Movie Info

Movie Info

- Director

- Rita Coburn

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 53 minutes

- Rating

- Not Rated

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 2/10

- Language

- 1/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 1/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

My heart is steadfast, O God, my heart is steadfast;

I will sing and make melody.

Awake, my soul!

Awake, O harp and lyre!

I will awake the dawn.

I will give thanks to you, O Lord, among the peoples,

and I will sing praises to you among the nations.

Then Moses and the Israelites sang this song to the Lord: “I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously; horse and rider he has thrown into the sea.

Rita Coburn’s contribution to the PBS documentary series American Masters is more than a tribute to a great American icon; it is also a delightful love story, a glorious medley of music, an historic triumph over Jim Crow, a testament to the power of faith and family, and a recognition that every great achievement is made with the love and support of many others.

Archival photographs and footage and recordings of the singer’s voice, both in song and from a number of interviews, are skillfully woven together with narrative from numerous Black singers and writers to form an easy to follow narrative that covers Arian Andersons life from her childhood in the early 1900s to her death in 1993. There have been other documentaries about the singer, but Rita Coburn had access to 34 cassette tapes of interviews made when she was getting ready to writer her memoir in the 1950s. Thus this film is different because, as the director says, “Previous documentaries centered around her life without her own voice. That’s what sets our documentary apart. Marian Anderson directly discusses her personal experiences, allowing the viewer to explore history from her point of view.” I should point out, too, that several of Ms. Anderson’s family members also contribute.

From the very beginning we see that her story is part of the history of pernicious racism, the narrator pointing out that she was born in 1897, just a year after the terrible Supreme Court decision of Plessy vs. Ferguson that made the hypocritical “separate but equal” practice the law of the land. Her family had migrated from the South to Philadelphia where they attended Union Baptist Church. She was six when her Aunt Mary persuaded her to sing in the junior choir. Her marvelous voice soon thrust her into singing solos, not just in her own church but throughout the city. How she gained in experience and skill is as exciting a story as one could imagine. When she needed further training to perfect her voice, her pastor led her church to raise money. There were many obstacles due to her race, but upheld by the faithful support of family and church she overcame them.

The editing by K.A. Miille of this series is very effective, with actors re-enacting some of the early events as we hear Ms. Anderson recounting them. There is an effective sequence about her 1919 visit to Chicago for a six-week opera course at the same time as a racist riot broke out. Under photos of the riot and news headlines we hear Ms. Anderson singing the spiritual “Crucifixion.” By bringing together scenes of the riot and such lines from the song as “He never said a mumblin’ word” we gain a fresh perspective on both Jesus’ identification with “the least of these” and with his own sacrifice on Golgotha.

The love story woven into the many scenes of stage and recording triumph (she recorded for RCA in the 20s and was the first Black singer at the Metropolitan Opera) is delightful. Orpheus Fisher had courted her for many years, but she knew that an early marriage would interfere with her concert career, so it wasn’t until 1943 that she agreed. As an architect he was the designer of their house and studio built at a farm that became their home in Connecticut. Racism even intruded there because the seller thought that Orpheus was white due to his light-colored skin, but when he discovered that Marian Anderson was the buyer’s wife, he tried to wriggle out of the deal by enlarging the acreage to 100 in the belief that Orpheus would not be able to afford the increased price—but he was wrong, and the couple lived there happily until the husband’s death in 1986.

