This is part of a series of books that have been influential in my life, going back to grade and high school and on to the present. It would be nice if these posts started a dialogue–what books influenced you, the reader, and why or how?

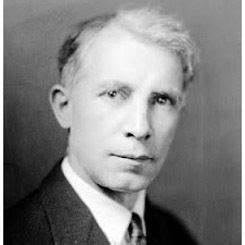

I was a senior in high school when someone told me about Richard Gregg’s remarkable book. A graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School, the author had worked in labor relations with corporations and then with unions. He writes how his life was turned around during a strike in the 1920s:

“In the middle of that big strike when feeling was most bitter, I happened to see in a Chicago book shop an article about Gandhi which gave some quotations from him. They impressed me so much that I got hold of everything about him and by him that I could find. After considerable thought I decided to go to India to find out about Gandhi and his methods at first hand, for he seemed more like Christ than anyone I had heard of in the present world. I took some short courses in agriculture at the University of Wisconsin, worked a season on a Wisconsin farm, end set sail for India on January I. 1925.”

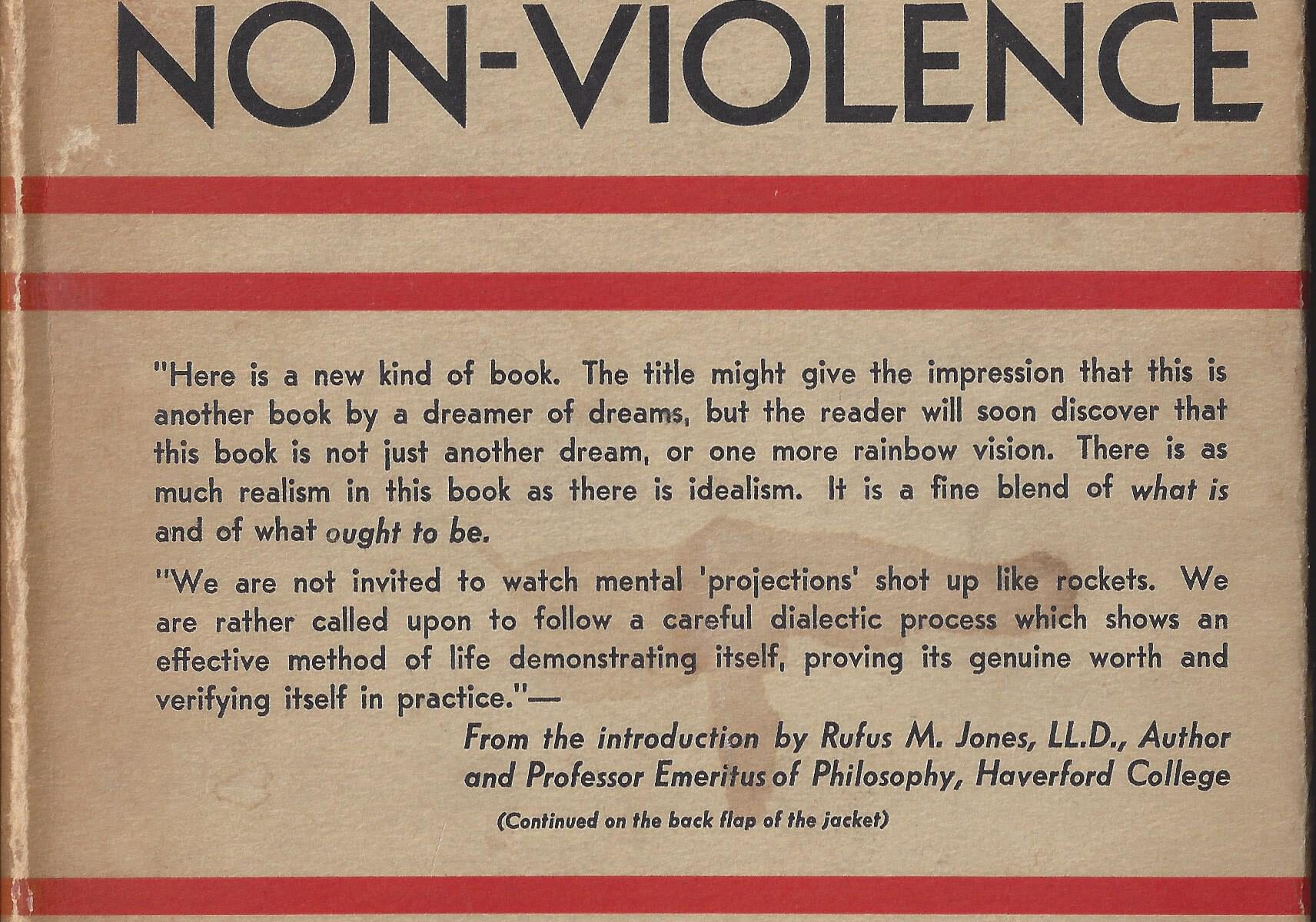

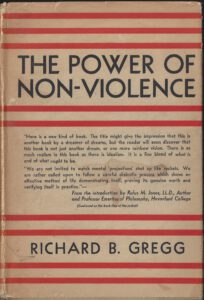

During his almost 4 years in India Gregg spent close to 7 months living in Gandhi’s ashram, becoming acquainted with the Mahatma and his associates and their nonviolent revolution against British rule. During this period he also corresponded with W.E.B. Du Bois, and during his second trip to India in 1930 to observe Gandhi’s Salt March to the Sea, he sent Du Bois two books he had written. Returning to the USA in 1928, he began working on his groundbreaking book, one that was to influence Rufus Jones, Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King, Jr. and countless others. His book was different from the many others dealing with pacifism in that it goes beyond the moral and theoretical to include history and psychology.

His first chapter “Modern Examples of Non-violent Resistance” recounts several examples of the power of nonviolence in Hungary, South Africa, and India. The rest of the book is his examination the hows and whys of nonviolence, or satyagraha as his friend and mentor Gandhi called it, this derived from the Indian words for “soul force.” He points out that in most conflicts there is a basic agreement between the opponents, namely that violence is the appropriate, indeed the only, way to settle their dispute. But, when one person refuses to retaliate physically, that agreement is broken, and the attacker is surprised, thrown off balance by the opponent’s unexpected response. Gregg calls this in his analytical 2nd chapter “Moral Jiu-Jitsu.” Thrown off balance and confronted by an opponent who steadfastly communicates good will, not hostility, the attacker is often confused, and sometimes reconsiders his view of the enemy and the dispute. This seldom leads to instant reconciliation, but with time, persistence, and discipline, it can be transforming.

