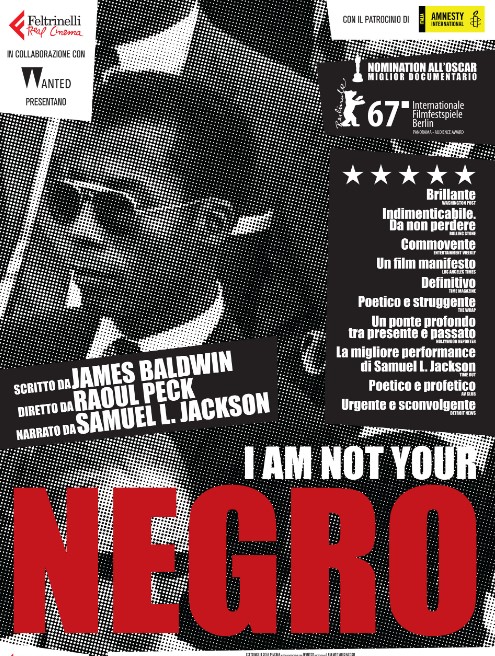

Movie Info

- Director

- Raoul Peck

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 33 minutes

- Rating

- PG-13

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 2/10

- Language

- 2/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 1/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

Woe unto them that decree unrighteous decrees,

and that write grievousness which they have prescribed;

To turn aside the needy from judgment,

and to take away the right from the poor of my people,

that widows may be their prey, and that they may rob the fatherless!

Jesus answered, “The first is, ‘Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one; you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’ The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.”

When I was in seminary and beginning my ministry James Baldwin through his provocative writings made a deep impression on me. Many times, I quoted his statement that being a black man in America meant being in a perpetual state of rage. His polemical The Fire Next Time I regarded as every bit of a God-sent prophecy as the denunciations of injustice hurled forth by Amos and Jeremiah. And now we see, thanks to this work by film-director prophet-Raoul Peck, that Baldwin’s words are as relevant today as they were a half century ago. Despite what the naïve Supreme Court justices thought when they ripped out the heart of the Civil Rights Act, racism is still almost as strong as it was when Jim Crow laws kept “Negroes” in their place. Racism has just gone underground, those still under its sway defending themselves by using the term “political correctness” against anyone who would call them out on their remarks and acts (usually disguised by code words and phrases such as “law and order”).

The Haitian-born filmmaker in a way finishes a work that Baldwin was working on at the time of his death in 1987, Remember This House. He had completed just 30 pages and was hoping to visit the survivors of the three prophets he had cherished as friends, murdered between 1963 and 1967, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. As we see words addressed to his literary agent typed onto the screen, Baldwin wanted “these three lives to bang against and reveal each other, as in truth they did, and use their dreadful journey as a means of instructing the people whom they loved so much, who betrayed them, and for whom they gave their lives.”

The author’s text from his unfinished book is scattered throughout the film, read forcefully by Samuel L. Jackson. We hear Baldwin himself in numerous clips from his TV appearances and speeches on college campuses. All of these quotations provide evidence of what an articulate and courageous observer he was, a true prophet willing to call out liberal whites, as well as rabid segregationists, on their shortcomings. Whites too often, Baldwin observed, thought racism to be an individual affair, conquered by converting the individual, when in reality it was systemic, embedded in our culture. The director also inserts archival photos and news clips from Civil Rights demonstrations and clips of his three friends, as well as photos and clips from ads demeaning to blacks, the latter including scenes from Hollywood films. None of the black screen characters, he says, acted like any black person he knew.

