Three key people behind this new public TV documentary, Healing Hate, are from left: Sunayana Dumala, Solomon Shields and Mindy Corporon.

“Hate has no place—because it will touch everybody.”

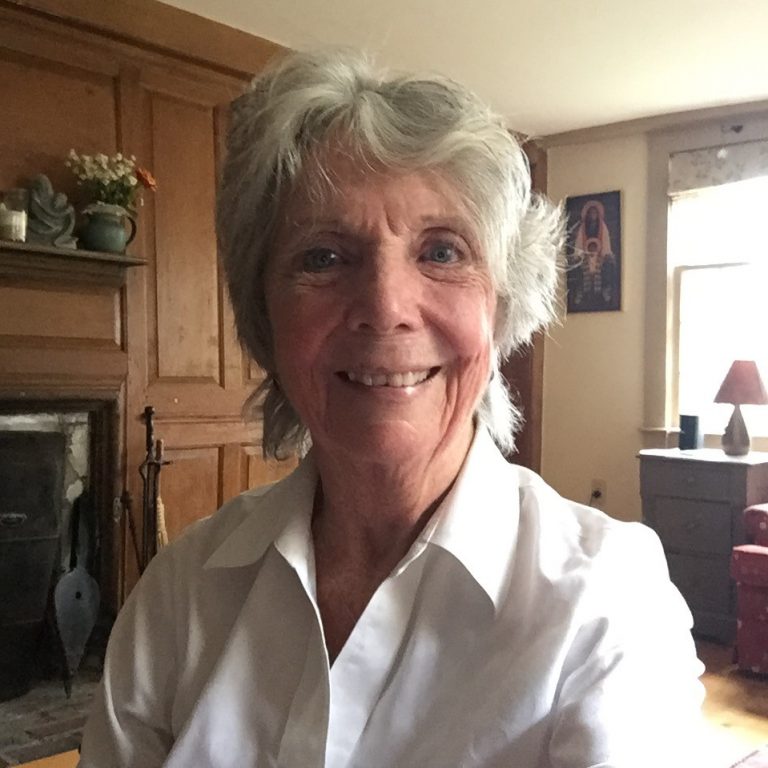

Mindy Corporon in the documentary Healing Hate

“But both Mindy and Sunayana and their families used the worst days of their lives to empower them to engage the world in positive ways.”

Documentary filmmaker Solomon Shields

See this powerful documentary right now:

Right now, you can learn more about this documentary, created by Kansas City PBS along with filmmaker Solomon Shields, by reading our ReadTheSpirit cover story below.

But, first: Thanks to Kansas City public TV’s YouTube channel, you also can stream the entire half-hour documentary here:

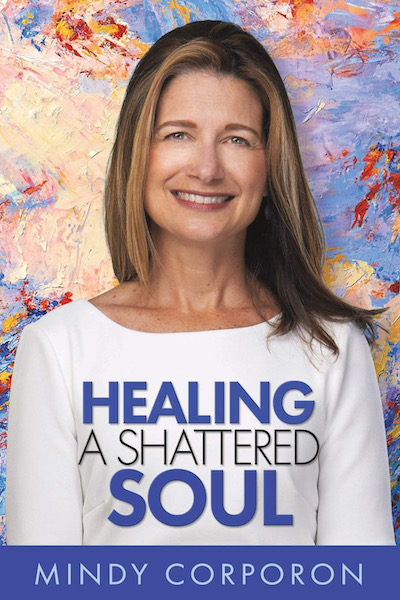

To read Mindy’s entire story, including how she met her friend Sunayana—get a copy of Healing a Shattered Soul in hardcover, paperback or Kindle via Amazon.

‘Healing Hate: Turning Pain into Power’

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit online magazine

After weathering some of the most horrific hate crimes in America over the past decade—including a catastrophic mass shooting at a parade in February—Kliff Kuehl, the CEO of Kansas City’s PBS station, and filmmaker Solomon Shields committed themselves to arousing public action.

As the resulting 30-minute film debuts this week, Kuehl is telling viewers, “Kansas City PBS is honored to bring Healing Hate to our viewers. This documentary has the potential to inspire and ignite a collective commitment to stand against hate, fostering a more inclusive Kansas City,”

The film’s power springs from the stories of two women who have transformed their grief over losing family members, killed in earlier shootings, into major ongoing efforts to promote compassion, healing and inclusion.

