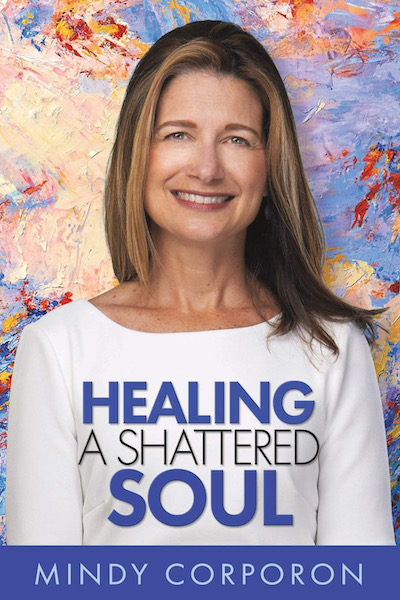

AS POSTED ON FACEBOOK Friday, July 12, 2024

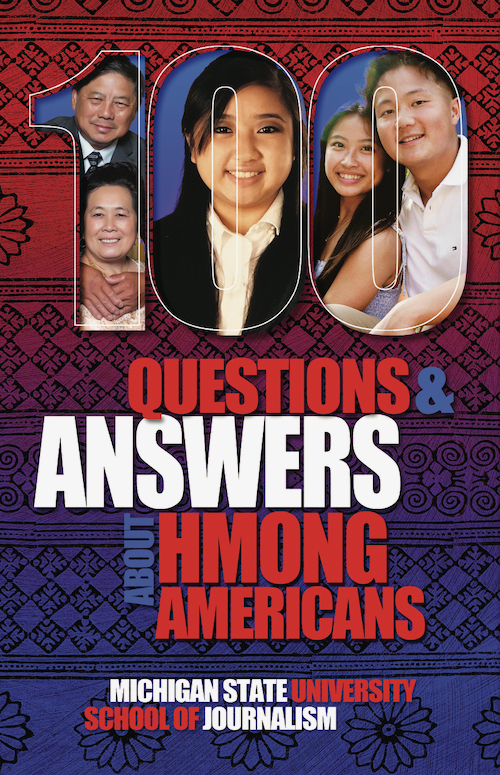

With the Michigan State University Bias Busters, we are celebrating the Hmong among us!