The film clips will be of special interest to VP readers. They go back to the silent era’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Thirties era King Kong, Dance, Fool, Dance, and the Stepin Fetchit movies with their negative image of blacks. Films from later on include Imitation of Life, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? and The Defiant Ones. Baldwin’s comments on the latter remind me of my surprise years ago, when I first read his report of the reaction to the film of the audience in Harlem. Like other whites, I saw the film, about a black and a white convict (played by Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis) escaping while still chained together, as an appeal to racial brotherhood because their hatred of each other slowly changes to mutual respect. Blacks saw it otherwise. The two convicts manage to break the chain that had bound them together. When Poitier’s character jumps aboard a slow-moving freight train, Curtis’ almost reaches the black’s outstretched hand, so he can be pulled aboard. Failing to do so, the Black jumps off, now unwilling to abandon his friend. Baldwin approvingly reports that the Black audience yelled, “Fool! Get back on the train!” The author points out that liberal depictions of Black-White relations in film are attempts to get blacks to let whites off the hook and make them feel better without really facing up to the enormous damage that racism has inflicted on blacks—and on whites as well.

Early Hollywood’s negative view of blacks was carried over into print, a series of shameful magazine ads depicting blacks only in servant roles, adding a touch of color to the mostly B&W documentary. (Aunt Jemima was just one of many such servile characters.)

Just as traditional Christianity teaches the total depravity of humanity, Baldwin teaches the total depravity of American society because of the embedded racism in it. Indeed, he fled his native land to Paris so that he could experience for the first time a sense of freedom, but felt compelled to return to the U.S. when the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum. He says that he wanted to be a witness (and participant) to the struggle to change America, rather than watch it from afar.

Baldwin wrote as an outsider, pointing out that he was not Black Muslim, a Black Panther, nor a Christian –the latter, he says because the church did not practice the command to love the neighbor. He also might have added that the intense loathing of homosexuals of most of church leaders and members at the time also put him outside its pale. (There is just one mention of his homosexuality in the film, revealed in an excerpt from a report by the FBI that kept a watch on him because Hoover saw the writer as a Communist endangering the security of America.)

Because of his repeatedly calling out the “moral apathy of American whites’, viewers might be reminded of Baldwin’s friend’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in which Dr. King denounced his Southern white detractor’s, some of whom considered themselves liberal, and complained that he was pushing racial matters too hastily. By including scenes from Ferguson and recent police beatings and shootings (including Trayvon Martin’s murder), the director shows that the Black Lives Matter movement is very much needed.

This is truly a movie that matters, and should be seen and discussed along with another film that ought to dispel illusions that racism has been defeated, Ava DuVerna’s 13th. Some have called racism “America’s Original Sin.” When Jesus’s summary of the Law is read, it is apparent that it is indeed the church’s, given the long history of so many of its members’ complicity in the slave trade, slavery, and the maintenance of segregation. All religious leaders who believe that the Scriptures have relevance to current life should be calling this important film to their people’s attention!

In closing, I leave you with these Baldwin quotes to ponder:

“The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. It is not a pretty story.”

“What white people have to do, is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place, because I’m not a nigger, I’m a man, but if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it.”

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed that is not faced.”

Note: My review of this director’s film Lumumba, telling the story of America’s complicity in the murder of the African leader, can also be found at visualparables.org

For Reflection/Discussion

Page numbers refer to those in the film’s companion book of the same title, which contains much of the film’s narration and photos.

- What has your experience been in regards to James Baldwin and his writings? How does he make you feel?

- He focuses upon three African American leaders: Medgar Evers; Malcolm X; Martin Luther King, Jr. (pp. 3-7) Is there one of them which you especially admire or are interested in; which one, and why?

- How were they different from each other in their beliefs and methods?

- A White Citizen’s Counsel leader urges white parents to take their children out of integrated schools (p. 11): was the reaction of whites in the North much different—the hatred MLK, Jr. faced when he took up residence in Chicago; riots in Boston over busing of children to integrate schools; redlining by banks and realtors to keep suburbs white; organization of private schools by white parents (often in the guise of “Christian” schools)?

