Hmong communities illustrate the importance of swing voters in the 2024 presidential race

By JOE GRIMM

Director of the MSU Bias Busters project

Suddenly, after years of invisibility in American culture, Hmong Americans are popping up in news stories all summer long—including this new July 29 profile of Olympic gymnast Sunisa “Suni” Lee in The New York Times that briefly touches on traditions that are common in Hmong families. Now, most Americans have seen media coverage of Suni Lee, because of the massive global interest on the Paris Olympics.

What’s new in this wave of media attention on the Hmong is the appearance of the Kamala Harris presidential campaign in full swing—which means her allies are working to solidify every possible connection the candidate can make with swing voters nationwide. And that includes the potential of electing the first Asian-American president. Among the headlines exploring the Asian roots of Harris’s family is this July 28 New York Times story by Amy Qin, which points out how much Americans still need to learn about her background.

No, Harris is not Hmong, but keep reading because complex cultural connections are popping up every day and there’s more about Harris and Hmong Americans below.

So much to learn! That’s why we’ve published so many books!

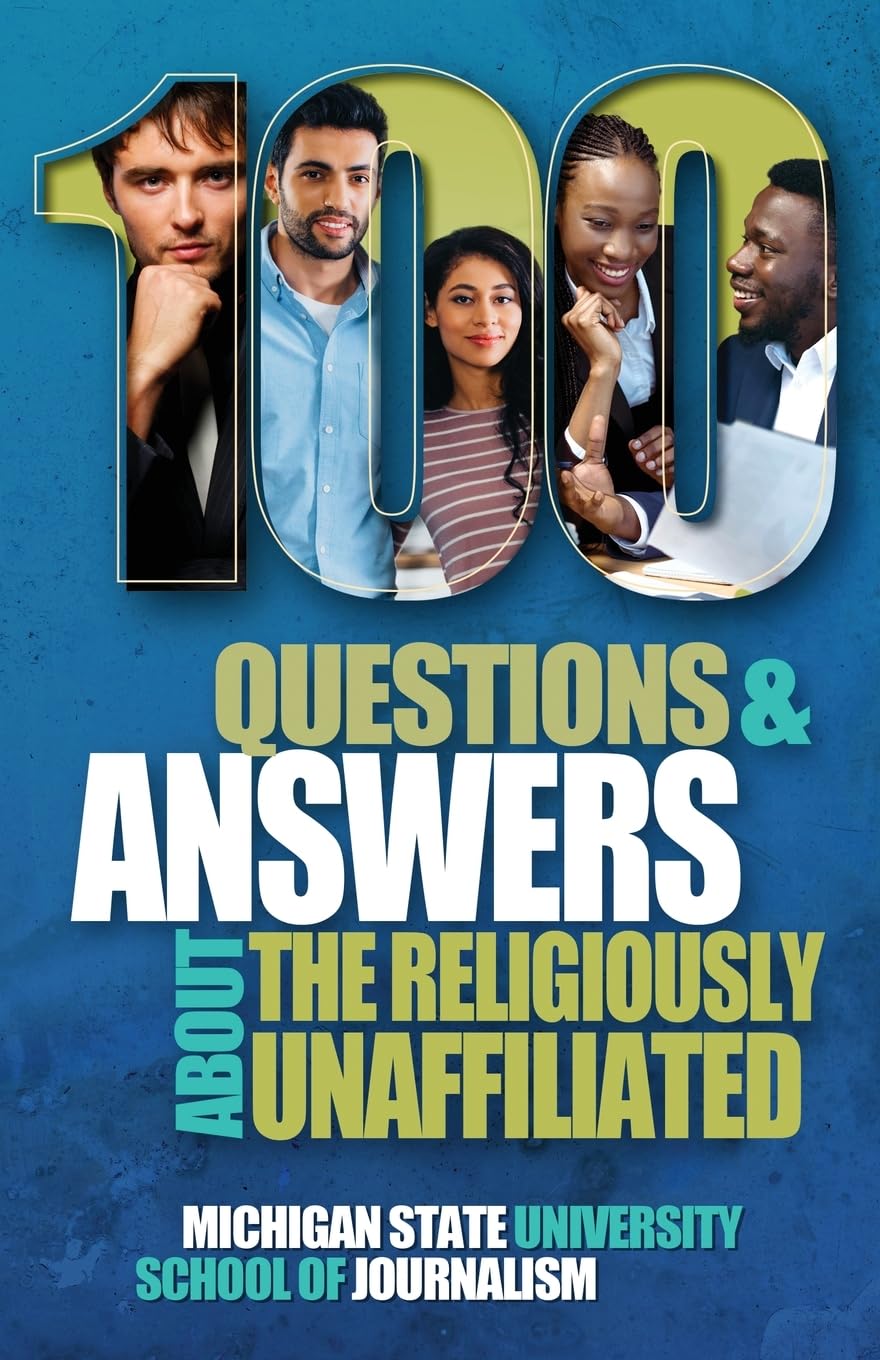

This summer, everyone connected with the MSU Bias Busters project is eager to spread the news about our books on American diversity—prepared by Michigan State University School of Journalism students who have been advised by blue-ribbon panels of experts nationwide. Working with those panels of leading figures from these communities to insure accuracy and balance, the students’ nearly two-dozen books now include at least a half dozen volumes that are relevant to these two stories about Lee and Harris that are dominating news cycles as August begins.

- 100 Questions and Answers About Immigrants to the U.S.

- 100 Questions and Answers about Hmong Americans: Secret No More

- 100 Questions and Answers About East Asian Cultures

- 100 Questions and Answers About Indian Americans

- 100 Questions and Answers About African Americans

- 100 Questions and Answers About The Black Church

And—with each day’s news headlines—the list of the relevant-right-now books in this MSU series quickly expands beyond that half-dozen titles.

Why is that?

These distinct communities are connecting with each other every day!