The nonviolent resister does not always “win,” but Gregg points out neither does the espouser of violence. Indeed, violence usually leads to more violence, as world history shows us so sadly. By breaking the cycle of violence, the nonviolent resister leaves open the door to understanding and reconciliation. As Gregg points out, the British occupiers were worn down and departed India on friendly terms with the Indians rather than as defeated hostiles. In the book’s 26 chapters Gregg goes into considerable detail about mass nonviolent resistance, organizing for resistance, and the discipline required to adhere to one’s principles.

I had drifted away from the church, and the book convinced me that Christ’s Sermon on the Mount was not just idealistic fantasy but a transforming power. Through the years I have returned to the book many times to see how well Gregg explains such Biblical passages as Proverbs 25:21-23 ( If your enemies are hungry, give them bread to eat, and if they are thirsty, give them water to drink, for you will heap coals of fire on their heads, and the Lord will reward you) and Romans 12:19-21.

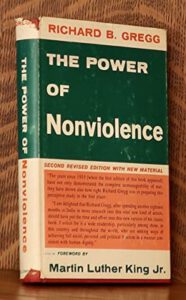

He revised the book for a 2nd edition in 1944, and then a 3rd in 1959, with Martin Luther King, Jr. writing a Forward. Glen Smiley of the Fellowship of Reconciliation had given Dr. King a copy of Gregg’s book. After reading it, King wrote to the author: ““I don’t know when I have read anything that has given the idea of non-violence a more realistic and depthful interpretation. I assure you that it will be a lasting influence in my life” That it was! Gregg/Gandhi’s ideas were influential in both the Montgomery Bus Boycott and in the writing of Dr. King’s Stride Toward Freedom. Dr. King listed Gregg’s as one of the 5 most “influential books” that he had read.*

For Gregg, as well as Gandhi and Dr. King, nonviolence was not just a tactic to be used in a dispute when an enemy was stronger, but a way of life. He saw nonviolence as part of his spiritual view of the universe, and thus believed that what connected us with our enemy was stronger than anything that divided us.

I paid $ .35 for my first copy of the book, the original 1934 edition, and have found it worth a million times that in my life. I eagerly bought the 1959 edition because of Dr. King’s Forward to the book and Gregg’s additional material on the resistance to the Nazis in Norway. I have sold off several thousand of my books through the years as I continue to downsize, but never these two treasures ‘

* I will be reporting on one of the other 5 next time, for following hard upon my acquisition of Richard Gregg’s book, it too was a big influence upon my life.