“From early in his legal career, Holmes emphasized that the American Republic is an experiment in self-government. … That meant protecting free speech so the strongest ideas would prevail in the marketplace, without government distortion of the competition or censorship of frightening ideas. That meant letting unions promote their interests and advocate for their members, the way capitalists could theirs. That meant encouraging evenhanded contests among all competing claims, even of unpopular defendants, and keeping entrenched interests from rigging the rules.”

LINCOLN CAPLAN in The Harvard Magazine, spring issue 2019

Review By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit Magazine

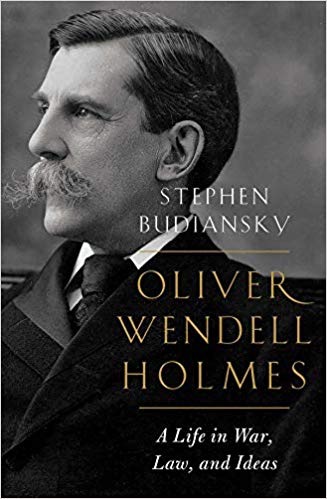

One way to describe the fascinating new biography by journalist-historian Stephen Budiansky is to say: In our turbulent era when “originalist” conservatives seem to be on the rise in American courts—especially at the Supreme Court—it’s the perfect time to remind ourselves of the great progressive Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

That single sentence could serve as an accurate review, recommending this new book to you. It’s certainly true that readers who have a liberal political agenda will find a host of quotable lines, given Holmes’ famous talents for striking metaphors in his legal opinions as well as his use of savage wit to punctuate his arguments. You’ll close this book having turned down the corners of dozens of pages, and perhaps jotted notes in the margins from start to finish.

A Convergence of Talented Writers

This book is a perfect convergence of talented writers: Holmes certainly knew how to pen memorable lines—and, as a journalist, Budiansky knows a great quote when he finds one.

Also because of Budiansky’s background in journalism, he knows how to find and then polish great anecdotes from Holmes’ life. He has sifted through the existing historical record, plus lots of letters and diaries that have not been included in earlier works about Holmes. That breathes life into these 460 pages. (The final chunk, which brings the book’s total page count to 579, are various notes and an exhaustive index.)

The Crucible of the Civil War

In Lincoln Caplan’s lengthy overview of the book for Harvard Magazine, he credits Budiansky especially for bringing to light the impact of the Civil War in shaping Holmes’ expansive view of American history—”as no author has before.” That’s certainly one of the most gripping sections of this book.

In fact, Civil War buffs will want to read this book for the more than 50 pages about Holmes’ service during that brutal conflict. He suffered a chest wound in 1861 and then a near-fatal neck wound while fighting at Antietam in 1862. Years later, at a Memorial Day observance, he said: “Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire.” Budiansky devotes several fascinating chapters to showing us what that little line tells us about Holmes’ world view.

Centennial of a Landmark Free-Speech Dissent

One way this book is being marketed in 2019 is as a centennial celebration of one of Holmes’ most important dissenting opinions. He and Louis Brandeis were the two dissenters in a 7-to-2 decision upholding the conviction of immigrants who distributed pamphlets in English and Yiddish condemning U.S. involvement in World War I.

Anarchist Mollie Steimer around the time the pamphleteers were arrested and convicted.

For passing out their literature, they were convicted under the controversial Sedition Act of 1918. That law was part of a frenzied, fearful backlash against immigrants in that era—and was repealed in 1920 when a more reasonable view of foreigners finally returned to Congress.

Holmes, of course, had been right—and his dissenting opinion defending free speech now is regarded as prophetic. Phrases from that opinion are quoted to this day. In fact, it is that historic opinion that makes Holmes such an appropriate American hero to celebrate in the pages of this ReadTheSpirit magazine.

Holmes included an acidic rebuke of the majority of his colleagues for blindly using their power to defend their own biases. Dripping with irony, he wrote: “Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition.”

Then, he pivoted to return a logical counter punch. The American ideal is not a tyranny of conservative ideas. America is at its best as a marketplace of ideas. He wrote: “When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas. … The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”

‘Catching an Echo of the Infinite’

For 12 years, ReadTheSpirit magazine has published weekly issues highlighting the best in new books and films related to religious and cultural diversity. Many of Holmes’ arguments form the American legal basis for welcoming such diversity.

