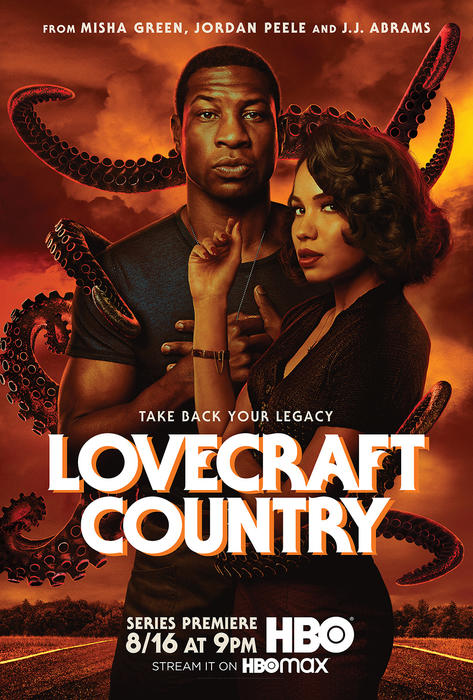

I am assuming that you have read my review of HBO’s exciting new series Lovecraft Country and so know that it combines themes of racism with science fiction and fantasy horror, its three protagonists being African Americans. If you have not, then click on the title below and read that first, else much of the following will not make sense.

In my review of the first thrilling episode of HBO’s Lovecraft Country I referred several times to my past indulgence in science fiction during the early 1950s when I lived in Indianapolis, Indiana. Like Atticus in Lovecraft Story, I was such an avid science fiction fan, and to a lesser extent of fantasy, that I joined, along with my best high school friend, newly formed Indiana Science Fiction Association. We were among the younger of its 20 members, the older ones consisting of teachers and other professionals, some of whom were married. Scattered over Indianapolis and northern Indiana, we met in members’ homes around the state. I was working after school at a grocery store and thus was able to own a car in which we traveled by the carload to the monthly meetings. (Since we did not stay overnight, this often meant returning to Indianapolis in the wee hours of the morning. I won’t say how fast I drove to save time because some of my grown children might see this.)

Near the beginning of Lovecraft Country Atticus is reading The Princess of Mars while traveling on the bus, a book I never read, but I did devour all of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan novels and one of the John Carter of Mars books when I was in junior high school. I did share Atticus and George’s love for Ray Bradbury and Robert Heinlein’s stories. Like George, I collected s-f magazines and books, once possessing one of the most nearly complete runs of Astounding Science Fiction magazines in the state–from 1931 through 1956. ASF was the high-brow pulp publication in the field for many years, until it was joined in the 50s by The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and Galaxy.

Two members of our ISFA (as we called our club, and then its fanzine) went on to fame and glory in the sci-fi world, Robert “Buck“ and Juanita Wellons Coulson. They had not been married very long when they helped form our club in the early 50s. Juanita played the guitar and sang, even writing a number of songs based on the stories of Robert Heinlein. A highlight of many of the meetings was her unpacking her guitar and singing her songs. My favorite was her lovely “The Green Hills of Earth,” based on Heinlein’s story of that name. (It was a sad day when my 78-rpm recording of the song was cracked.) She and Buck published a fanzine called Yandro which won many awards in later years.

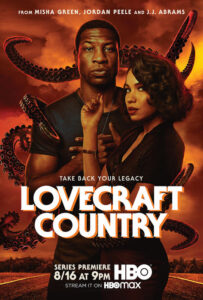

I was so enthused that I volunteered with a friend to publish ISFA’s fanzine, which we unimaginably named ISFA, dipping into my savings to buy a used mimeograph machine for publishing it. Juanita and Buck contributed to all 12 issues that we were able to publish: he articles, and a book review column called “The Unquiet Grave,” and Juanita several articles, a short story, and in every issue, numerous illustrations. (She was multitalented!) That was a great time for receiving mail, with large envelopes of art and manuscripts arriving frequently. This was my greatest joy in late high school and in college, with most of my time taken up by what I considered drudgery– classes and work at a grocery store to help pay the bills (my divorced mother’s salary as a department store employee was pretty meager.)

ISFA sold for $0.15 an issue and included anywhere from 18 to 45 pages. Included were short stories, articles (often parodies of other works), book & film reviews, art folios, and letters from readers. (My first film review appeared in this, as well as a couple of satires.) As word spread about the journal we attracted as many readers outside Indiana as within it.

Too often the mimeographing was spotty due to a not so good machine or poorly typed stencil, but the features that distinguished it was a wrap around cover and some excellent artwork–Juanita’s drawings were joined by some beautiful work by good artists whose only compensation was one or more free copies of the issue.

The first covers were poorly reproduced, but when I experimented with yellow ink on black, they looked much better, the highlight being the full-color one reproduced here. Artist Marvin Bryer had access to a color press, an unheard-of asset for a fanzine until his came out. This was our only full color cover.

