Movie Info

Movie Info

- Director

- Abi Damaris Corbin

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 43 minutes

- Rating

- PG-13

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 2/10

- Language

- 1/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 1/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

You who live in the shelter of the Most High,

who abide in the shadow of the Almighty,[a]

will say to the Lord, “My refuge and my fortress;

my God, in whom I trust.”

For he will deliver you from the snare of the hunter

and from the deadly pestilence;

Attend to me and answer me; I am troubled in my complaint. I am distraught

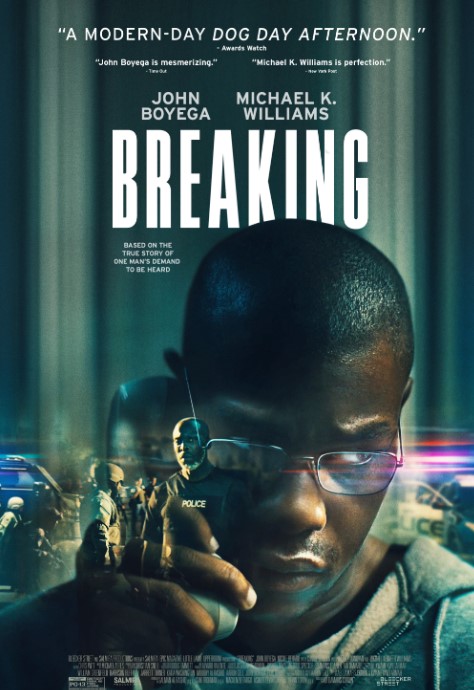

Director Abi Damaris Corbin’s tragic, heart-rending film is based upon a true story about a tragedy in Marietta, Georgia that unfolded on July 7, 2017. Based on a lengthy magazine article by Aaron Gell, the script by the director and co-writer Kwame Kwei-Armah sticks very closely to the details revealed in the article. The story of Lance Corporal Brian Brown-Easley is similar to that of many another veteran soldier, and yet very different in the sensational way that it ended in violence—needless according to the author of the article and many other experts.

The night before Easley (John Boyega) takes over the Marietta branch of the Wells Fargo bank he is making his usual phone call with his daughter Kiah (London Covington) as he walks along the highway toward his $25 dollar a night motel room. Though he had seen her sporadically since her birth, he kept in regular touch through the yellow cellphone he had bought her. They talk about the puppy he has promised her, and before he can answer her question about when he is going to pick her up the next day, his credit is up on his flip phone, so they are cut off.

The next day, dressed in a light gray sweatshirt and carrying a backpack, he calmly enters the bank, politely asks teller Rosa Diaz (Selenis Leyva) to withdraw $25, then asks for paper and pen, and writes her a note that says “I have a bomb.” The terrified Rosa signals with her eyes to branch manager Estel Valerie (Nicole Beharie), while Easley orders her to call 911. Valerie dismisses her customer and complies with Easley’s command ro send out everyone but herself and Diaz. Assuring them he means them no harm and that he does not intend to steal the bank’s money but wants only the $892 the VA owes him, he apologizes many times for the stress he is causing them.

Through his conversation with a news producer at an Atlanta TV station and flashbacks to his tumultuous visit to a VA office we learn that he is one of those countless victims of the huge organization’s inept bureaucracy and labyrinthine rules. He had been living a hand to mouth existence for many years, often sleeping in his car. During this period he was in and out of mental institution and contact with his loved ones, his main source of income being his disability checks from the VA. He had returned from his service in the Iraq War with a bad back and PTSD and other mental issues that affected his relationships with his large family and new wife— the lack of stable housing, the intermittent communication with his daughter and a guilty conscience over the promises he can’t keep.

Brian makes other calls as well, including to Kiah, and soon the area surrounding the bank is aswarm with law enforcement officers and TV reporters– dispatched to the scene are the Cobb County Police Department, a bomb squad with their remote controlled rover, a SWAT team, crisis negotiators, a K-9 unit, the FBI, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and even the fire department. The Sheriff’s Department takes on traffic duties.

Hostage negotiator Eli Bernard (the late Michael K. Williams) quickly establishes rapport with Easley by revealing that he too had been a Marine. Because he was stationed in California, Easley calls him “Hollywood.” Gaining his trust, Bernard calms Easley during some his outbursts and assures him he wants to get him as well as the hostages out alive. He tries to communicate with the heads of the other law enforcement troops, but they seem to be more interested in ending the stand-off as soon as possible than in the safety of the three in the bank. They, unlike Bernard, Easley, and the two women, are all white, but the film does not emphasize the possibility of racism, maybe because there is so much other issues. The stand-off is actually ended by a sniper, also a white man, who acts on his own initiative, even though Bernard had negotiated an exchange of one of the hostages for a pack of cigarettes.

All the principal actors contribute to the success of this stark story. We can feel Easley’s frustration and rage with his situation—when the VA clerk dismisses him with a pamphlet and in the crowded waiting room Easley breaks into a rage, he is escorted out in shameful handcuffs!—as well as the sheer terror of Diaz and the restrained fear of Valerie. The latter at one point texts a farewell message to her young son. Easley, knowing all too well how whites deal with troublesome Black males, several times in his warm conversations with Bernard, comments that he will not get out alive, that he is a dead man.

For me one of the most moving scenes in the film, revealing that Easley is a person of faith, is his last call to his daughter during which he asks her to pray with him. Holding the Bible which he has packed in his backpack, he reads the opening passage of Psalm 91—see above. This great psalm, which has bolstered the faith of so many during times of danger, is the only comfort he has, excepting the words of the sympathetic hostage negotiator.

At Sun Dance this film went by the title 892, referencing the VA check that Easley needed so badly and was so desperately trying to get back. The present title seems open to a duo interpretation—referring to the breaking point of a man victimized by a cold bureaucracy that cared nothing for him, and the “Breaking news” of a TV station where, as we see in the telephone call between her and Easley, the reporters are more interested in getting background information on him than the justice of his cause. This film, and its outcome, should be a good visual parable decrying the militarization of the police—in one scene we see them dressed in uniforms and helmet, armed with assault rifles, so that this could be a scene of getting ready to invade Kuwait or Grenada!

There is a poignant image near the end when in the wreckage at the bank Bernard picks up the packet of smokes he has just sent in to Easley. He also finds the small cross that the latter has worn around his neck. We then see the pack of Newports on Bernard’s mantlepiece, the string of the cross wrapped around the pack.

I was so disappointed that no one else was in the theater when I saw it. This is a film that needs to be seen by more Americans—let’s make that happen. Go see it with a friend or group.

After seeing this film you might want to obtain more details by reading the article by Aaron Gel, on which the film is based, “They Didn’t Have to Kill Him.”

This review is in the September issue of VP along with a set of 11 questions for reflection and/or discussion. If you have found reviews on this site helpful, please consider purchasing a subscription or individual issue in The Store.