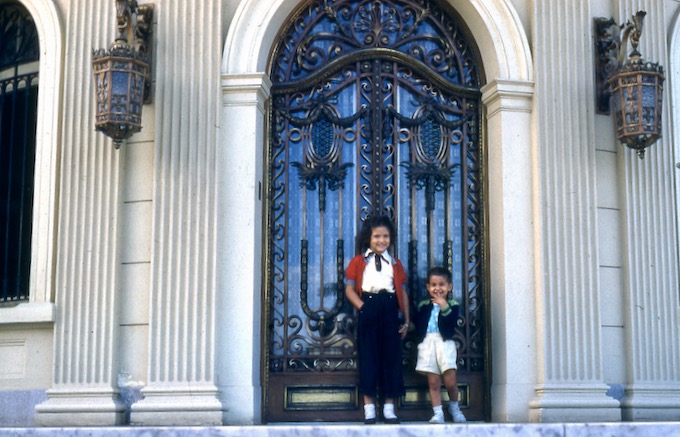

BEFORE THEY HAD TO FLEE CUBA, Loly (Delores) and Gerry Mauriz pose happily in front of their family home in Havana, which later was seized by the government and now is a hotel.

We’re blessed with good friends at Laurel Oak CC in Sarasota, FL. Among them, Yolie and Gerry Mauriz, both of Cuban descent. Their stories are a reminder of how one man can change history. And peoples’ lives.

Fidel Castro took over Cuba in 1959. “We were used to changes in government,” Yolie says. “Initially Castro was considered just another phase that would pass.”

Gerry’s Story

Gerry, then 9, and his family lived in the Havana 5th Avenue mansion, Villa Eulalia. The home belonged to his grandfather, Gabriel Palmer Bestard, who owned shipyards, ships, a fishing fleet and dredging barges. Bestard arrived, alone, in Cuba in 1904 at 15, from Spain. He went through many trials before starting his business. He ultimately employed thousands. As a result, Bestard’s businesses and bank accounts were among the first to be confiscated. (You’ll find more of his dramatic story at the end of this column.)

Gerry remembers being “terrified by Castro’s people,” especially when a bomb blew up in a neighbor’s garbage can.

In 1960, Gerry, his parents, grandmother and sister left for Miami as tourists. They were accepted in the US with indefinite voluntary departure status. “We arrived broke,” he says. “Even so, we were ecstatic to feel free and unafraid.”

Gerry’s dad had contacts with NY-based shipping magnate Malcolm McLean, who originated container ships. McLean put Gerry’s father in charge of his refrigerated cargo division in NJ. Most of Gerry’s father’s family stayed behind in Cuba, thinking they could “correct what was clearly a mistake.” 6 months later, many of Gerry’s uncles and aunts arrived in Miami.

Gerry explains Castro’s rise this way: He first destroyed Batista’s army, executing officers after mock trials. He then attacked the wealthy, promoting socialist/communist ideals, accusing the wealthy of graft and corruption. Next he demanded allegiance from the masses.

Gerry says, “In a few short years, the government took over all businesses, down to gas stations and bakeries, and destroyed any means of opposition.” Gerry’s anti-Castro uncle, Atanasio (Cuco) Palmer, was imprisoned and tortured at the infamous La Cabaña, which housed a dank centuries-old Spanish dungeon run by Che Guevara. Daily, Cuco was taken outside and stood by a wall before a firing squad. Though the bullets shot at him were blanks, the experience so affected his health he died soon after. (Today, La Cabana is a tourist attraction with live bands and a full bar at the very wall where Cuco stood. Villa Eulalia is now a swank hotel.)

THE DAY BEFORE YOLIE’s FAMILY LEFT THE COUNTRY,, they posed for a final photo in Cuba on August 4, 1962. Yolie’s cousin Silvia and her parents are on the left; Yolie and her parents are on the right. The boy in front of Yolie is her little brother Emet, who arrived in the U.S. later with Yolie’s parents aboard a Red Cross ship.

Yolie’s Story

Yolie, 8, lived in Varadero Beach, about 2 hours east of Havana. Her dad, Emeterio, had a successful architectural practice and occasionally worked for the county. Yolie attended a private Presbyterian school, La Progressiva, where her mother and great aunt had both taught. Her school was taken over by the government and pro-Castro teachers brought in. Yolie soon realized when her teacher called on her, whatever she said was “wrong unless it was an ‘approved’ answer.” Yolie’s parents took her out of school; she was tutored by her aunt. Her mom was threatened with revoking Yolie’s food ration card unless Yolie returned to school.

Castro began separating children from parents and sending them to “educational” camps in the country. Yolie’s family, especially her father who’d attended university with Castro, understood the danger of staying in Cuba .

After the Bay of Pigs fiasco in April, 1961, “everything changed,” Yolie says. A CIA-trained force of 2500 Cuban exiles, the 2506 Brigade, invaded Cuba from the south at Bay of Pigs. A CIA-sponsored anti-Castro faction within Cuba was ready to fight, backed by promises from JFK of military support once the beachhead was established. The invaders planned 3 airstrikes using B26 WWII bombers. The first attack destroyed 1/3 of Castro’s air force. JFK stopped the next 2 planned airstrikes. As American warships sat just outside Cuban waters, the anti-Castro forces ran out of supplies. Without promised US support, Yolie says, “the invasion was doomed.”

