EDITOR’S NOTE: In February, we published a column by Rusty Rosman that posed the question: “What will you wear when you’re dead?” The question went viral. Many readers responded, telling us that they started asking friends and family members this unusual question. Rusty’s purpose in asking that question was part of the overall process she describes in her helpful new book, Two Envelopes. The book guides readers through making notes for their family and friends about their wishes, when they die someday. The most elaborate and eloquent response to the provocative clothing question was this column written by long-time professional communicator Barbara Braver.

By BARBARA BRAVER

Contributing Writer

The “larger life” here has nothing to do with moving to a larger clothes size. The idea of the “larger life” comes later in all of this, as does the silk blouse. Meanwhile, I am remembering Mother with great affection, nearly four decades after her death at age 83.

There are things we remember, and things we choose to forget. In this moment I am thinking of something I most definitely have not forgotten, but to which I have ceased to give power. That is Mother’s critical nature, which was more than matched by that of a beloved aunt, Mother’s sister Catherine.

With regard to the silk blouse: it was such an elegant gray silk blouse of Mother’s that though I am, of course, using American spelling, I think of it as a grey blouse. The English spelling seems somehow grander and more fitting for this particular blouse. In any event, the blouse is the end of the story—the end of the earthly story for Mother as she was buried in it. But, I have skipped to the end, which will only make sense if I start a bit earlier.

Now that I have raised children of my own to adulthood, I have an increasingly clearer sense of the mother-child connection and the positively frightening potential within that bond for both good and ill.

In the case of Mother, my wild Irish mother, it was mostly expressed for the good. Of course, time has dimmed what was painful or unpleasant. In fact, since her death all ill feeling has fallen away. She has been totally rehabilitated, if not actually canonized. Also, I have come to understand better some of the relational pieces, which required years of life experience, illuminated by therapy.

I am not now who I was then, and neither is she.

It is unlikely that my now lost blue diary from the 7th grade included any reference to my struggles with Mother, little fits and starts, and thrust and parry, and hug and kiss and each then feeling sorry for what we had thought or done, as the naughty child or the imperfect mother. Nor would I have written anything about her struggles, of which I knew little, at least not at an available level of consciousness.

I knew she grew up with Catherine, her bossy little sister who was younger by less than a year. “Irish twins” they called such close-in-age siblings. And they certainly were Irish, both of their parents having made their way from there to live in Sewickley, Pennsylvania. Catherine knew-it-all, or had the façade of one who did and was always eager to share her superior knowledge in bold terms followed by the sort of tic of the dismissive laugh. Catherine was the master of dropping an “Oh you may not care about this, but you ought to—” And, of course, I have no sense of what her interior life was all about.

I knew that Mother’s brother, Jim—“our Jim,” the youngest of the three—was an important lawyer. That’s the way I would have understood it: an important lawyer. With money. Discretionary money enough for Sunday ice cream for me and a convertible for him. I knew Uncle Jim had a fine education. His law school graduation day photo is mounted on one of the crumbling black paper pages of our ancient leather-bound album. He smiles out from under his mortar board, his lanky 6’2” frame hidden under his gown. Catherine is in the middle next to him, also smiling.

Is it my imagination that Mother seems more like observer than participant on this day of celebration? Her body is half turned, as if to look less bulky—in a ¾ view. But, Mother was not at all bulky and how often she told me that at 5’6”, a height tall for women in those days, she “never weighed more than 118 pounds”—a weight I have not had since I was—say 12. She is held there in that photo, young and posing at the edge of her vulnerability.

Our Jim got the education in the family. At least that is what I used to think: he “got” the education. Then I found out that was only half true. Yes, he went to college, as his sisters did not, but he did not graduate with his class. Though his course work was finished, his tuition bills were not paid. How can this be? Grandfather— PapPap as I, his first grandchild, had named him—PapPap had come from Ireland after college and through wit and charm and hard work had made what then was lots of money, or so it was said. Daniel Francis Dillon, who could “charm the skin from a snake,” owned three houses when he died. That was the script. It was also said of him that “he could not smell the cork.” PapPap was a “ward healer”—working for the party, getting votes for his candidates. I can imagine a drink bought here and there, and another, was a part of that. I know that Uncle Jim had a highly successful ongoing law career, but I am sure he had his own feelings about all of this, of which I am not aware.

