Introduction to My Freedom Summer Journals

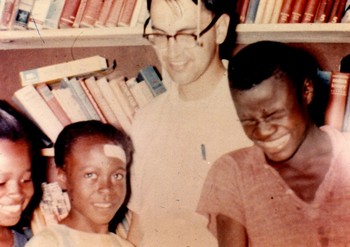

As a journalist, educator and life-long film critic, I have been fighting this particular battle for truth over many decades. My own experience in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer eventually reached a national audience because I was among the outspoken critics of the 1988 thriller, Mississippi Burning, starring Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as a couple of FBI agents who headed South to solve three of the murders that summer. The majority of established film critics initially praised the movie. It was nominated for seven Oscars and won for Best Cinematography.

I stood with the minority of critics who decried the impression that film gave of Whites swooping into the midst of largely helpless southern Blacks—on behalf of three white young Northerners who were killed that sunmer. And I was not alone. Families of the three slain young men said the film was unfair for various reasons. Coretta Scott King famously said of the film: “How long will we have to wait before Hollywood finds the courage and the integrity to tell the stories of some of the many thousands of black men, women and children who put their lives on the line for equality?”

In one of my nationally published columns, I wrote in part:

I participated in Mississippi’s Freedom Summer—and my memories of my brief time among incredibly brave people are fresh as ever. They provide a very different picture of the events in the summer of 1964 from those depicted in the movie Mississippi Burning. I am writing partly to offset the view fostered by the movie that during that summer all Mississippi blacks cowered in fear after the murder of the three civil rights workers and that it took the valiant efforts of white FBI agents to rescue the hapless blacks from the KKK reign of terror.

What kept my memories crystal clear was the journal in which I tried to write each day we were in the South—although some days were so full that I was too exhausted to write. Now, 60 years later, I am sharing these journal entries publicly as original source material for anyone trying to fairly and accurately understand the complexity of what unfolded in Mississippi in 1964. I will be correcting some original spelling errors, and I also will add a few more contemporary reflections, but I will distinctively mark any additions.

Geography is not a determinant of racism

In introducing my story from Freedom Summer, I always want to make clear that neither in 1964 nor today have I looked down upon the white Mississippians standing in the way of equality for what were then called “Negroes.” As a Hoosier, born in Indianapolis, I was raised by parents who were just as prejudiced as many white Mississippians. By example they taught me the “N” word before later they showed that in the company of others “Colored” was the proper term to refer to our “inferiors.” By the grace of God I was led out of this sad state by a preacher, science fiction, and the experience of meeting close up a few African Americans as I was growing up. This series about 1964 is not the time to explore my autobiography, but I am forever humbled to realize that—had it not been for those liberating experiences—I might have grown up into one of the many harsh White opponents of Freedom Summer.

My burning bush was a mimeographed letter

In 1964, the Rev. Roger Smith and I were pastors of churches in Bottineau, North Dakota, he of the Methodist, and I of the Presbyterian Church. A few months earlier each of us had received a mimeographed letter from the National Council of Churches urging pastors to consider giving up their vacations that summer to join the hoped-for 1000 students who would be working in the Mississippi Summer Freedom Project, sponsored by the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO)—an alliance of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; the Southern Christian Leadership Council; The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; and the Congress for Racial Equality.

A mimeographed letter was no burning bush or shaking of the foundations of the temple, as respectively Moses and Isaiah had experienced, but still, God does move in mysterious ways.

I wanted badly to go.

Although my wife Sandra was sympathetic, we did have four young children, so we agreed to think and pray about it. Then came the Sunday worship service when God spoke in another way, through a social justice hymn, so that after the worship service, Sandy asked me if I got the same message while singing it that she did–that I should go. And so she gave up our vacation for that year to free me up for the Project while she coped with 4 very young children at home by herself.

One day Roger asked me if I had received a letter from the NCC as he had, and to our mutual surprise we discovered that each of us had signed up. He made a few adjustments in his dates so that we could travel together in our family’s station wagon.

Thus at 6:30 AM on Monday, August 3, we left Bottineau in our family station wagon, both of us praying for a safe journey and for courage and patience “to meet whatever comes.”

Journal: Wednesday, August 5, 1964, 10:30 PM

Note: The dates in this series refer to when I was writing.

What a day!

The hot, dusty trip with our car trouble is behind us now. The Ozarks are certainly beautiful—too bad as travelers we don’t have—or take—time to enjoy them more. As we drove around a curve, and the vista of the valley with the tiny buildings stretched out before us, I felt very close and thankful to Thee, O God. Another time I felt this when the gold of a grain field contrasted so lovely to the multi-shaded greens of the rolling hills around it. In spite of the poverty, Arkansas and Missouri are blessed with wonderful scenery.

