Movie Info

Movie Info

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 29 minutes

- Rating

- Not Rated

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 1/10

- Language

- 0/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 2/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

Do not judge by appearances, but judge with right judgment.

When I discovered this 1947 film on YouTube, the main reason for watching it, other than the hope for some good jazz, was that it featured singer Billy Holiday in her only film, other than a short made back in the 30s. She plays a singer named Endie whose boyfriend is Louis Armstrong (playing himself). Part of the movie is true, the part about the authorities shutting down the jazz section of New Orleans known as Storyville at the insistence of U.S. Navy authorities. The black residents were evicted, as depicted in a very dramatic scene, and many of the exiled musicians did fan out over the country, bringing their version of jazz to the rest of the country—but not in the hokey (and racist) way shown in this film.

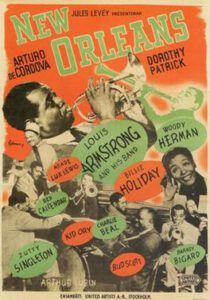

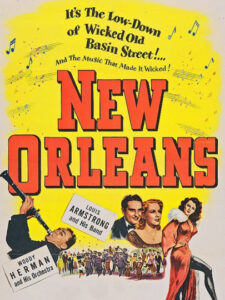

This being 1947, Hollywood was not about to make a movie centered on a Black couple. The stars are Dorothy Patrick as Miralee Smith and Arturo de Córdova as Nick Duquesne. What? You never heard of them? Well they’re White, so naturally in those days when folks on both sides of the Mason-Dixie line boasted, “I’m free, white, and 21,” so the Blacks, as usual, took a back seat in what passes for a plot. Look up the movie on IMDB, and you’ll see that even the movie’s posters are segregated—two of them show just Whites, with Woody Herman being the musician; and one features the Black cast. No problem in figuring out which audiences these were directed at.

The thin plot concerns aspiring opera singer Miralee Smith and her mother (Irene Rich) arriving (by steamboat, of course) from Boston to stay with relatives while arrangements are made to launch her career as a concert singer. Billy Holiday’s Endie is a maid at the relative’s home Miralee and her mother are staying in. During off hours she hangs out at the jazz club where Louis and his band work, often singing with them. Upstairs owner as Nick Duquesne runs a gambling casino where Miralee’s mother enjoys the games. Miralee sneaks into the club and falls for the music there—and even more for Nick. Mother, of course, opposes both the music and her daughter’s choice of a man, and one thing leads unto another until eventually the Forces of Morality close the area down. Nick, alone, moves to Chicago, discovers there is more money to be made in jazz than in illegal gambling, and so becomes the impresario who hires the jazz musicians for clubs and concerts all around the country. Whites once again appropriate for themselves riches created by Blacks!

The film is similar to others at the time in that the rulers of society regard classical music as the proper music for decent people and judged jazz and other forms of popular music as vulgar and demeaning. Mrs. Smith even assumes the role of hypocrite by gambling upstairs while forbidding her daughter to listen to the music downstairs. All this is simplistically resolved, of course at the end.

After the movie was released, Billy Holliday complained about her character being relegated to that of a maid, saying that she did not want to be one in real life or in the movies. She also lamented that “miles of footage of music and scenes” were shot that was cut. If only it were saved and discovered some day! Judging by what has survived, it would be a real treat.

Despite the silly plot, I urge you to watch this film and talk about it for two reasons—first, the wonderful music and second, for a case study in white racism.

The music is a joy. Billy sings well “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans” and “The Blues are Brewin’,” but her rendition of the blues song “Farewell to Storyville” is especially touching as she leads the long procession of Blacks through the street. Louis and his band liven up the screen with their rendition of “Endie” and “Where the Blues Were Born.”

Billie disappears from the picture after Nick moves north, and the second time that we hear “Do You Know What It Means…” it is Miralee who sings it at her big debut concert in New York City. It’s OK, but there is none of Billy Holliday’s soulfulness stemming from a real loss. After singing the traditional opera fare, Miralee encores with the “low life” song, much to the gasps and consternation of the traditionalists in the audience, and to the delight of the open-minded. And the band accompanying her? Not a Black musician on the stage! It is Woody Herman’s band. No, not band, but orchestra—larger than a symphonic orchestra with dozens of strings, indeed so many that if they were playing in that New Orleans, there would have been no room for the patrons!

Now none of this travesty is meant to be mean. Director Arthur Lubin and screenwriters Elliot Paul and Dick Irving Hyland are all white and do as they are told, probably not suspecting how demeaning their treatment is of the originators of what some have called the only original American music. For the next thirty years the White controllers of the music and communications industry will favor Whites over Blacks, rerecording a song by Blacks for White performers, who reap huge profits when the song makes the Hit Parade. (Ken Burns calls this to attention in his magnificent series Country Music.) Anyone studying systemic racism and how it permeates our culture would do well to include this film. It’s both instructive, and, thanks to the music, also fun—and it expands the meaning of “whitewashing”.

To see the film on YouTube click here.

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5vL7l6XBYI)

This review will be in the October issue of VP along with a set of questions for reflection and/or discussion. If you have found reviews on this site helpful, please consider purchasing a subscription or individual issue in The store. You will discover that your $39 pays for not just 12 issues of a journal that includes the discussion questions for the films, but a large archive of over 2200 films and even more reviews and special articles in all past issues of Visual Journals dating to 2012.

Is there a vinyl movie score for the 1947 movie “New Orleans” starring Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday available, new or used?

Sorry, but I don’t know of one.