After a traumatic death, you can help by ‘making room’

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

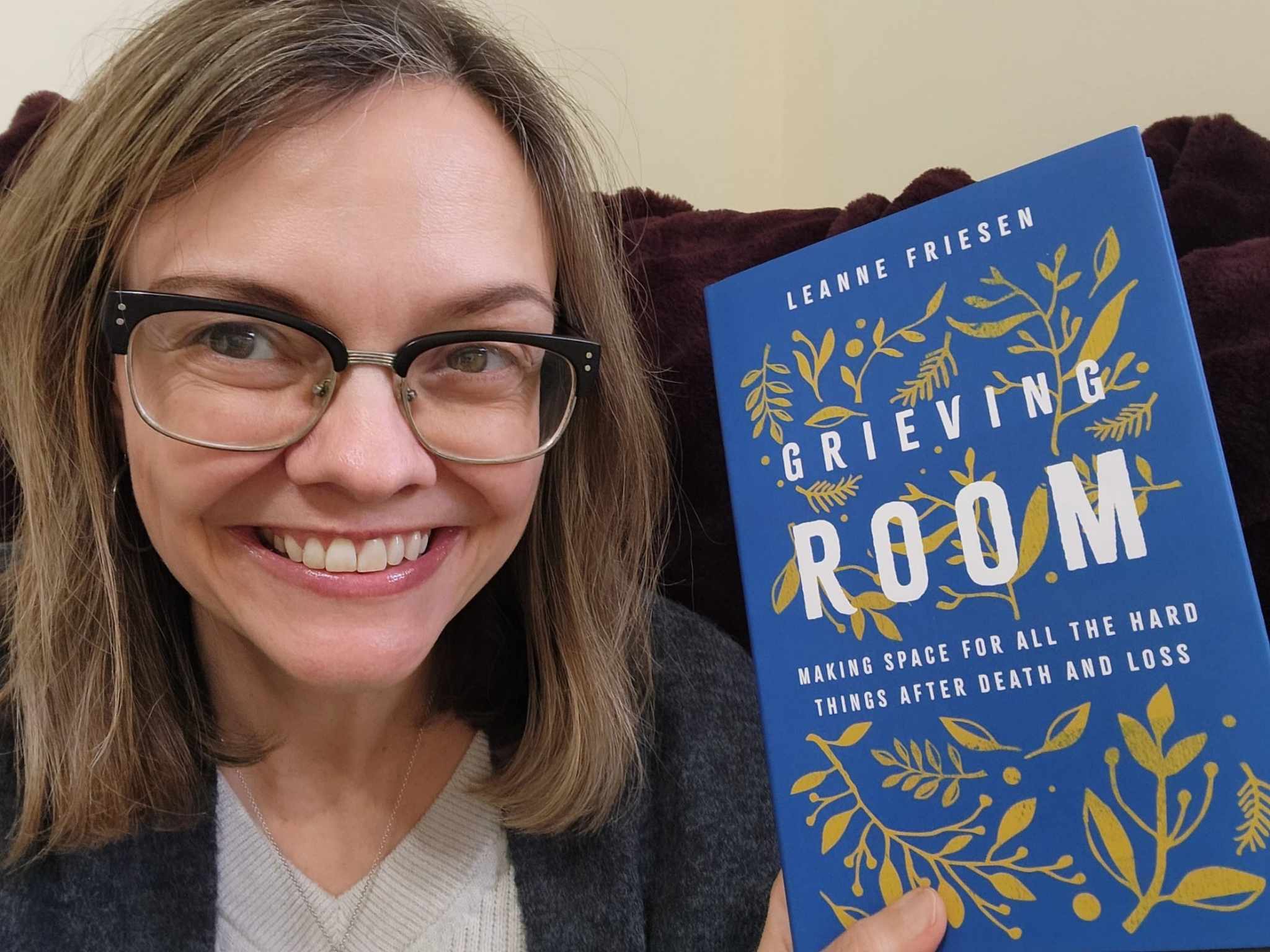

Halfway through Leanne Friesen’s new book, Grieving Room, my reaction was: This is both a daring and a rare book.

By that I mean: It’s a startlingly honest letter sent out into the world, especially pitched for readers in their 20s, 30s and 40s who need particular kinds of help with the long and twisting journey of grief.

Why is age an issue? Looking over the hundreds of books on the lingering effects of loss—grief can seem downright geriatric. When he published A Grief Observed, arguably the world’s most famous grief memoir, C.S. Lewis was 63. Only two years later, he followed his wife in death.