Interestingly, in this same issue I have just come across a 4-page article by Neal Wilgus entitled “On H.P. Lovecraft and Maps. “(Smoking Rockets! I just Googled the author’s name and see that he also is a prolific writer ! ) The article, pointing out that the fictional Arkham is based on Salem, includes two 1/2 page maps and one full page map–respectively, of the area north of Boston and Lynn showing where the fictional Arkham, Dunwich, and Innsmouth are located in Lovecraft’s universe; a street map of tiny Innsmouth; and a similar map of the larger Arkham, showing the southern part of the town south of the Miskatonic River (also fictional ). I had no idea when I started to write this blog, which led to my searching through my collection of ISFA, that ISFA would be so relevant!

I should mention that another member of our club Gene DeWeese also contributed occasionally to ISFA and gained some fame as a sci-fi writer and author (with Robert Coulson) of a Star Trek novel and of several books in the Lost in Space and Dinotopia series.

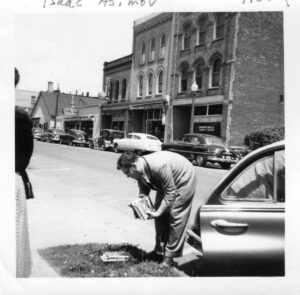

One further matter to briefly discuss is how rare back in the 50s it was to meet a Black science fiction fan. Our club was entirely White, and of the three science fiction conventions that I attended (in Bellfountain, OH where I had an amusing encounter with writer Isaac Asimov*); Chicago; and New York City), I don’t recall seeing any African Americans in attendance. I think they would have been welcome, but they either were very rare, or might have felt they would not be accepted. This was the 50s, after all, the same period that Lovecraft Country is set in–and look what its three heroes are facing far north of the Mason Dixie Line! And this brings me to the name of the first episode of the series.

“Sundown” is not only the episode’s name, but the life-and-death time for our trio to get out of Devon County lest they be shot by a cop, so rabidly racist that he makes Bull Connor look like a “We Shall Over Come”-singing NAACP member. As I mention in my review, I remember seeing such a sign in the late 40s when I was a boy. My father had a sideline to his regular job. He serviced juke boxes and wall boxes in a number of cafes in Anderson and Muncie Indiana. He sometimes took me with him for company, and it was on one such trip that I recall seeing the sign warning a Black to be gone by sundown, or else. I thought it was Anderson but have since learned it was another nearby town.

The sad memory about the sign was that my father saw nothing offensive in it but agreed with its sentiment. He would say back home in Indianapolis that the “N”s wouldn’t stay in their place, but were moving too close to our neighborhood, Indianapolis being more segregated residentially than a Southern city. I learned that the “N” word was okay within the family, but that “Colored” was preferred with company. I owe it to a combination of starting to take church seriously, meeting African Americans in high school and college, and to science fiction that my family’s embedded racism was overcome (but never eliminated–I will always be a “recovering racist”).

Science fiction helped me see, and I assume also many other young readers, the absurdity of racism in that sometimes the hero of more recent stories might be a tentacled or methane-breathing creature. By sympathizing with such a different protagonist, we came to see how silly it is to make a fuss over skin color. Although some writers of fantasy and science fiction might be racist, as was H.P. Lovecraft, the genres themselves evoked acceptance of differences rather than exclusion. And now we have Lovecraft Country with its likable African American protagonists showing how utterly evil racism is.

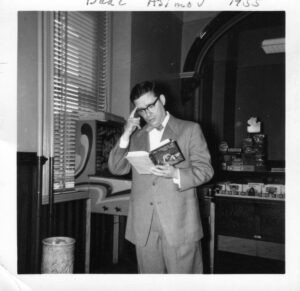

- Here is a photo I took during my chance encounter with the prolific Isaac Asimov. I was taking to my car a stack of ASTOUNDINGS I had bought from a vendor at the Bellfountain Midwest Convention when this short man stopped, picked up one of my magazines, and sneered loudly, “Ugh, science fiction! You read that junk!?” (This reflected society’s opinion of the genre, which my parents also shared, my mother once saying how silly the idea of space travel was because “there’s no air out there for a rocket to push against”–that was the level of scientific knowledge of the general public!) After another comment, the stranger broke out in a smile as he extended his hand while saying, “I’m Isaac Asimov.” Not having seen a photo of him (he was far from finishing his run of 400 books back then), my jaw dropped as I shook his hand and asked for permission to snap his picture.

-

Isaac Asimov looking at my stack of ASTOUNDINGS.

Isaac Asimov at the Bellfountain SF Convention. We loved the sf conventions because most of the professional writers mingled freely with fans.

And I grew up loving any science fiction. I still don’t understand why the world can’t be like Star Trek, and just are people and not race.

Amen to that, Ellen. At least we know that STAR TREK made some contributions to that better world. Thanks for your comment.

Very interesting, Ed! Thanks for sharing!

You’re welcome. I hope to add more later this fall when I buy into HBO & watch the rest of the series. Hope you also see my blog about this. Thanks for your comment.