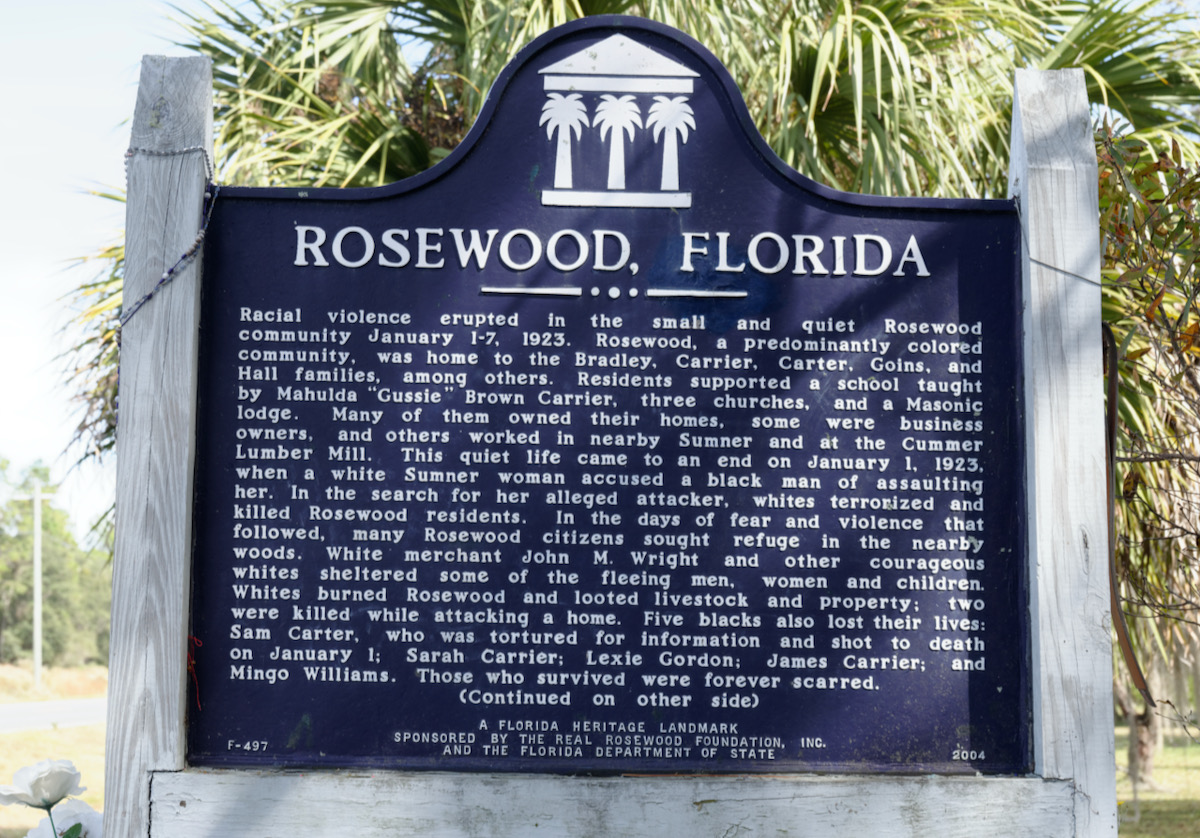

CLICKING ON THIS PHOTO will enlarge it for easier reading. The back side of the historical marker appears at the end of this story. (Note: This photo is in public domain, so you can feel free to share it with others.)

In 2023, let’s launch a new era of care for people in need.

.

By HENRY BRINTON

Author of Windows of the Heavens

One hundred years ago this week, the Rosewood Massacre began. Although unknown to many, Rosewood reminds us of the devastating impact of violence, especially on the most vulnerable members of our communities.

Rosewood was a quiet and mostly African American town in Florida. According to the History website, it was originally settled by both black and white people, and the main industry was the production of pencils. But when the cedar tree population declined, most of the white people moved to the nearby town of Sumner. By the 1920s, Rosewood’s population was about two hundred blacks, plus one white family that ran the general store.

On January 1, 1923, a young white woman in Sumner, Fannie Taylor, was found covered in bruises. She claimed that a black man had assaulted her. Her husband, a foreman at a local mill, gathered a mob of white citizens to hunt down the assailant. He also called for help from neighboring counties, including five hundred members of the Ku Klux Klan. The white mobs searched the woods for any black man they could find.

Law enforcement determined that a black prisoner named Jesse Hunter had escaped from a chain gang. They immediately made him a suspect. The mobs focused their searches on Hunter, and went after black families that they believed were hiding him.

Death and destruction in Rosewood

In Rosewood, one mob pulled a black man out of his house, tied him to a car, dragged him to Sumner, and beat him. Another mob tortured a blacksmith until he took them to the spot where Hunter was said to be hiding. When Hunter was not found, they shot the blacksmith and hung him in a tree.

In Rosewood, one mob pulled a black man out of his house, tied him to a car, dragged him to Sumner, and beat him. Another mob tortured a blacksmith until he took them to the spot where Hunter was said to be hiding. When Hunter was not found, they shot the blacksmith and hung him in a tree.