On July 21, Kamala Harris clinched pledges from the majority of Democratic delegates who will nominate the party’s candidate for president. On July 23, her campaign team and surrogates were working the Hmong Village Shopping Center in St. Paul, Minnesota.

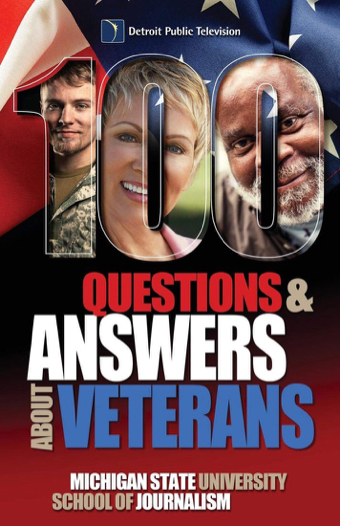

That quick turnaround illustrates how much attention candidates and parties pay to voting blocs, even small ones, in swing states where fewer votes can make a difference.

Harris could become the first Asian-American president. Her mother is Indian and her father is Jamaican.

Hmong voters, who number only about 300,000 nationally, are the largest Asian group in Minnesota, a key battleground state in the 2020 election. Speculation about whom Harris will choose as her running mate has included Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz.

Additionally, Hmong people have among the highest rates of naturalized citizenship and voting of all Asian Americans. They were airlifted from Southeast Asia during a brief window starting in 1975 by the United States. We developed close ties with their communities because we had recruited them as allies in the fight against the Viet Cong in Southeast Asia.

Mai Xiong, who runs a produce store at the St Paul shopping center, said many people she knows support Harris—not for her gender or ethnicity, but for her experience. Harris “will get a lot of Asian votes,” Xiong told Sahan Journal. The digital news site focuses on Minnesota’s immigrants and communities of color.

Clearly, however, political activists are hoping that an Asian-American ethnic connection may prove persuasive in November. Although Hmong Americans live in all 50 states, their populations are highest in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan—swing states all—and California, where Harris is from.

To illustrate that importance of those cultural connections—a speaker at a St. Paul roundtable was Cincinnati’s Asian American mayor, Aftab Pureval. He grew up in India, and his mother was born in Tibet.

Sahan Journal reported that Pureval said, “You might be wondering, why is the mayor of Cincinnati here in the Twin Cities? It’s because we have an opportunity to elect the first auntie, the first Asian American president in our country’s history.”

100 Questions and Answers About Hmong Americans: Secret No More, was published in July. It addresses the Hmong journey to the United States, their high rates of naturalized citizenship and voting. For an easy overview of the entire series, simply visit MSU Bias Busters project at Amazon.