Movie Info

Movie Info

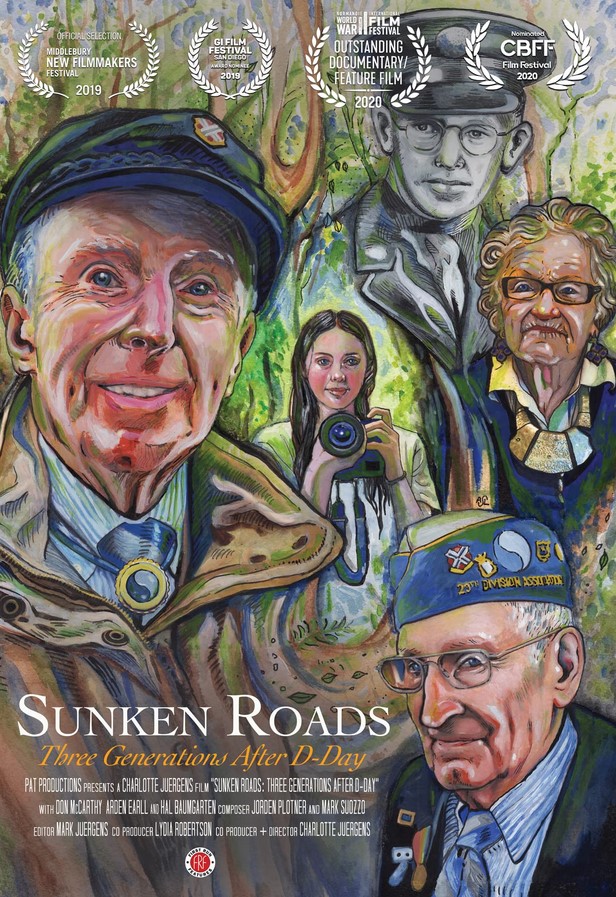

- Director

- Charlotte Juergens

- Run Time

- 1 hour and 31 minutes

- Rating

- Not Rated

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 2/10

- Language

- 0/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 0/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

Remember the days of old;

consider the years long past;

ask your father, and he will inform you,

your elders, and they will tell you.

Film director Charlotte Juergens was the same age as many of her interviewees were when they landed on the deadly shore of Normandy on that blustery June 6, 1944—20 years old. Traveling to Normandy with several of them in celebration of the 70th Anniversary of D-Day, she survived (indeed thrived)—many of their comrades did not. Well into the film we learn that the casualty rate for those in the first wave of boats that headed toward Omaha Beach was 85%! There were 10,000 Allied casualties on D-Day, with 4,414 of them dead.

Although we learn a lot about the D-Day invasion, this is not the film for those wanting “the big picture’ of the event that changed history. There are plenty of such historical documentaries—and of course lots of Hollywood epics, most notably Stephen Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan. Jurgens is interested not in the big names, the planners and commanders, but in the foot soldiers. Indeed, her interest is personal, as she wrote during a campaign to raise funds for her film:

“In June 2014, I traveled with a group of American veterans from the 29th Infantry Division, as they retraced their route from D-Day.

My great grandfather, also a D-Day vet, belonged to this same division, and this family connection fostered a unique closeness between the veterans and myself. These men have permanently shaped my life. They saw me as their granddaughter and shared stories with me unlike any I’ve ever heard…”

Juergens’ great grandfather Pat had died before she was born, but she felt fortunate in that her mother, also a filmmaker, had tape recorded an interview with him about his war-time experience, some of which is used at the beginning and end of the film, interspersed with Charlotte’s own narrative. She is able to go to France by agreeing to help chaperone a couple of members of an elderly group of veterans. She becomes especially close to Don McCarthy, a personable nonagenarian full of stories. Others of the men, such as Arden Earll are distant at first, but eventually come around as they spend time together retracing their youthful haunts. In England they visit the places they had lived and the moors where they had trained with live ammunition being fired over their heads. Then it’s on to France.

The men’s stories are memorable, and deeply personable. Hal Baumgarten tells how he had painted a large Star of David on the back of his helmet to honor his Jewish relatives. “It was my act of defiance (against the Nazis),” he says. Another describes the horror of being in one of the landing craft crowded with 29 grunts and an officer, the sides of the craft so low that waves would wash over them. Because of the obstacles the Germans had placed in the water, their craft could make it all the way to the beach. When the soldiers rushed forward they found themselves plunging into water a little over five feet deep—the short soldiers drowned because of their heavy gear, the tall ones survived—just barely, the water rising to his chin, the vet reports. He (or it might have been another) reports of seeing a good friend next to him in the water, but when he came up to him, discovered that he was dead. He carried the body to shore, using it as a shield against the heavy German fire that would have killed him. He solemnly says that It took him over 25 years to get over what he had done. In other boats virtually all of the men in the front rows were killed by the hail of German machine gun bullets.

Don has a story that we hear twice. After finally getting off the beach and heading for Saint Lô, he says a French girl appeared at a door and signaled to him to stay quiet. Two German soldiers passed just as Don hid. Later, after the vets visits the home of Suzanne Gandon, who has been Don’s friend for thirty years, he says that she is that girl, even though in the first telling he says that he has transferred that role to her. The jolly Suzette accepts the fiction at a festive gathering of the group. She also shares the real story of her and her mother hiding in a trench where they could hear the sound of German tanks approaching them.

There are numerous ceremonies before, during, and after June 6, with the French openly displaying their gratitude to their liberators. The bagpipes, bands, choirs, and lush buffet dinners contrast sharply with the stories shared. There are monuments and cemeteries to visit (15,000 young Americans never made it back one vet says.) A great number of school children participated, with Charlotte commenting on how little American school children know in comparison to their French counterparts.

Charlotte herself sometimes appears on camera, such as when she is called upon in a ceremony or is talking with Don, who refers to her as his granddaughter. (She also serves as the film’s cinemaphotographer.) Also participating is historian Joe Balkoski who wrote the definitive history of the 29th Division, 116 Regiment. He and French guide Michael Yamaghas show the group the area where hedges tower over the roads, giving them their name of “sunken roads.” So difficult was it to see the dug-in Nazis that during the intense fighting to dislodge them there were more casualties than on Omaha Beach. The group marvels that they can still see the foxholes that the men had been forced to dig for shelter and protection 70 years ago.

The many stories are enhanced by numerous battle field drawings and archival photographs and newsreel clips, plus the expected maps of the beaches. We can see for ourselves how devastated was Saint Lô by the savage fighting, hardly a building left standing, reminding us of the fate of Ukraine’s Mariupol today. The quiet, melodious music of Jordan Plotner and Mark Suozzo heighten the emotion at key points.

It is obvious that the trip had a huge impact upon the young filmmaker, and she, greatly aided by editor Mark Juergens (a relative?), enables us to enter into the significant lives of those who risked so much on that deadly day. I was especially interested in the film because I was a little boy celebrating my birthday on that June 6. While I was blowing out candles, these valiant men, of whom I was not aware of, were fighting for their lives in the world’s greatest struggle against a barbaric tyranny. Charlotte Juergen’s film is a fitting tribute to these brave men without any flag-waving or glorification of war. Watching her film is a good way to commemorate their sacrifices on that awesome (and awful) day.

This review will be in the June issue of VP along with a set of questions for reflection and/or discussion. If you have found reviews on this site helpful, please consider purchasing a subscription or individual issue in The Store.