On the night of January 4, a mob of armed white men surrounded a house in which twenty-five people were hiding, mostly children. Shots were fired, and a black woman and her son were killed. Two white attackers were also killed.

The gun battle lasted overnight and ended when the whites broke down the door and the black children escaped into the woods.

Newspapers falsely reported that bands of armed black citizens were going on a rampage. White attackers burned down the churches of Rosewood, and then went after people in houses. Dozens died, both blacks and whites. By January 7, most of the town was burned to the ground, and the fleeing black citizens never returned.

As for Fannie Taylor, the young white woman? Some survivors believe that her bruises were inflicted by a white lover. And Jesse Hunter, the escapee from the chain gang? He was never found.

Violence in Our Scriptures

Jews, Christians and Muslims are familiar with the threats faced by Moses and Jesus at the very beginning of their lives. In ancient Egypt, Pharaoh feared the growing power of the Israelites, so he gave the command, “Every boy that is born to the Hebrews you shall throw into the Nile” (Exodus 2:22). But the daughter of Pharaoh rescued

Moses and took him as her son.

Years later, Jesus faced deadly violence at the beginning of his life. After the wise men left Bethlehem, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,” he said, “take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt …. for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him” (Matthew 2:13).

King Herod was feeling threatened by the birth of this baby who had been identified as the king of the Jews. He didn’t want any competition, even from a child who had no political or military power at his disposal. Feeling frightened and infuriated, Herod ordered a search and destroy mission to be carried out in Bethlehem.

In both the ancient world and today, we know the devastating impact of violence, especially on vulnerable children and adults.

Resentments can lead to violence

Unfortunately, the feelings that drove Pharaoh and Herod to violence are still alive and well. According to The Guardian, Rosewood was a prosperous black town in 1923, “with its own baseball team, a masonic temple and a few hundred residents.” A black survivor of the massacre says that whites were disturbed because they looked at Rosewood and saw a bunch of black folks “living better” than white folks.

Such resentment can lead to violence, both then and now. When we remember Rosewood, we see that the bloody story remains the same.Looking around today, we see resentments that can lead to violence. Many residents of Blue States resent residents of Red States, and vice versa. Many native-born citizens feel threatened by immigrants, and immigrants feel anxious in the United States. Fault lines appear between members of different racial and cultural groups, between gays and straights, between the old and the young.

We look at the world and feel threatened, which is exactly what Pharaoh and Herod experienced. But what if we looked at the world and saw the presence of God? Neighbors are gifts, not threats As people of faith, we are challenged to see our neighbors as gifts, not threats.

“When you meet another person,” says author and pastor John Pavlovitz, “you are coming face-to-face with a once-in-history, never-to-be-repeated reflection of the image of God. … each [is] made of God stuff …. Every single day you encounter thousands of breathing, animated thumbnails of the Divine.”

Every person you meet is God stuff. Whether native-born, immigrant, gay, straight, old, young, Red, or Blue, your neighbors are “thumbnails of the Divine.” They are gifts, not threats. Worthy of respect, not hostility. What a difference this makes, when we remember Rosewood.

Protecting the vulnerable

Once we see our neighbors in this way, we are challenged to take action to protect the most vulnerable people around us. They could be special-needs adults, low-income neighbors, recent immigrants, political refugees, members of a minority group, or neighborhood children.

After Jesus was born, Joseph and his family lived as immigrants in Egypt until an angel appeared to him and said that it was safe to return to Israel. Then he returned, but made a detour when he learned that the son of Herod was ruling over Judea. Instead of moving to Bethlehem of Judea, he headed north to Galilee, and moved into the town of Nazareth.

This story contains so many examples of vulnerability: Jesus and his family were political refugees, immigrants, members of a minority group in Egypt, and finally Southerners who settled in the North. And just as Joseph cared for his vulnerable child and wife, we are challenged to care for the at-risk people around us.

Daring to be heroic

Sarah Carrier (left), Sylvester Carrier (standing) and his sister Willie Carrier (right) in a family photo taken around 1910.

Among the heroes of Rosewood were brave at-risk Black women and men, including Sylvester Carrier. But some of the heroes of Rosewood were white. John Wright, the white owner of the general store allowed families in peril to hide in his home during the massacre. Two wealthy white brothers, John and William Bryce, heard about the violence and sent a train to rescue women and children.

A survivor of the massacre, who was a young girl at the time, recalled Sylvester’s courage. “Cousin Sylvester snatched me and said, ‘Come here, let me save you. …’ I squeaked down between his legs.”

When we hear “wailing and loud lamentation” (Matthew 2:18), our challenge is to respond with compassion and care. We cannot cover our eyes and our ears, ignoring the violence being done around us. When Jesus grew up and saw vulnerable people around him, he “had compassion for them” (Matthew 14:14).