But, the truth is: Every year, long-term grief strikes millions of younger men and women—including Leanne Friesen in her 30s. At that too-young age, Leanne experienced the death of her too-young sister Roxanne. When Roxanne died of melanoma, Leanne already was an experienced pastor and thought she should be an expert in grief, which she wasn’t—yet. Eventually, in her 40s, and after living with her grief over losing Roxanne for a number of years, Leanne wrote this book to share their story with the rest of us.

And that’s the greatest value of this eloquent book: Leanne still is a relatively young pastor writing about grief among relatively young adults. At that age, our responses and relationships after a loved one’s untimely death unfold in different patterns, at a different pace and with different pressures than friends in their 60s, 70s or older experience after a death.

When I first read Leanne’s book, I was so moved by her insights that I posted an early review in Goodreads, explaining that her book was a solace for me as I continue to feel the loss of my own brother, many years ago, when he was only 39. Even though I’m now in my 60s, I could feel the authenticity of Leanne’s story of struggling to reclaim hope in her own life again after such an early loss. And, as I live with my own grief for my brother and others I’ve lost—part of my vocation is to publish columns like this one about the need to help each other with these journeys. Just last month, our magazine published a column by Jeffrey Munroe, author of Telling Stories in the Dark, about a man in his 90s who surprised Jeff by telling him about his heartfelt grief over the death of a brother many, many decades earlier. As I read Jeff’s column, I could feel that old man’s heartache. I can say quite honestly that I will be thinking of my own brother even into my 90s, should I live so long.

And that’s the most compelling reason to read Leanne’s book, I think. If you are grieving, this book assures us that this is a part of life we simply must accept and make room to explore.

The ‘bedeviling problem of age’ and untimely death

So, this potentially bedeviling problem of age was the first thing Leanne and I talked about in our interview about her book. The question that so many of us have wrestled with for years is: Does grief haunt us forever or are there ways to turn our paths, as we carry these memories, toward the hope of finding hope someday. Her book argues that there can be such a transformation—and I agree.

I said to Leanne: “One reason I want to recommend your book is your age, your sister’s age when she died, and what I think is this book’s value for millions of younger adults who are on this incredibly difficult journey—at what feels like an untimely age. Do you think I’m right in saying that?”

“I agree,” Leanne said. “I do think what you’re saying lines up with all the younger people who have connected with me online through my website and my Instagram page.” (That Instagram page, @grieving.room, has 34,000 followers!)

“When I lost my sister Roxanne, I was 35, and I couldn’t think of anyone I knew who had lost a sibling at my age,” Leanne said. “Often, the first loss in a person’s family is a much older relative like a grandparent—and those can be very shocking losses for people, of course—but that’s a different grieving experience than losing a sibling at such a young age.

“When you hit grief prematurely, you do feel profoundly alone—so I appreciate your saying that this book addresses that for readers. If my story can help other younger adults, then I am honored to be part of that. That’s why I continue to post to the Instagram @grieving.room—I can see from the responses that I get online that we do need to help each other make room.”

Why is this book ‘daring’?

I describe this book as “daring,” because it’s rare to read such an honest memoir by a pastor still in active ministry—especially when Leanne warns us about all the dumb stuff some acquaintances tend to say and do after a death in the family. She describes this honestly so that we, in our own grieving processes, will know we’re not alone in feeling hurt or bewildered by such responses—and to warn us away from repeating such things to folks we love when they are grieving.

Finding what we think are “wise words” after a death is an almost universal temptation. Especially after a traumatic death in one’s family, we receive a waterfall of well-meaning wishes from folks reassuring us that we can “cope,” “survive” and “get over it.” Such wishes—often accompanied by biblical-sounding adages—can have the opposite effect. If you have grieved, you probably recall all the unhelpful lines you heard—if not, read Leanne’s book to discover them.

At times in this memoir, Leanne admits to boiling with rage at thoughtless comments. She uses the word “anger” 34 times and “angry” 47 times—then “rage” or “raging” pop up 29 times, not to mention a fair number of times Leanne admits to having been “mad” or wanting to “scream.”

But, please, don’t get me wrong! This is a truly loving book. Leanne’s Instagram @grieving.room and her personal presence in our hour-long Zoom interview made it clear to me that she’s an exceptionally loving and generous person.

“I’m impressed that you write so honestly,” I told Leanne. “How did you summon the courage?”

“I decided to write honestly about these things because so many people misunderstand grief. Myths about death and grief are so common,” Leanne said in response. “I can tell you that, when someone walks up to me to talk at a funeral home, I’m mentally rolling the dice on what I’m about to hear them say. Sometimes people know what to say, but—all too often, what comes out is something that isn’t helpful—and may even be hurtful.