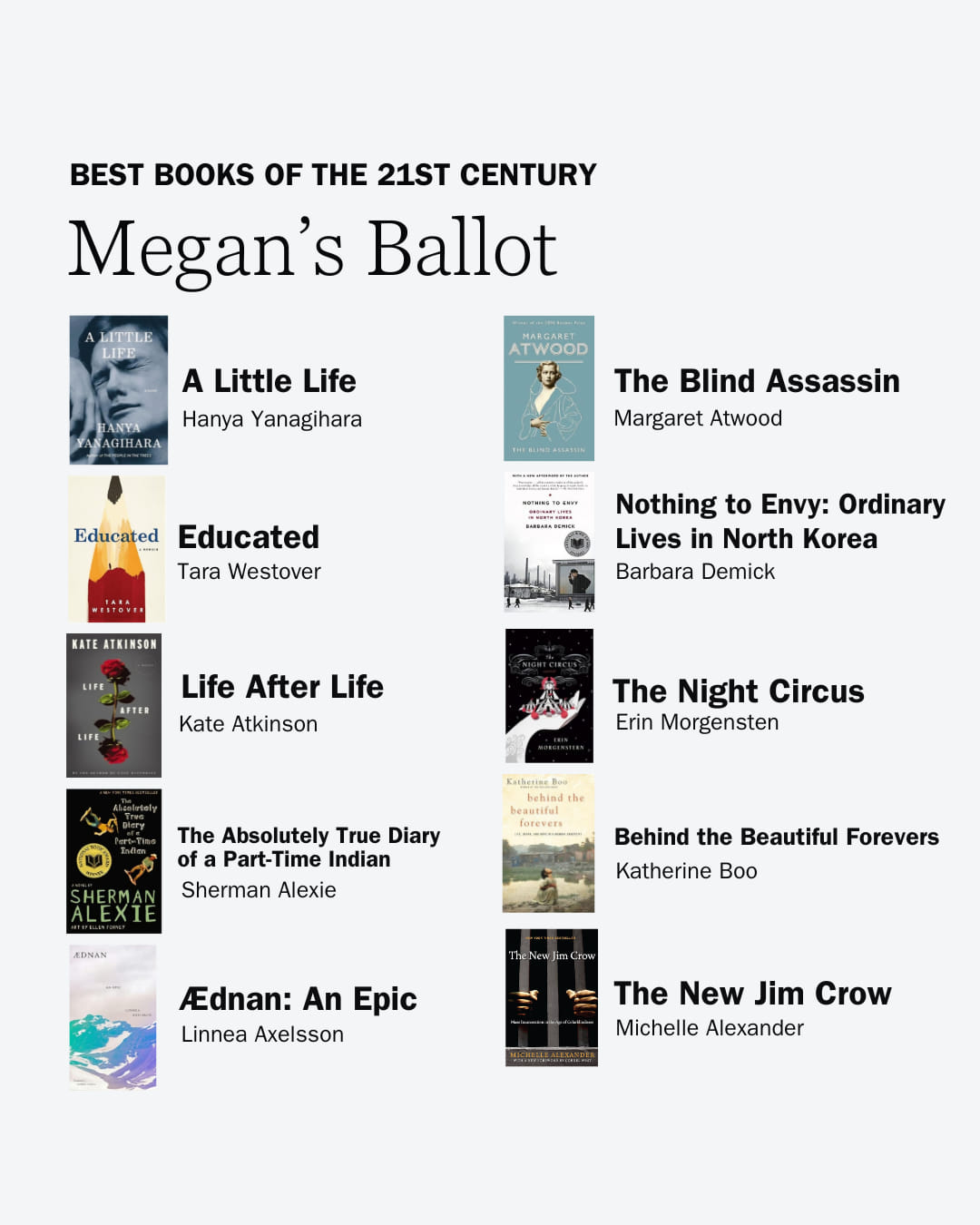

Click on this cover to visit the book’s Amazon page, where you can pre-order a copy to arrive on July 2, 2024.

Community Contributions of these Resilient Survivors are ‘Secret No More’

In fact, Secret No More is the subtitle of this new 100 Questions and Answers book from the Michigan State University School of Journalism Bias Busters project.

“Hmong Americans have traveled a long way in a very short time,” says the Preface to the newest volume in this award-winning series of books used nationwide to help reduce bigotry through education—in both text and video formats, in this case. As the Preface explains, “Very few Hmong people lived in the United States until its 1975 pullout from Vietnam. That put Hmong people, recruited by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency to fight in a secret war against the Viet Cong, in grave danger.”

This newest Bias Busters book will ship soon from Amazon, so please read (and share with friends via social media) this story (and videos) about the new book. Let’s collectively spread awareness of this remarkable yet little-known minority among us.

As the war was ending, thousands of Hmong were killed; thousands were evacuated to the United States to build new lives. They came from Southeast Asia and were scattered among states including California, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan and North Carolina.

Most Hmong people arrived with only what they could carry. They had little formal education, savings, warm clothing or any connection to these new places. Their English was limited. Return was impossible because the nomadic Hmong people did not even have a homeland. As Joseph Yang, one of the people you will meet in this guide, said, his people have had to “carry our culture and our religion on our backs.”

Now, in fewer than 50 years, Hmong Americans have traveled further still. Today, this population has very high rates of U.S. citizenship. They are succeeding in college, business, government and the arts. They have been elected or appointed to local, state and federal offices. They are judges, doctors, college students and professors. Many work in agriculture, as their families did in Southeast Asia before they were recruited to fight. Others work in U.S. health, education and media.

Hmong artists have enriched the tapestry of their new country with traditional music, song, poetry and visual arts. Some are excelling at U.S. forms of writing, dance and music.

But, to this day, Hmong people are little known, so this new book is a perfectly timed opportunity—as the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War approaches in 2025—to learn about these resilient survivors who are contributing in so many ways to American life.

First, how did the Hmong people get out of Laos?

Here’s one of the videos included in this book (accessible through QR codes in the book’s pages). In this short video Julie Xiong explains how Hmong people escaped from Laos.

How are Hmong families organized?

Julie continues in this short clip about the strong family networks that are an essential part of Hmong communities.

A unique cultural archive: ‘Story cloths’

In this video, Joseph Yang explains a bit about Hmong story cloths at an “Ask a Hmong” event held to spread news about this upcoming book.

Why are coins worn on traditional Hmong clothing?

Joseph continues with a brief description of this custom.

Care to learn more?