The word compassion comes from the Latin words passio and com, which literally mean “suffer” and “with.” To have compassion is to “suffer with” people, to take their pain seriously and do whatever we can to alleviate it.

When we remember Rosewood, we are challenged to identify with the victims of racism and discrimination and violence, and take action to protect the innocent and vulnerable people around us.

Pharaoh’s daughter did this when she took pity on Moses.

Joseph did this when he took Jesus and Mary to Egypt.

John Wright did this when he took his at-risk neighbors into his home.

Sylvester Carrier did this when he defended his home and saved the children in his care.

This week is not a happy anniversary. But it can be the first week in a new era of care for people in need.

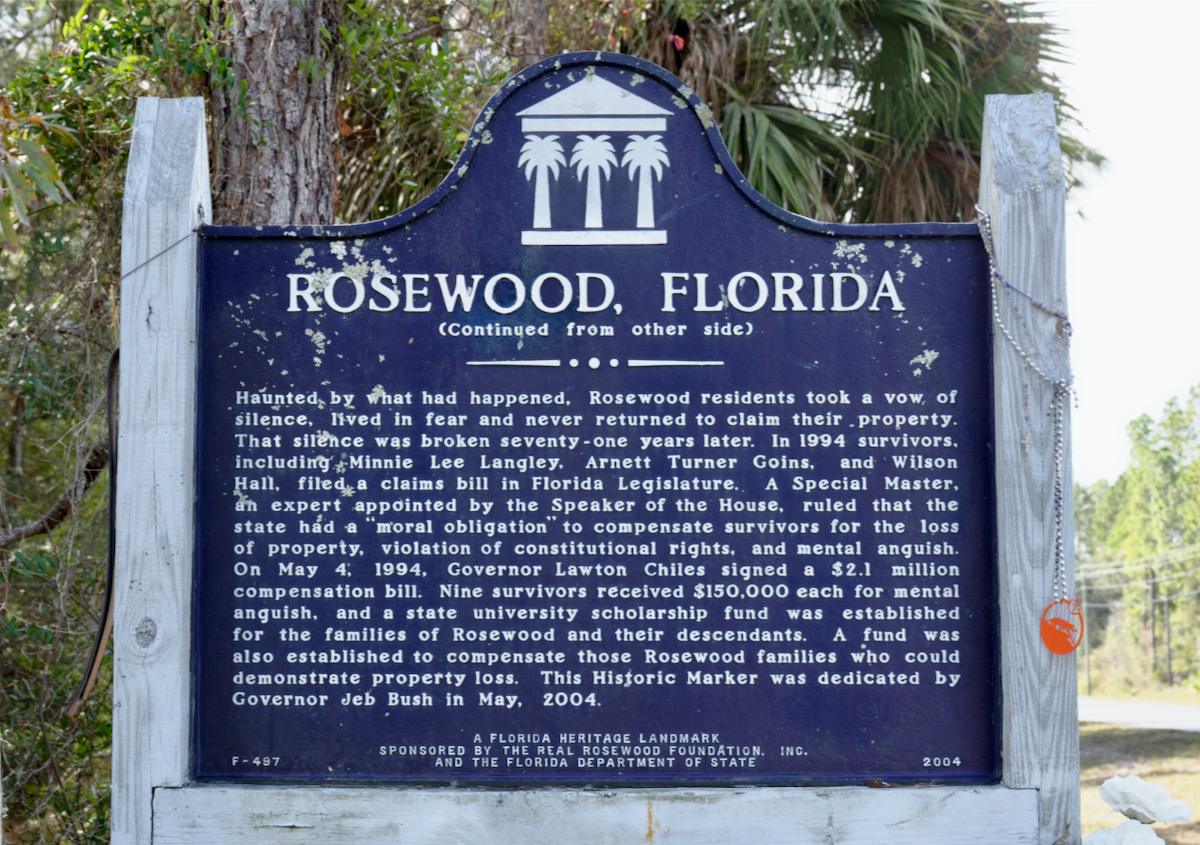

CLICKING ON THIS PHOTO will enlarge it for easier reading. (Note: This photo is in public domain, so you can feel free to share it with others.)

Care to learn more?

Henry G. Brinton is an author and a Presbyterian pastor who has written on religion and culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today and Huffington Post. A frequent speaker at workshops and conferences, he is the author of books ranging from Windows of the Heavens to The Welcoming Congregation: Roots and Fruits of Christian Hospitality. Henry and his wife, Nancy Freeborne-Brinton, have two children, Sarah and Sam. An endurance athlete, Henry has completed a marathon, triathlon, or century bike ride a year since the year 2000.

Henry G. Brinton is an author and a Presbyterian pastor who has written on religion and culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today and Huffington Post. A frequent speaker at workshops and conferences, he is the author of books ranging from Windows of the Heavens to The Welcoming Congregation: Roots and Fruits of Christian Hospitality. Henry and his wife, Nancy Freeborne-Brinton, have two children, Sarah and Sam. An endurance athlete, Henry has completed a marathon, triathlon, or century bike ride a year since the year 2000.

.

.