Mother and Catherine, equally bright, equally eager I feel sure, in line with some of the prevailing cultural norms of those days, did not go to college. Rather, they went on to work at the telephone company, a respectable temporary destination for them until they were swept up into marriage and the life expected of each of them.

Given all of this history, my biggest realization, and I know this sounds obvious, is how much Mother identified with my triumphs and failures. Worse, she felt responsible for them in large measure, which gave her an enormous energy, more than I wanted, around all of my doings, most particularly those having to do with outer appearance. The look of things, including her only daughter, mattered to her a great deal, and her intensity likely propelled me into a rebellious rejection of her particular standards of taste.

Things went pretty smoothly between us in my early years before I developed any opinions contrary to hers. By the time I was six or so I had to be stuffed into the pink sweater that matched the pink pinafore. I can dredge up certain phrases of hers, questions tentatively phrased but with a quite explicit subtext. “Do you think that looks alright?” “Don’t you think plaid makes you look fat?” “Are you planning to wear that?” (Well, gee, I was walking out the door in it.) “Do you want to be just as broad as Nelly’s dresser?” I had never seen the dresser of the oft-evoked Nelly, but I got the idea.

There is a certain irony in the fact that I can also hear Mother warning me: “Sins of the tongue, Barbara! Sins of the tongue.” I guess she knew what part of me would get me into the most trouble, and the same was true for her. I now know that Mother’s insecurities about her own self were operative here and that she needed me to “be somebody” as a measure of her mothering. Perhaps some of her buried hopes for herself were to be realized in me, her only daughter. Mother often said that “it takes three generations to make a lady.” I guess that means that I—following Grandmother, and Mother, was the third generation here—and the destined lady. However, going very far down that path is not part of my brief, given where I am in my life and where she is in hers.

That brings me back to the blouse. Before Mother’s funeral Mass and burial there was the “viewing,” which has always struck me as a strange term. It was the period set aside by the funeral home to give family a quiet moment with the deceased, and then friends and neighbors time to come and offer condolences, pay their respects, and reminisce about what had been. Mother was “laid out,” as they say, in an open casket, having been combed and powdered, and I don’t even want to think about what all else, in preparation. (I am planning to be cremated myself.) She was dressed in what someone, I believe my dear brother, George, chose as suitable and appropriate for such an occasion. You could only see her down to about mid-chest, the rest of her mortal remains being under some sort of a silk shawl affair.

Highly visible was the elegant silk blouse in the shade of softest gray. Affixed to it, just where she would have put it herself, was a silver pin. It was a regal lion, caught in mid-stride: just the sort of pin one finds in museum gift shops. I had seen her wearing it often. I thought she looked quite fine, for a dead person that is.

After my brother and I had a quiet moment with Mother, other family members came forward. In the lead was Aunt Catherine. I loved my Aunt Catherine and since she was not my mother, I could ignore her frequently acid remarks and opinions and just enjoy her for her wit. She and Uncle Herb had taken me in during the week when at age 4 I dealt with the reality of my newborn brother about to come home from the hospital and stay for the rest of my life. They bought me a fancy blue tricycle and explained that was what “big girls” could ride. They gave me grapefruit for breakfast, which I had never had before, and told me this was something unknown to babies. All through my little girl years I delighted in spending weeks each summer at her house, bopping around with her ever increasing number of children and making up one-finger tunes on their old upright piano.

I should note that, by the time of Mother’s death, Catherine had lost enough of her marbles—and thank heavens she had started out with lots of them—that when visitors arrived at the funeral home she greeted them warmly, thanked them for coming to her home, and directed one of her children to “please get them some tea.” At one point she spotted someone she recognized and pointed him out to me with great excitement.

“Look, that’s Joe Rafferty, I’m sure, but is it young Joe or his Dad?”

Well, the gentleman in question, erect in bearing and handsome still with his shock of white hair and bright blue eyes, was a match in age for Aunt Catherine. I was pretty sure he wasn’t young Joe.