- Where was Baldwin living at the beginning of the C-R Movement, and why did he return to the US? Without knowing any specifics about her, what do the photos of 15-year-old Dorothy Counts being verbally assaulted by whites reveal about the girl’s character? Can you imagine yourself or your teenage daughter going through such an ordeal? (12-15)

- We see a series of ads featuring African Americans: how are they depicted? Positively or negatively? What effect would such images have on children?

- From the clips shown, how were Blacks depicted in the movies? What effect does this have on Baldwin as a child in regard to his view of heroes and villains? Why was Uncle Tom “not a hero for me”? What did John Wayne fighting Indians teach the young Baldwin about himself? (How is this similar to the famous experiment in which Black children were to choose between Black and white dolls?) What was the “shock” he and other Blacks his age (from 5 to 7) experienced? (pp. 22-23)

- What, or who, saved James Baldwin from hating all whites, as the Black Muslims taught? How does Bill Miller demonstrate the important, and lasting, effect that a school teacher can have on a person? (p. 19)

- In the segment in which he describes his first meeting with Malcolm and Medgar Baldwin calls himself a “witness,” and not a participant: how is this an important distinction for him—that he is neither a Christian nor a Black Muslim? (pp. 24-34)

- What do you think of Baldwin’s affirming the positions of both Malcolm X & MLK, Jr? In what sense do you think he means that their positions at the end were “virtually the same? In the author’s opinion what has racism done to whites? How do they demonstrate that some are indeed “moral monsters”? (pp. 35-39)

- Baldwin says that whites do not know Blacks, when at that time segregationists were telling C-R “agitators” that they knew “their nigras” were contented with conditions until the agitators stirred them up—which was right? Remember Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask”? (p. 40-41))

- What do you think of the “Baldwin-Kennedy Meeting”? (Note how Baldwin in the film provides just a fragmentary glimpse at it.) What did the Blacks want the Kennedys to do? How would this have made a difference? Why did playwright Loraine Hansberry walk out? (pp. 42-44)

- What do the following film clips reveal: (pp. 55-66) a. The light-skinned school girl and her mother from Imitation of Life? Why is the girl ashamed of her mother? b, Curtis & Sidney Poitier fighting and running from The Defiant Ones? Why did Blacks react differently from white audience members? c. Why, according to Baldwin, did Black people dislike Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? Was the couple ever shown kissing? d. How was the last scene (of In the Heat of the Night) between the racist sheriff and the Black detective one of reconciliation?.

- Why did Baldwin and his blond girl friend take such elaborate precautions when they went out in public—after all, this was in New York City, and not Birmingham, Alabama? (p. 67)

- How did the documentary clip with its positive narration about Negro progress paint a false picture? Why is Baldwin skeptical and bitter over Robert Kennedy’s prediction that within 40 years a Negro might be elected President? We did elect Barack Obama twice, but what happened afterwards? How did the backlash show the shallowness of liberal whites and the depth of Baldwin’s understanding of racism? (pp. 68-71)

- Baldwin speaks of “cheap labor” being the basis of our nation’s economy: how does this compare with what our schools have taught, that our nation grew by the courage and hard work of pioneers’ taming the wilderness? (p. 75-77)

- What do you make of the series of apologies? (p. 78) Who needs to apologize, and why?

- After telling how he heard of MLK’s death, Baldwin quotes a Black saying that now that they (whites)” don’t need us, they’re going to kill us all off. Just like they did the Indians.” Given that all three of his friends were murdered, what might you say in reply? (pp. 80-81)

- Baldwin speaks of TV and the “American Fantasy” and says that American entertainment is narcotic: how is this so? (pp. 82-91) In the sequence in which he describes the impact upon himself of the murder of Dr. King Baldwin speaks of the failure of “the American Way of Life” and says that there are “two levels of experience,” represented by Gary Cooper and Doris Day, and Ray Charles. What do you think he means by this? (pp. 92-103)

- What do you think is the answer to Baldwin’s challenging observations, “”What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a ‘nigger’ in the first place, because I am not a nigger, I ‘m a man”? How is “n—” an invention, and why?