“That was one of my hopes in writing this book: I want people to know they don’t have an obligation to go ‘say something helpful’ to a grieving person,” Leanne said. “People who are grieving at a funeral don’t need friends to come up and theologize to them. They’re in the midst of grief. You don’t have to try to teach them something. There are so many other ways you can be helpful to them—ways that I write about in the book. I tried to make this book as helpful as possible.”

For example, she said, “I want people to to realize how long grief lasts—for years, just like we’ve been saying in this interview. Anyone who wants to be supportive to a griever should assume that anyone who has lost someone in the last year or two is still thinking about that—most likely every day. They’re likely still walking around in a bubble of grief. That’s certainly the way I was walking around for a very long time after Roxanne’s death. But people forget that, after a loss, especially a too-young loss or a traumatic loss, your life doesn’t go back to how it was before that loss.”

So, what can we do?

Start by ‘making room’

If you read Leanne’s book, you will discover that this is one of the most important “take aways” from Leanne’s book: We should help each other to make space in our lives for all the changes and challenges that come in the years after a loss.

In fact, Leanne is so intentional and practical about providing assistance that she closes her book with a 40-page section called “Reflections, Practices, and Prayers.” It’s a step-by-step series of suggestions for either individual practice or for group discussion and action.

And all of this rests on the central metaphor of “room”—the space grieving people need for a very long time after a traumatic death to adjust to the new world they are experiencing. “Room” is such a powerful metaphor that Leanne’s Instagram “room” is drawing new followers every day. When we met for this Zoom interview a few weeks ago, she was talking about the 31,000 people who had connected with her in that Instagram room—and this week, the total is already 34,000.

So, what is this “room” everyone’s buzzing about?

Well, that’s why you should order a copy of Leanne’s book in which all 20 chapter titles start with the word “room.” Between these covers, you’ll find a book-length amount of ideas to consider. But here’s just one example:

She makes a point in her book of recommending A Hole in the World, a recently published reflection on grief by Amanda Held Opelt, the sister of best-selling author Rachel Held Evans, who died at age 37. Leanne appreciates the way that book emphasizes the need to help younger people who are grieving “to make room for the rituals of death” in the midst of their own busy lives with the pressures of daily work and perhaps caring for children.

Then, in our interview, Leanne touched on one of her own favorite examples of “making room”: “I will never forget the two friends who understood what I was going through and made room for me in a practical way when Roxanne died. They had lost their father when they were in their 20s,” Leanne said. “They understood grief at an early age.”

In the book, she writes that these two friends responded to Leanne’s loss by volunteering to provide childcare to allow Leanne the uninterrupted “room we needed to remember Roxanne.” Leanne writes:

My children at the time were just 2 and 5 years old. … We didn’t have access to babysitters we knew who wouldn’t also need to attend the service, so I had wondered what we would do A few days before, I got a call from my friends, Jan and Jill, twins I had known since I was born. They explained to me that they had each taken the day off work so they could babysit my children during the funeral. I will never, ever forget this kindness. They were making room for our rituals, and in so doing, they made room for my grief. I felt swallowed up in compassion. I felt the blessing as we mourned.

‘Making room for hope’

After her years of navigating grief, Leanne has a great instinct for how she can now bless others by making room for them. She is a pastor, a scholar and now serves as a regional leader in her Canadian denomination. She also has become a popular retreat speaker and guest on many podcasts and online platforms. She earned her MDiv from McMaster University, plus a post-graduate certificate in death and bereavement from Wilfred Laurier University.

Her writing bears the marks of a thoughtful, natural storyteller who chooses each word for a precise effect. On the final page of her last chapter, Leanne writes that she hopes her readers will, someday, be able to make “room for the hope that you will not just get through your grief but that there can be ways that you will become a version of yourself that you will be glad to be.”

I love that phrasing because I so clearly recognize a fellow passenger through grief in that wording. Did you catch her nuance? She’s not promising readers that they will, indeed, “get through” their grief. She’s hoping that they will someday make room for hope. That sentence alone proves the illustrates of the wisdom of this book.

Care to learn more?

Want to connect with Leanne? Visit her at her website, LeanneFriesen.com, and visit her ever-growing Instagram community of friends @grieving.room

If you care to read a kindred book about rediscovering resilience after grief and other traumas, get a copy of Jeffrey Munroe’s new Telling Stories in the Dark. Both Leanne’s and Jeff’s books feel contemporary, honest and forward looking. These wise authors—both well acquainted with grief—are simply sitting down with us and sharing their hard-earned wisdom. They’re telling their stories, which millions of us need to hear—because they also are our own.

I closed my Goodreads review of Leanne’s book this way:

My hope is that many readers will find hope between these covers. And may Leanne Friesen continue writing for many decades until her life is so bursting with wonderment that we get the sequel to this wise and welcoming volume. And, God willing, may I be around to write another 5-star review.