Holmes was not a religious or cultural leader, but his writing often invokes a higher power—and the higher calling of his vocation. In one 1897 essay for the Harvard Law Review, he wrote this soaring description of his calling:

We cannot all be Descartes or Kant, but we all want happiness. And happiness, I am sure from having known many successful men, cannot be won simply by being counsel for great corporations and having an income of fifty thousand dollars. An intellect great enough to win the prize needs other food beside success. The remoter and more general aspects of the law are those which give it universal interest. It is through them that you not only become a great master in your calling, but connect your subject with the universe and catch an echo of the infinite, a glimpse of its unfathomable process, a hint of the universal law.

Beyond those core issues, there are lots of other entertaining passages in this book. There are gems about Holmes interacting with his prominent friends, including both the famous author Henry James and his brother, the equally famous psychologist and philosopher William James. There are compelling stories about Holmes and the women who flocked around him—partly because he vigorously defended the intellectual equality of women.

Was Holmes a Crusading Angel by Today’s Standards?

The iconic image of Holmes with his bushy mustache (from a 1970s postage stamp) that most Americans know today.

But—by today’s standards—was Holmes really a crusading angel for what we consider liberal causes?

Budiansky takes pains to say: No, by today’s standards, Holmes had some biases that we now universally recognize as flat-out wrong. The biggest example, which the author doesn’t try to dismiss, was Holmes’s easy acceptance of pre-World War II eugenics. Before the world saw the extremes of eugenics in the Holocaust, many “progressive” American scientists pushed a moral crusade for manipulating the human race. They called it “improving” humanity. That led Holmes to his infamous decision supporting the forced sterilization of inmates in mental institutions. No question: He got that dead wrong. His ruling included particularly cruel language. He was a sometimes flawed prophet. He was not such a visionary that he could glimpse the implications of every action he took.

The author points out repeatedly that casting Holmes as a liberal saint is an oversimplification of a complex life. Certainly, he got a lot of things right by progressive standards. In these pages, you will find many examples of Holmes defending unions, free speech and other liberal causes—but, at the root of his reasoning, was always his belief that the law is not an eternally fixed set of immutable rules.

Budiansky appropriately devotes many passages to explaining this crucial balancing point in Holmes’ approach to the law. In simple terms: He repeatedly attacked “originalists.” He did not believe that judges should marching in lockstep based on orders inherited from long-dead jurists. The law must be hammered out and interpreted in each new generation, based on a just balance of Americans’ competing hopes and needs. If Holmes were alive today, he certainly would lash out at constitutional originalists with his caustic wit, and deep legal knowledge—but some of his decisions might surprise people.

That’s the greatest compliment I can pay to Budiansky’s new biography. Such a gigantic life cannot be distilled to a single sentence or a single image.

Holmes spent nearly a century on this planet. Because his father was one of the most famous writers of the 19th century—and hobnobbed with the likes of Emerson and Longfellow—Holmes Jr. grew up in a rarefied world of America’s leading lights. The roots of his values sprang from childhood interactions with writers and thinkers who were forming the American culture of roughly two centuries ago. Then, Holmes carried those ideas through the crucible of the Civil War and they evolved further through the tragic injustices uncovered in the Progressive Era of sweat shops and dire poverty for millions.

Many forces converged in this remarkable life—from early America’s greatest thinkers who surrounded him in childhood through the world leaders who dominated the early 20th Century. This is a slice of our shared history that most Americans have forgotten. Now, through these pages, we can watch this Great Soul emerge from battlefields, horrific injustices and raging intellectual arguments to defend the rights of men and women.

It is truly an inspirational journey.

I can’t wait to read this. Catherine Drinker Bowen’s bio “Yankee From Olympus” started me, at 17, on my intellectual and spiritual jaunt through American history, getting to the man Holmes wrestled to the ground in front of enemy fire–Abraham Lincoln, (“Get down you fool!” said the 6 foot 2 inch OWH,Jr.), the man who confronted William James at the Harvard Philosophy Club saying, “To think in no less than to feel!” The man who said, “Life is action and passion” and we must participate in the action and passion of our time at peril of not having lived.

OK? Have I gone over board?! Do scholars still credit all that?