Movie Info

Movie Info

- Director

- Michael A. Goorjian

- Run Time

- 2 hours and 1 minute

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 4/10

- Language

- 1/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 1/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

Listen to my cry,

for I am brought very low.

Save me from my persecutors,

for they are too strong for me.

Bring me out of prison,

so that I may give thanks to your name.

The righteous will surround me,

for you will deal bountifully with me.

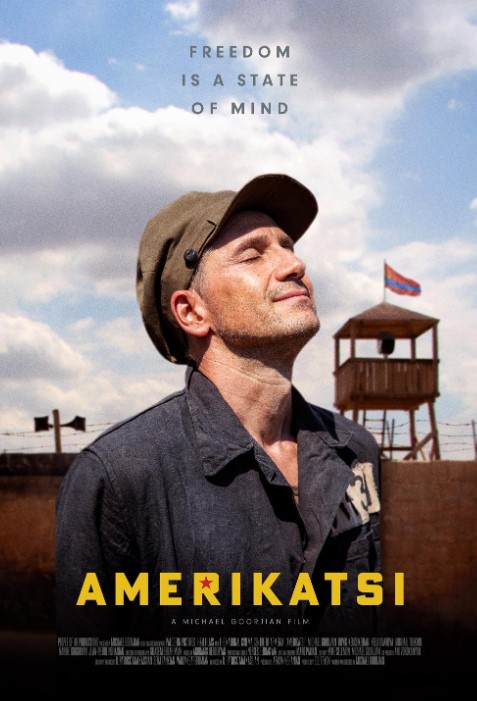

Not since Cool Hand Luke, Shawshank Redemption or Birdman of Alcatraz have I found a prison film so engrossing as director/writer/actor Michael A. Goorjian’s film set in the post-WW 2 Soviet Union. It is a deeply personal film because the filmmaker’s paternal grandparents survived the 1918 Armenian genocide. Out of that tragedy and a decades-long unjust imprisonment Goorjian has fashioned a comedy drama that celebrates the tenacity of the human spirit while honoring his Armenian culture and history.

The opening scene is in 1918 in Armenia where Turk soldiers have rounded up a group of Armenians for execution. A four-year-old boy has been placed in a trunk, so we see the people kneeling on the ground from the boy’s vantage point, helplessly peeking through the keyhole as his mother and companions are shot through their heads.

Jump to 1947 when the grown Charlie (Goorjian) has been living safely in the US. Apparently not feeling at home after the death of his wife, he is among the 100,000 returning to Soviet Armenia at the invitation of Stalin’s repatriation program, even though he does not speak the language. He rescues a little boy from a crowd, and the grateful mother Sona Petrov (Nelli Uvarova) invites him to dinner. She has asked her husband Dmitry (Mikhail Trukhim), a high-placed Soviet official, to find him a good job. Dmitry is cold toward the American and displeased by the American’s making the sign of the cross before they eat, and even by his polkadotted tie. So, that night he orders the arrest of Charlie on charges of religious propaganda, cosmopolitanism, and spreading capitalism.

The arrest is supposed to be temporary, intended to harass and scare the man, but through bureaucratic bungling, the Amerikatsi, as Charlie is disdainfully called, is actually kept and sentenced to be sent to hard labor in Siberia. However, after an earthquake strikes, plans for Charlie are changed, and he is retained in his original cell where he endures scorn and beatings. He is very naïve, with the guards calling him “American idiot” and “Charlie Chaplin.” He is sent to solitary confinement in a tiny cell, where he frequently endures beatings.

The cell has but one window, and it is that window that saves the lonely man’s sanity.

Because the earthquake had knocked down part of the prison wall, Charlie can see into the windows of the apartment building next to the prison. Though he cannot hear anything, he can see the couple living in the apartment as they go about their daily routines—eating, conversing, hosting family gatherings, singing, dancing, and the man painting a picture. With no other distractions, the life of the family becomes Charlie’s obsession. He eventually discovers that the man’s name is Tigran (Hovik Keuchkerian), the guard who spends his workaday in the prison guard tower. Tigran had once been an artist, but had run afoul of Soviet policy, arrested, and forbidden to paint.

Over the years, the husband and wife quarrel more and more frequently. When he abuses her, she apparently decides to leave him, placing the key to the cabinet where her husband hides his painting and artist supplies looped over the neck of a flower vase. The man is so devastated by her departure that he starts drinking heavily. He tries to get to his painting materials but cannot open the cabinet without the key. Charlie tries to will the man to discover the key, but as the days pass, he cannot direct him to the vase, the flowers of which obstruct any view of the string with the key. However, eventually the man brings home another woman—and thanks to a roundabout scheme by Charlie, he finally finds the key. (I forget in what order.)

The happiness of the new couple overflows into Charlie’s stunted life, especially when it become evident that Tigran has become aware that he is being watched. A couple of scenes in which Tigram, amidst his own happy family, looks directly at Charlie in his own window. Not only does the guard not report him, but he is able to send through the callous guard who brings Charlie his meals an occasional treat. Even this guard, who had been scornful of the “Amerikatsi,” softens his attitude toward his prisoner. The film shows that even in a brutal system of cruelty, a small shoot of humanity can grow, and if not flourish, then at least survive enough to save a man’s sanity.

Viewers will enjoy the climax of the film, and possibly, like many critics, compare this film to Roberto Begnini in Life is Beautiful. Michael A. Goorjian does inject touches of humor into the plot, but his is not as fanciful a film as that of the Italian’s. The brutality of the Soviet system is depicted in a far more graphic way than the Nazi system in Begnini’s, so this is not a film for young children to see.

Charlie is not a praying man who would be familiar with the Psalms, but Psalm 142 is one of several Psalms that could apply to him and his situation. Also, the delightful conclusion of the film could well be expressed by Psalm 126, believed to have been written when the Jews were freed from their Babylonian Captivity and allowed to return to their beloved Jerusalem. The climax of the film coincides with last verses of this jubilant poem:

Restore our fortunes, O Lord,

like the watercourses in the Negeb.

May those who sow in tears

reap with shouts of joy.

Those who go out weeping,

bearing the seed for sowing,

shall come home with shouts of joy,

carrying their sheaves.

Psalm 126:4-6