Movie Info

Movie Info

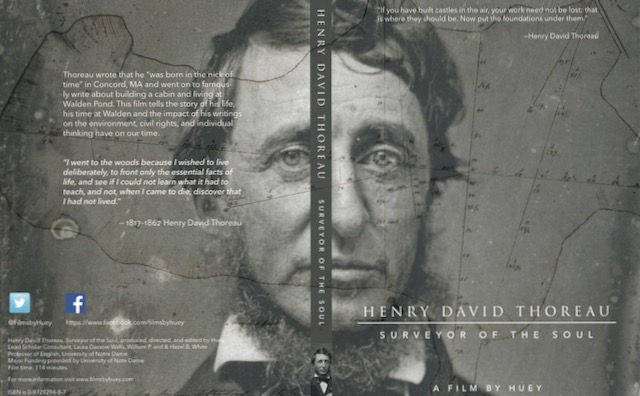

- Director

- Huey

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 53 minutes

- Rating

- Not Rated

On DVD

Not Rated. Running time: 1 hour 53 min.

Documentary, no violence, vulgar language, or sex.

Our stars (1-5): 5

You shall not follow a majority in wrongdoing…

Exodus 23:2a

Mention Thoreau, and everybody knows you are speaking of Henry David Thoreau, poet, philosopher of Nature and essayist of civil disobedience. In Maine, mention Huey, and a great many people will know you are talking about the long-time educator and filmmaker who chooses to leave off his family name in the credits. Huey’s newest film gives us a thorough picture of Thoreau, aided by various scholars, teenage students and their leaders involved in projects inspired by him, archival pictures and visits to numerous sites associated with the philosopher, and a talented impersonator, referred to as an “interpreter,” plus, of course numerous doses of his perceptive writings.

Even if you are familiar with snatches of Thoreau’s “purple prose” emblazoned on so many posters through the years, this film has much to teach you about this amazing man who stuffed so much zest and wisdom into his far too short 44 years. I was intrigued to learn of his close connection to the ubiquitous pencil, that as a teenager while working for his father’s small firm that manufactured and sold pencils, he developed a machine that removed impurities from graphite, so that his family’s pencils were said to be the best in New England. I never knew that he had an older brother John who loved the same girl that Henry did, or that the two had for a few years joined together to set up a school. (Earlier Henry had quit as a school teacher when it was demanded that he use corporeal punishment rather than persuasion to maintain discipline.) John’s untimely death was a huge blow to the writer that ended the progressive school. Henry met revolutionist John Brown when the latter came seeking financial support from admirers, and later defended vigorously him in speeches just before the government executed him at Harper’s Ferry.

Of course, the film offers far more than just biographical information, the filmmaker’s major concern obviously being to show us the lasting and widespread influence that Thoreau’s ideas have had on the world. The filmmaker does this by various means, starting with quick, recurring shots of memorial stories of major figures indebted to him—Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Muir being the foremost. Then there are sequences involving young people at Walden Pond and at a camp in Vermont studying and discussing his ideas. The youth are at an ideal age to reflect upon his words. One quotation that we see time after time emblazoned on a sign at Walden is: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” His stress upon the importance of being in the present amidst the beauty of nature, and of living a life of simplicity are explored by the youth, as well as by the various scholars interviewed. The testimony of several Penobscot Indian guides concerning what Thoreau learned from their ancestors when he visited Maine is also of great interest.

Of course, there are many, many shots of Walden Pond where Thoreau built his cabin on land owned by the famous poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, who had become his mentor and, at various times, his host. Thoreau lived in the cabin for two years, writing about his experiences in a series of journals. The original cabin is gone, but it’s site is clearly marked by a memorial, and we do meet Richard Smith, the skillful Interpreter who looks and sounds like Thoreau as he responds to visitors in the essayist’s words. We also visit the Thoreau home in nearby Concord, which has been carefully restored and opened for tours.

My favorite section of the film deals with the “Essay on Civil Disobedience,” which I first read when I was in high school, but not in a class, where all that I can recall being told about him was that he was a poet and naturalist living beside a pond. I came to him backwards, from my interest in Gandhi and his campaigns of civil disobedience, learning that it was the American Thoreau whose Essay had a great influence on the Mahatma when he was in South Africa developing his nonviolent philosophy. One of the film’s many interviewees is historian Howard Zinn, who speaks about the Essay and the writer’s living up to his words by refusing to pay his poll tax. This lead to his arrest and incarceration in the town jail for a night. He was upset the next day when his aunt paid the tax for him, because he saw his act as a repudiation of the government’s support of slavery and of the Mexican War as an extension of that abomination. The filmmaker visually underscores the revolutionary nature of the Essay and his defiant act by frequent cuts to the Concord Bridge where the shots “heard round the world” were fired, as well as by a shot of The Declaration of Independence itself.

We learn of Thoreau’s visits to Maine, Staten Island, Cape Cod, as well as to Minnesota, some of which resulted in books filled with keen insights. Thoreau was working hard on his writings when in 1862 he succumbed to the tuberculosis which had plagued him off and on since his student days at Harvard. The film gives a quote from the eulogy that Emerson gave at his friend’s funeral. “No truer American existed than Emerson.” The film concludes with a series of short statements by the people whom we have met throughout the film, each displaying the lasting impact this 19th century American has had upon them in the 21st century.

Huey’s film provides a good companion to reading Thoreau’s works—indeed, I have been so inspired by the film that I’m starting to revisit the few works that I have read and launch into some less familiar ones. The film’s subtitle comes from one of the means by which he earned his living, that of a land surveyor. This portion of the film leads to an intriguing exploration of how he moved beyond boundaries, taking positions beyond the accepted ones. That he marched to “a different drummer” is seen by his delivering three different times his ardent defense of John Brown, this at a time when society condemned the insurrectionist as a dangerous traitor. Some of his friends and associates urged him not to champion the condemned man, but Thoreau was too much of an abolitionist to remain silent.

This is a DVD that should be in every library, personal or public. Thanks to its chapter headings making it easy to go directly to specific topics, it lends itself for use in classes and study groups. Maybe it will inspire and encourage a young person to take up the mantle of a prophet and speak to the sanctioned wrongs of our own times.

To purchase this highly usable film or find out where it might be screening, go to the “Films by Huey” site at http://www.filmsbyhuey.com/.

This review with a set of discussion questions is in the July issue of Visual Parables.