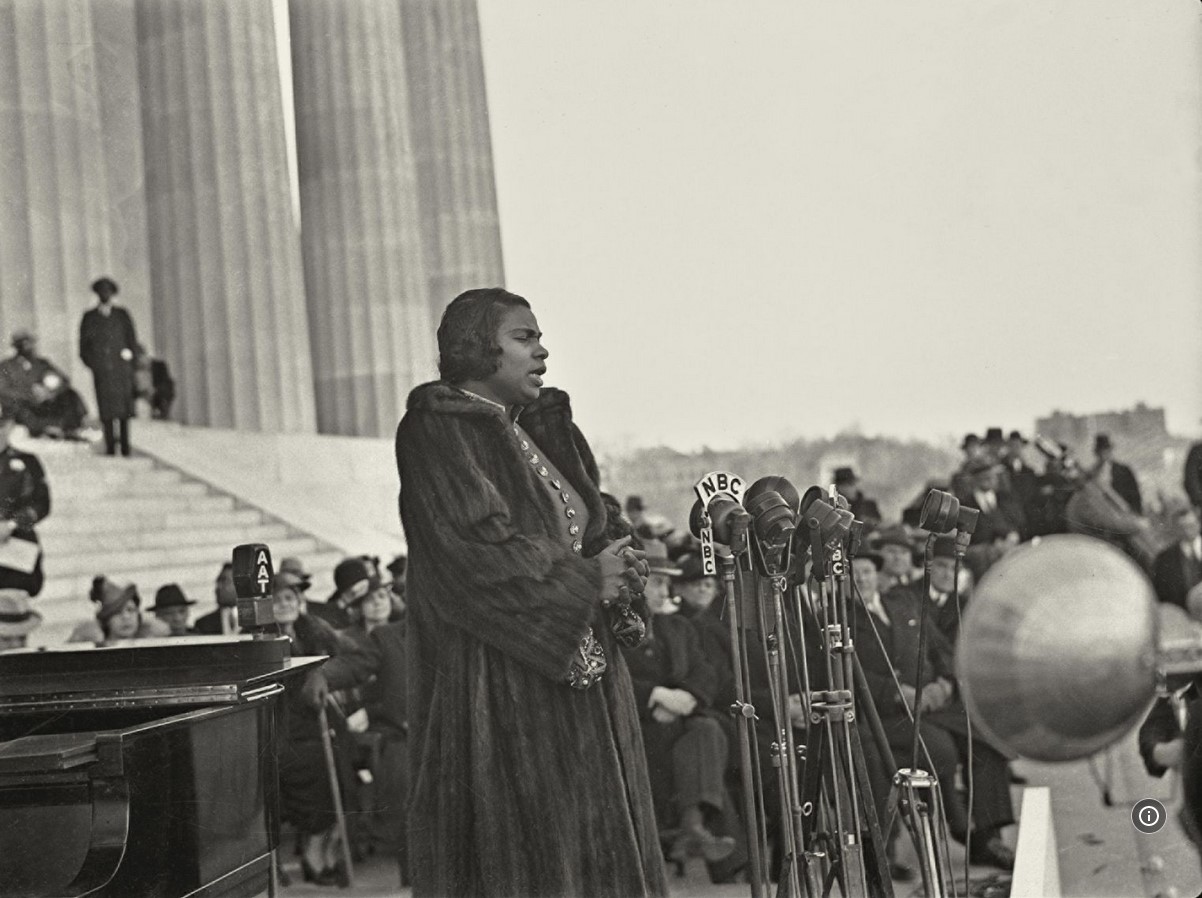

Of course, there is much in the film about the infamous refusal of The D.A.R. to allow Ms. Anderson to sing in their Constitution Hall in 1939, a story so well known that I won’t say more except to remark how teary-eyed I felt as we see her open her concert with “America,” the words “sweet land of liberty” taking on an ironic meaning. And how delightful that instead of a few thousand hearing her in the Hall, over 75,000, whites and Blacks came to hear her at the Memorial. And the bigoted ladies’ refusal had caused so much commotion, including the resignation and denunciation of their most famous member Eleanor Roosevelt, that millions more heard her through the national and international radio networks that covered the event! Talk about “in everything God works for the good”! (Romans 8:28)

And what a joy to see her singing 24 years later at the same spot during the March on Washington a little before Dr. M.L. King, Jr. delivered his great speech! One little fact I was gratified to learn was her friendship with scientist Alfred Einstein who came to her aid in 1937 when she gave a concert in Princeton , New Jersey. The scientist had come to her concert and offered to accompany her to her lodgings at Nassau Inn. When they turned her down because of her race, he invited her to stay with him, a practice that continued for the next 18 years whenever she came to Princeton.

Another hitherto unknown fact I enjoyed took place during her two years in Europe where, unfettered by Jim Crow, she sang so triumphantly in so many concert halls that she rose to international prominence. During her 30-concert tour of Finland she was able to gain an audience with that country’s national idol, composer Jean Sibelius. It was in Europe too that the man considered by many to be the greatest orchestra conductor heard her and proclaimed that hers was a voice heard “once in a hundred years.’

One more tidbit relating to racism that I did not know until seeing this film concerns the classification of Marian Anderson as a contralto, even though her range was over three octaves and she could easily hit a High C. Opera singer Denyce Graves, an Anderson admirer whose comments appear in the film at numerous points, says, “I believed that Marian Anderson was not classified as a soprano is because that would mean that she would be the love interest of a white counterpart, which was not accepted at all at the time.”

There is much more in this sumptuous biography, but you can see and hear for yourself—for free on the PBS American Masters website. I can well imagine Moses and the Israelites singing along with her, because she too rose from a low level (close to their Egyptian slavery) to that of triumph over the Pharaoh of her time known as Jim Crow. This is a film for the whole family to enjoy.

- This review will be in the April issue of VP along with a set of questions for reflection and/or discussion. If you have found reviews on this site helpful, please consider purchasing a subscription or individual issue in The Store.

- a