The Michigan State University School of Journalism Bias Busters project has produced about two dozen volumes in this award-winning series. Each volume is prepared by student-reporters who research 100 common questions people ask about each of the minority groups featured in a volume. Their work is overseen, in each case, by national panels of noted experts who work with the students to ensure the accuracy and balance of each book.

“In these books, we answer the questions every is asking—but no one is answering.” That’s been one of our guiding mission statements since we started this project. These guides are not in-depth histories. They are intended to provide basic information for Americans who want to understand more about our friends, neighbors and co-workers.

Please, share this story with friends to help us continue to foster this mission to help Americans understand each other in these often turbulent times.

Want to see all the guides? Here’s a link to Amazon’s overview page. (Note: The Hmong guide will appear in that list after its July 2, 2024, publication date.)

And once more, here’s a direct link to order the Hmong guide, which will arrive July 2.

Have a meaningful Memorial Day! And, consider these tips for conversations with veterans.

By JOE GRIMM

Director of the MSU School of Journalism Bias Busters

Memorial Day, the last Monday in May, is a federal holiday that honors U.S. service members who have died in wars and military actions. The millions of living veterans who have served have a different federal holiday: Veterans Day. That is always on Nov. 11—and recognizes Armistice Day, the end of fighting in World War I at 11 a.m. on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918.

Our entire community of authors, columnists and editors at Read the Spirit magazine is grateful for service members past and present. So, the first purpose of this column is to explain the difference between these holidays.

It is only natural that, as you encounter veterans around Memorial Day, you might want to recognize them for their service. But Memorial Day is to remember those who have died.

According to the Veterans Administration, there were 18.6 million U.S. veterans in 2023. Each year, about 200,00 people transition from active duty to civilian life.

When we thank military people, the gesture is filled with goodwill. That’s a good thing. But when we don’t know their personal experience, this can sometimes lead to misunderstandings.

Misunderstandings?

Think about it for a moment: One person’s military service is not like everyone’s service. Some prefer to talk about this; some prefer to remain quiet about it. Think about those veterans who sometimes wear their service like a badge on their sleeve, lapel or hat. It may seem like they’re actively advertising their service in the hope of sparking conversations. However, many who wear those badges on caps or coats explain that they wear them not to brag, but just in case someone else from their branch or unit might spot the symbol and reconnect. Those connections can be strong, even among people who have not met before.

So, rather than a hit-and-run thank-you, engage people if they are open to it. Rather than thanking them, ask a small question that shows you recognize the complexity of military service. An expression of interest can say more than a thank-you.

Maybe start with: “I see you are a veteran.” And watch the response.

If it’s welcoming, you might ask: “Which branch did you serve in?”

“When did you serve?”

“Where did you serve?”

These straightforward questions signify recognition and respect, but even they can uncover sensitive areas. They might surface painful memories or regrets. If they want to tell you more, you will learn something about their individual experience. If they don’t, that is OK. At least you took the time to look beyond the label to see the person.

Good starting points for learning about veterans—on any day of the year—are in “100 Questions and Answers About Veterans,” a guide in Michigan State University’s series on cultural competence.

This one describes the branches of the U.S. armed forces, what members are called, training, transitions, deployments and even a little military slang.

Jonathan Grimm on Andrea Longton’s new book: Making more money isn’t the only value driving us to invest

EDITOR’s NOTE: This week, we are publishing two stories to introduce an important voice in the national conversation about Social Justice Investing: Andrea Longton—a nationally respected expert in this growing field of finance that encourages people to exercise their spiritual and ethical values while investing their money. This is such an important area of interest for our long-time ReadTheSpirit readers that we providing two perspectives on Andrea’s work:

In this story, below, we asked financial expert and author Jonathan Grimm to provide his persective on Andrea’s new book.

By JONATHAN GRIMM

Author of The Future Poor

(coming from ReadTheSpirit Books)

.

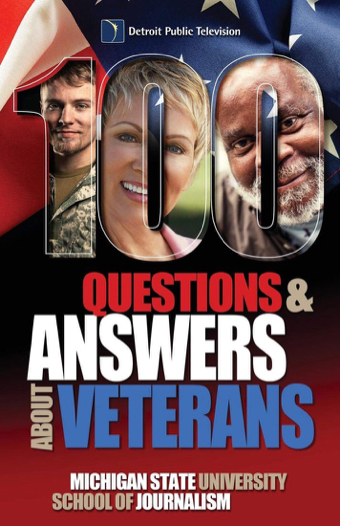

The Social Justice Investor, by Andrea Longton, is an important introduction to the world of doing good with your investments while building wealth.