“That must be his Dad,” I told her.

“Oh,” Aunt Catherine exclaimed, “how truly grand of him to come. He was a good friend of Father’s.”

A good friend of Father’s?

Hmmm. This would have made the fellow about 120 years old. I said, “Actually, Aunt Catherine, I think that must be young Joe.”

In any event, Catherine had not lost her grip on her fierce opinions about the appearance and presentation of everyone who crossed her path. She swept, as best she could, up to Mother’s coffin and practically hissed at me, the bereaved daughter: “How could you dress Mary in that dreadful gray blouse?!”

That really stopped me.

I looked at Catherine, unable to imagine what one could possibly say in response. And then, the moment of clarity, of joy, of illumination hit me. Mother was free. Mother had been released. She cared not in the slightest about what she was wearing. It no longer mattered to her. Her 83 years of anxious concern about what is right, proper, appropriate, suitable were over. Alleluia. I thought: that is what the larger life is about, beyond pettiness and the narrow meanness of far too many of our days, beyond the superficial.

Released!

I looked at her lying there, very beautiful really, in that elegant blouse, and felt great delight for her new state. I bent over and kissed her. I think she may have winked at me.

This was the beginning of a healing for Mother and me. Well, Mother is already there—restored, redeemed, in a place that is no place and every place.

As for me, grateful for God’s grace, I am moving toward it.

.

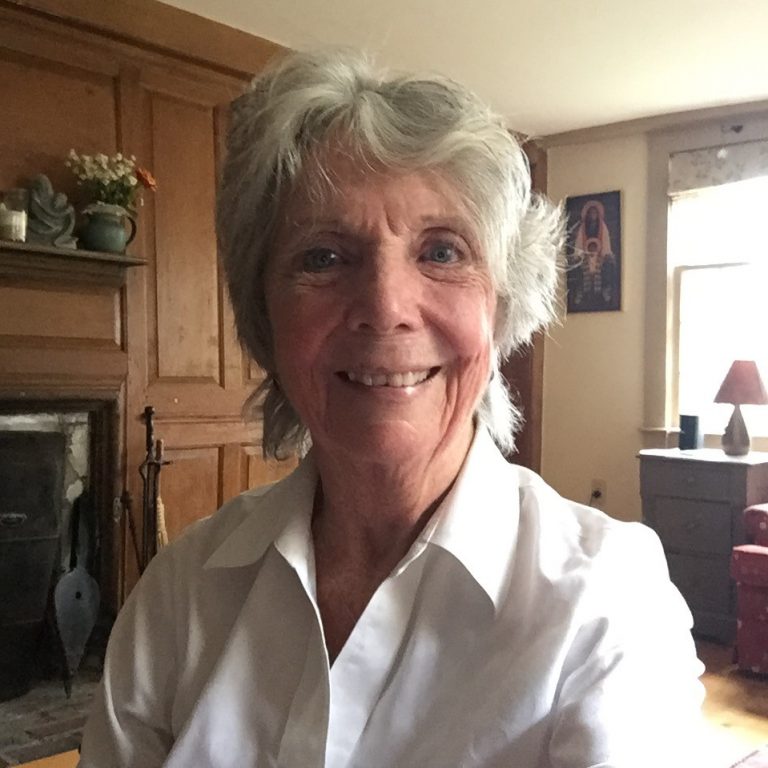

.Barbara Braver grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where at age 12 she started a one-page weekly newspaper called Neighborhood News. It lasted for a full summer, to the amusement of several indulgent neighbors. This was the beginning of the writing life. After college graduation she moved to the Boston area, drawn by romantic notions of Emerson, Thoreau and Louisa May Alcott. Though this might have been an insubstantial motive, she has never been disappointed. By an apparent coincidence she ended up working for the Episcopal Church in the area of communication, first for 11 years as Director of Communication for the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts until another coincidence sent her to New York where for 18 years she worked as the communication assistant for the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church. Since retirement she continues writing, editing and leading retreats. Barbara was also Madeleine L’Engle’s housemate for 12 of the years she lived in NYC.