I was humbled and blessed by publisher David Crumm’s tribute to me this past week. He has such a distinguished career in journalism that such praise coming from him is especially appreciated. Since its founding in 1990 Visual Parables never has grown to become a major journal, but it has drawn a small group of loyal readers who on occasion let me know it has been useful in their ministry, but never so powerfully as David’s.

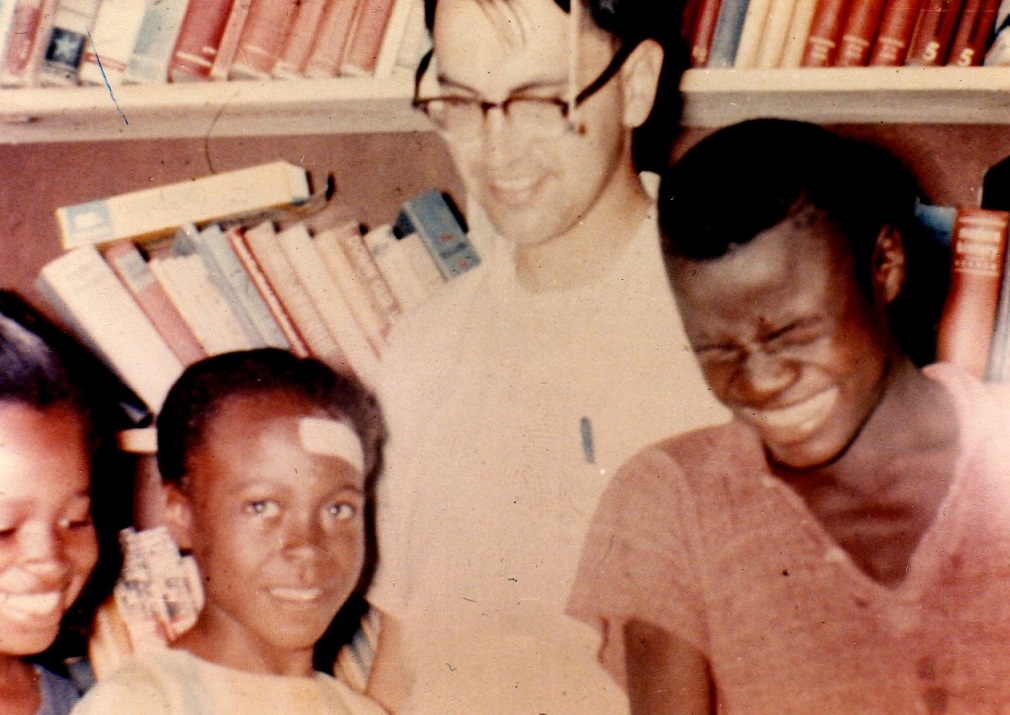

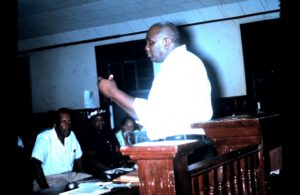

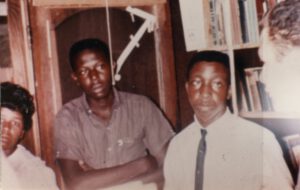

David, in words and the picture used, highlighted my involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and so I want to add a bit to this. The picture he used shows 3 children & me in the make-shift library of the Freedom Center in Shaw Ms. in 1964.

The coalition of C-R groups that sponsored the MS Freedom Summer Project rented old houses in about 26 MS counties as the basis of operations for us volunteers. One room was devoted to a library for donated books; another for relaxing & holding meetings; & a 3rd for a communications center. The latter was equipped with a telephone (very few “Negroes” could afford one), at least one typewriter, and a mimeograph or hectograph machine, plus office supplies. There were 10 or so Northern volunteers working at Shaw, but we slept elsewhere in rented quarters. (You can read my description of this in one of the series on the MFS on this blog site).

For most of a day children came for various programs or just to hang out.. One of these is the boy on the right, whom we knew as Junior. He became my shadow, and as you can tell by the photo, he was mischievous. Here are a couple other photos of him. In the 3rd photo Junior is standing in front of our Freedom Center.