The first of these two friends is author and nationally known advocate for community compassion Mindy Corporon, whose son and father were killed 10 years ago in an antisemitic hate crime outside the Overland Park, Kansas, Jewish Community Center in 2014. Mindy has published the widely read memoir Healing a Shattered Soul and also is co-founder of the nonprofit community movement known as SevenDays.

Mindy’s friend is Sunayana Dumala, who Mindy met in 2017 after national news broke about the murder of Sunayana’s husband by a shooter in an Olathe, Kansas, restaurant. The murderer declared that he wanted to kill someone from the Middle East—and that he thought his victims were Iranian.

“I worked a lot of long hours with Mindy and Sunayana and many others on this project because all of us know how timely this documentary is,” Solomon Shields said in an interview this week.

The urgency they all feel this spring includes the latest mass shooting at the Kansas City parade—as well as national reports that hate crimes are rising to an all-time high, plus the upcoming April 13th 10-year anniversary of the antisemitic shootings that killed Mindy’s loved ones.

“All of us felt we had to share this documentary with as many people as possible—right now,” Shields said.

What’s so horrifying is: When bullets fly—they can hit anyone

“What’s so astonishing is that in all three tragedies—the gunmen were coming from a place of anger and violence that wound up killing people who they never intended to kill,” Shields said. “That’s one of the main themes of this documentary: When bullets fly, they can hit any of us.”

In 2014, Mindy’s son and father were in a parking lot preparing to participate in a community program being held inside the Jewish center—but they were not Jewish. In 2017, the shooter in Olanthe was raving about Middle Easterners and mistook Sunayana’s Indian-American husband for an Iranian, according to news reports. And, in February 2024, the one death and 22 injuries were caused by several armed young men who opened fire at each other in a personal dispute that had nothing to do with their 23 innocent victims.

“We have to realize: When guns are blazing and bullets are flying, those bullets don’t care what you look like or who is waiting for you at home,” Shields said. “It’s so important for people to understand that we all must take steps to prevent this from happening to others.

“This is definitely something that hits close to home for me as an African American filmmaker,” he said. “I have had friends who have lost their lives to gun violence: wrong place, wrong time and a bullet happens to hit them. I was very honored to work on this project because it’s something I can relate to. I remember both of these earlier shootings and they had a real impact on me.

“The main theme of the documentary is how these two families overcame such unspeakable tragedies so that they could continue to live and build relationships. That’s the flip side of this documentary: Even after such tragedies, we can decide to build relationships that can make our entire community better.

“I am so impressed by the strength of the human spirit in these two women who were able to face the world again after the worst days in their lives,” Shields said. “For a lot of people faced with this—it would have been understandable to simply say: We need our privacy and refuse to talk to anyone anymore. But both women and their families used the worst days of their lives to empower them to engage the world in positive ways.”

That took an enormous amount of emotional strength within these families—as readers learn when they read Mindy’s memoir. In this new public TV film, viewers also will see and hear these two friends talk about that process of transforming anger into hope.

Shields said he continues to be amazed at their strength. “I realize that they may not ever have a perfect day again after such tragedies—because every day they will remember the loved ones they lost. That’s why this film is so inspiring. These women chose not to close themselves off to the world. They decided to show the rest of us that there is still life worth living, if we can work on these issues together.

“When people see this documentary, I want them to come away, first, feeling informed about all the reasons this is such a timely message. Second, I want viewers to feel inspired that, even though these horrible things continue to happen, there are relationships we can form that can help us, our families and our communities—that is, if we are willing to search for those new relationships.

“Finally, I want people to feel that there are things they can do whoever they are and wherever they are,” Shields said. It’s a lesson he took to heart as he worked with these families and the Kansas City PBS staff to produce this film. “That’s what I could do right now. I’m a filmmaker here in Kansas City and I did something: I created this documentary that can share this story with so many people out there. And, now, I appreciate that others are out there trying to encourage more people to see this film.”

And one last reminder …

Wherever you live across the U.S., you can contact your local PBS station and urge the management to seek out this documentary to broadcast in your region. If you have never done this before—simply find the website of your “local” PBS station, contact station management through their website and share a link to this story. Most public TV stations appreciate local viewers making such recommendations.

To read Mindy’s entire story, including how she met her friend Sunayana—get a copy of Healing a Shattered Soul in hardcover, paperback or Kindle via Amazon.