Yolie remembers opening the door for soldiers who searched her house seeking 2 of her uncles. They found them elsewhere and threw them into a Spanish dungeon in Matanzas. Like Gerry’s uncle, her dad’s brother was taken out repeatedly, stood against a wall, and shot at with what turned out to be blanks.

In July, 1962, Yolie’s parents learned their daughter and her cousin Silvia could obtain visas to leave. Her cousin’s father remained in jail. Yolie, 9½, and Silvia were sent to the US on what became known as the Peter Pan Migration of 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban minors. The concept was begun by a Catholic priest in the US; other American churches joined in. 2 months later, after the Cuban Missile crisis, the Castro regime shut down the program.

Yolie lived briefly with relatives in Miami, then went to the home of her mother’s sister, Bertica, in Chicago. She knew some English from reading Dick & Jane books. Silvia went to a way house organized by Cuban exiles in Miami and to 2 foster families before being claimed by Yolie’s family. “We didn’t know if we’d ever see our parents again,” Yolie says.

In March, ’63, the US sent 2 Red Cross ships to Havana with medical supplies—ransom, Yolie says, for freeing captured invaders. To obtain housing for Russian immigrants, Castro returned the ships filled with refugees, including Yolie’s mom and dad and Yolie’s brother Emet. “Fortunately,” Yolie says, “there was little time to check credentials. As a ‘professional,’ my dad wouldn’t have been allowed to leave.”

Yolie’s family arrived in Miami “with just the clothes on their backs, empty suitcases and no money.” Again relying on faith-based contacts, Yolie’s father was hired by the National Board of Missions for the Presbyterian Church in NYC. He designed churches for the rest of his life. The First Presbyterian Church of Springfield, NJ, adopted the family and provided them with essentials, including housing. Her grateful mom became a full-time volunteer for the church.

Yolie and Gerry Meet

As the only Cuban families in Springfield, Yolie and Gerry’s parents met. Yolie and Gerry met later, as teens. Yolie became a microbiologist; Gerry, a worldwide surety director for a large insurance company. The high school sweethearts married in ’75 and have 2 adult sons.

Yolie’s become a birder, having spotted and identified 400+ species. Both enjoy golf and photography.

Their attitude toward immigration? Gerry says, “Billions of people around the world want to come to the US. We’re a nation of immigrants. We should continue welcoming immigrants, but there have to be reasonable rules and procedures. When we arrived, we didn’t ask for free medical care or food. My dad did whatever it took to take care of us. All we wanted was opportunity.”

Would they return to Cuba?

No.

Yolie says, “It doesn’t take much to change the course of a nation. Castro promised equality, but except for the elite in the armed forces and government, Cubans got equal misery. He promised freedom but gave us oppression and subservience.”

Gerry says, “We don’t want to provide tourist dollars to the Cuban government—an important source of revenue.”

Americans should learn from the Cuban story, Gerry says. “Know and understand your rights. Protect them. Don’t be swayed by rosy promises. If something sounds too good to be true, it usually is. No one but you will protect your family.”

Thanks, Yolie and Gerry, for reminding us how lucky we are. As imperfect as this nation may be, I stand, cover my heart and tear up whenever I hear “The Star Spangled Banner.” I can’t say it often enough: God bless America.

WHEN THEIR HAVANA SHIPYARDS WERE IN THEIR PRIME, Gerry’s grandfather stands at left and his brother Bartolo is at right.

Gerry’s Grandfather’s Story

Gerry’s “rags to riches” story of Gabriel Palmer Bestard, his grandfather, was so fascinating I’m including it…

Gabriel Palmer Bestard arrived in Cuba from Estellencs, Majorca, Spain, at age 15 in 1904. In Spain he finished 5th grade and was then trained to build ships as a “Carpintero de Rivera.” In Cuba, he did many jobs to survive, including one which required wading in waist deep dirty water for 16-17 hours a day. He was hospitalized for a leg infection. When the doctor planned to amputate, Gabriel waited until night and escaped out a window.

After he married, Gabriel worked odd jobs during the day. At night he built boats on the roof of the building where he lived. The landlord threw him out.

He met a wealthy man who saw Gabriel’s potential and helped him go into business. Around 1919, he was able to buy the land along Havana Harbor. The shipyard he started grew to be the largest in Cuba. Over the years, he expanded into dredging, a fishing fleet, tugboats, real estate and a small distillery.

In the 1930s, a hurricane threw a large ship ashore in Cardenas. US and French salvage companies declared the ship beyond saving. Gabriel approached the insurance company with a price, offering to fix the ship. If he failed, he said, the insurance company wouldn’t pay him anything. Using his dredges and tugboats, he dug a channel to the ship. At high tide when the channel filled, he pulled the ship out. “A huge financial success,” Gerry says. In the early 1930s, the Cuban government refused to pay its external debt. Gabriel bought large amounts of Cuban bonds for pennies on the dollar. When the government eventually paid the debt, he made another fortune.

Gabriel returned to his small hometown in Spain every 2 or 3 years. Each time he implemented some major project, including putting in a power plant and electrifying the town in the early 1930s. “He was his town’s guardian angel,” Gerry says. “He solved many problems. To this day his name is revered in Estellencs.”

In Cuba, Gerry says, Gabriel took care of his workers, paying their medical bills when they were sick. His wife Eulalia spent thousands of dollars sending toys and food to less fortunate families. “My grandfather taught me to respect all people, no matter how humble their condition.”