I am highlighting Junior because, though just a Jr-Hi student, he was typical of the youth we met, often more active in the Movement than their parents, who had so much to lose–their jobs, reputations (with whites), and in some cases, their lives. These pictures are bittersweet because this lively kid was shot by the police a year or so after we whites left Shaw. Many of us kept in communication for a couple of years after we returned North, and it was one of their letters that informed me of his death. Very few details, just that the police surrounded his house, setting it afire, and then shooting the family.

It is such incidents as the above that prevent us volunteers from regarding ourselves as heroes or white saviors–and this is why I have always hated the false film Mississippi Burning. The real heroes were people like the Carter family in Shaw, who often fed us some of the best fried chicken we had eaten. The Carters never became well known, like some of the other African Americans I met, such as Amzie Moore and Fannie Lou Hamer:

But it was such unknown folks as them that formed the backbone of the Freedom Movement. And especially their youth. Shortly before I joined them that hot August the youth, who usually were enrolled in high school during the summer, so that they could be let out to help harvest the cotton in the fall, went on strike after their principal had ordered them not to associate with “those outside agitators.” Thinking he was punishing them, he ordered he school closed, which freed them (or their parents) from any charge of truancy, thus giving us dozens of willing volunteers for such chores as distributing leaflets.

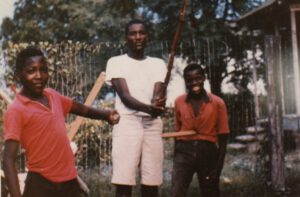

It was the youth who kept pushing for more confrontational action than adults going up to the courthouse to try to register to vote. This was against COFO (Consolidated Federation of Organizations, consisting of the major national C-R organizations) policy–it was narrowly focused on voting rights. However, pushed by the students, our director sought & received permission from COFO in Jackson for the students’ desire to integrate Shaw’s Public Library. Our staff put the volunteers (only boys were chosen, to the girls’ dismay, because of the possible danger) through training in nonviolence and even specific book titles to ask for. Dressed in their Sunday best, the brave boys ventured into the exclusive white province of the tax-supported library. The local law authorities were notified of our intent, this always being a basic tenant of the C-R Movement, going way back to Gandhi.

I was scheduled to drive a couple up to Cleveland, the county seat, where my passengers would try to register to vote, so I saw just a bit of the action as we drove through Shaw’s main street. On one side was the library wherein the boys found all the chairs removed. Up the street we spotted the black bus which had brought state troopers to town. Across the street were the white-helmeted troopers holding back a large crowd. From the brief glimpse of their faces seen as we passed slowly down the street, I could tell they were not very happy.

When I later returned, I took the picture below of one of the proud youths, with a book he had successfully taken out. They were not allowed to sit and read, but the librarian did grudgingly allow them to sign up for a card and take home the book they requested.

When I write that we whites did not consider ourselves as heroes, this is not false modesty. I was threatened a couple of times–at a gas station when they saw that I had African American youth in my car, and on a country road when I was driving youth distributing Freedom flyers to plantation workers–but never beaten up or arrested, like so many others had been. (A friend back in ND jokingly said, upon my return, that he was a bit disappointed that nothing so dramatic had happened to me.)

Along with emerging unscathed, I have to admit that I never helped add to Mississippi’s list of voters. All my passengers failed the slanted test. It was only after Pres. Johnson prompted Congress to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act did the number of Black registrations explode, allowing them to elect so many local Blacks to political positions. But still, I believe that we did accomplish something, that our sweaty time that summer had been well-spent, we benefitting more from the experience than the people we sought to help.

What we did accomplish you could call a mission of presence. Black college age volunteers (mostly members of SNCC, Student Nonviolence Coordinating Council) had been working on voter registration for a couple of years before we came. They had run up against a wall of violent resistance, beaten and jailed with the federal government refusing to protect them. Northern journalists, with perhaps one or two exceptions, took no notice of them–they were Blacks, and thus considered of no account. Only when SNCC, after heated debate, decided to invite white college students to the state, did the press, and then at last, the Feds, take an interest in Mississippi Black’s battle for the ballot.

As I report in my MFP journal, my companion from ND, the Rev. Roger Smith, and I derived the most satisfaction from what two elderly Black ladies said to us at the end of the celebration held on the eve of our return North. Each, in her own way, thanked us for coming down and said, “You opened our eyes. Now we realize that things don’t have to stay the way they are. We won’t live to see the coming Freedom, but our children will.” And so they have–though not yet fully. There is still much to be done.