As we drove through the Arkansas night, we listened to the somber voice of the President (Johnson) explaining to the nation the action he was taking against North Vietnam in retaliation for the boat attacks. Shortly after this we were on the bridge crossing the Mississippi into Vicksburg. At that moment the news of the identification of the 3 bodies found by the FBI was broadcast.

Fitting news for entrance into the Citadel of Segregation!

Both of us wondered aloud what lay ahead for us as CR workers.

Short as the ride is from Vicksburg to Jackson, it seems long if you’re not an ordinary tourist—especially at night. It’s a strange feeling, to feel as if you are in enemy territory in your own country, but we both felt this way. Doubtless due to the preconditioning of our minds from all the press and magazine accounts of Mississippi.

No incidents or problems—other than staying awake the last few miles.

Our motel—the Sun-N-Sand—is certainly a fancy one with a heated pool, restaurant, TV, etc. And integrated! Right here in Jackson! As we learned from Warren McKenna (NCC staffer in Jackson), this is a fairly recent development, thanks to the C-R law. Who says laws such as this don’t help?

They should be grateful here—Civil Rights hasn’t hurt their business. Warren tells us that the motel has received over $30,000 for food and lodging from the NCC & COFO workers and lawyers. Not too bad. Yankee money seems readily acceptable, if not Yankee ways.

This morning began auspiciously. We were eating breakfast when we heard a call for Warren McKenna announced. Warren was at the table next to us, so we were able to meet him and get directions to the NCC Office for our later meeting.

Upon our arrival we received a folder of materials and forms to fill out. The office itself was quite shabby and run down—but not the staff, with phones constantly ringing, typewriters clacking. Warren started off our orientation by telling us about NCCs involvement. It seems that the Mississippi Summer Project is COFO’s with the NCC helping to “service it”—which sheds some light on our role as minister/counselor.

Journal: Friday, August 7, 1964, 8:15 PM

While the NCC office at Jackson is in an old building are terribly run down and shabby—the offices certainly are suitable. Their very shabbiness reflects that this is a movement of the people and for the people—very little if any support from the wealthier class—they’re too busy supporting Goldwater or the Birchers.

Our Wednesday orientation continued with a workshop on Non-Violence led by SNCC.

(The original journal breaks off here due to an interruption at the Freedom Center where I was writing. I left three pages blank in the hope of going back and filling this in. Our time was so filled with activities that I never did.)

We went from the NCC office to COFO’s office, ironically located on Lynch Street. It was easy to tell which office—the only storefront that was boarded up with plywood. Twice bricks thrown by white toughs had shattered the plate glass window.

The second time it was decided to forget about replacing the glass. COFO was a fantastic place—people coming and going—typing, answering one of the dozen telephones that linked the Center with the many Freedom Centers around the state.

We had been told that we were going one place, but then this was changed when it was learned that Shaw was losing its minister and a couple of other Northerners whose vacations were ending. Although we never got to meet him, we knew that the leader of COFO was Robert Moses—and, as do many of the Blacks, we enjoy the symbolism of that last name!

We were given a quick run-down of Mississippi customs and law.

We must obey all traffic signals and speed limit signs and remember to always stop at RR crossings. No locals paid attention to this old law—but it was a favorite excuse for the police to catch the CR workers and part them from their scarce money. We were told to demand that we be able to make our phone call if arrested, which should be to one of the Freedom Centers or to Jackson. This was impressed on us in the light of what had happened to the CR workers who had been arrested and murdered earlier.

Then we were told, “When you are convicted…”—not “if” but “when”—the arrested CR worker could expect no justice, just a conviction. There had been the case of a Baptist minister having been arrested and charged with drunkenness, despite his having been a lifelong teetotaler.

We were especially impressed with the young black man who led the non-violence workshop. He told us if we had a gun or knife we should give it up or leave Mississippi. We could not be of any help to them if we felt we needed a weapon. He urged us to keep calm if we were surrounded and never to answer back with insults or in a way that showed that we were afraid. We practiced, after watching him, rolling into a tight ball to protect our stomachs, faces, and private parts. Later we learned from others that this was no academic subject with him. He had been arrested for his CR work and sent to the infamous Parchman State Prison where he had been singled out by the guards, hung by his hands and beaten.

After such a sobering day it was great to be able to go to the little church where Pete Seeger was giving a concert. One of my favorite human beings, Pete Seeger held us enthralled with his freedom songs and stories. We had to stand up, the church was so crowded.

Even though the temperature was above 100—no one left early.

What a privilege to get to meet and thank him for such a magic evening!

Please continue to watch www.ReadTheSpirit.com online for each weekly issue in August for links to more parts of this series.