Yes—you can do both!

These used to be seen as mutually exclusive endeavors, building wealth and doing good with your money, but that is not the case anymore for this generation of investors.

Many turned to ESG (environmental, social and governance) funds, which have served as a placeholder for ethical investing. But there has been an unwinding of these funds by most major investment firms over the past year. This is due in part to the increased politicization of ESG and profitability has not always been there. When a fund doesn’t perform it becomes one of the over 400-plus funds that close in a given year.

Their goal is to make money, right?

It would seem that way, but if we don’t have an easy “boxed” solution for what so many investors want that actually works, where do we go?

Michael Lewis, one of my favorite financial writers, had this helpful insight in his book Moneyball. “What begins as a failure of imagination ends as a market inefficiency. When you rule out a class of people to do a job because of their appearance you are less likely to find the best person for the job.”

For social justice investing we need our imaginations! We must think outside the box! That is what we are exposed to in Andrea’s new book. What she shows us, over and over again, is that those who do find creative solutions, and make it happen, change the world for the better.

As an Investment Advisor myself I’m recommending this book because far too often conversations about money revolve around potential risks and rewards for ourselves and our clients. One of the most eye-opening reasons to read Longton’s new book is to come away realizing:

“Getting rich is not the only way to think about investing. And—wow! A growing number of people actually are doing this. They’re taking seriously their values of goodness, compassion, justice and a general concern for the world’s welfare in deciding where to put their money to work.”

That certainly struck me as I read her book. I thought: I want to recommend this to people as a wonderful way to learn about other people trying to do this—and the nuts and bolts of how they’re actually doing it. The book is not only inspiring; it’s a “how to” manual as well.

It may put Wall Street and the old investment advisors on their heels. They’d be wise to pick up this book and prepare for the new way people are wanting to invest. I certainly am recommending it to my colleagues.

We want to be happy with growth and the way we got it. This is refreshing and has left professionals like me having to figure this out—and there aren’t a lot of resources out there.

Perhaps it is time to start to shrug off some of the old “wisdom” and adopt more socially conscious approaches to finance as Longton writes, “Wall Street culture isn’t working for us.”

Far too often we have been narrow minded in looking at returns. 12% is better than 10% which is better than 8%. But today’s investor sees this as only one variable important to investment returns.

Today’s generation of investor says the following and perhaps you are too:

“I want my investment growth to improve the lives of others.”

“I want my investments to be in something that helps the environment.”

“I want my investment to further break down barriers across gender, race or class.”

There is helpful language throughout this book that you can use as you start investing—and language you can use with your financial advisor about how to begin.

What I have come to realize is that just as there are fees and taxes on an investment that reduce its overall effectiveness, the social justice aspects of our investing carry “taxes.”

Today’s investor sees a tax on their return if the 10% growth created a larger carbon footprint. It may not show up on a balance sheet but it certainly shows up in the human calculation we are running inside.

Similarly, investors place non-dollar premiums on the investments that do social good and align with their values. We each weigh that value differently but a 6% return with a premium-added-value of affordable housing or financing for those who do not pass the institutional “eye-test” is of significant value. Sometimes, it even generates greater actual returns!

You and I have particular social issues that would give us the greatest premium return on top of our investment growth and I encourage you to seek out those opportunities.

It isn’t simply on the individual level. I have been part of projects that raise over a quarter million dollars in a day from a local community in order to directly serve the foster care system.

I can tell you firsthand, that is investing magic! If you are unsure, give it a try and see how you feel.

As someone who has an educational background in ethics and philosophy and currently works as an Investment Advisor, I rarely see these two worlds come together and it is refreshing when they do. Often projects lean to the ethics side without real-world financial solutions. Or, there can be a disconnect between the professional financial advice offered and the experiences and needs of those to whom it is offered.

This has been a focus of mine for the past four years as I am working on a book, like Longton’s, that is focused on bringing these two important realms closer together. While The Social Justice Investor looks at ways to use our investments for social good, my upcoming book is focused on how we keep the current generation off a path of future poverty in retirement. In many ways, these are topics that link arms and walk together in the continued fight for the dual effort of good finance and social justice for all.

I am grateful for this important contribution to the national conversation and hope to continue to work with Andrea and others as these concerns expand.

As hate crimes continue to rise, this inspiring documentary about two courageous mothers—Mindy Corporon and Sunayana Dumala—is Must See TV

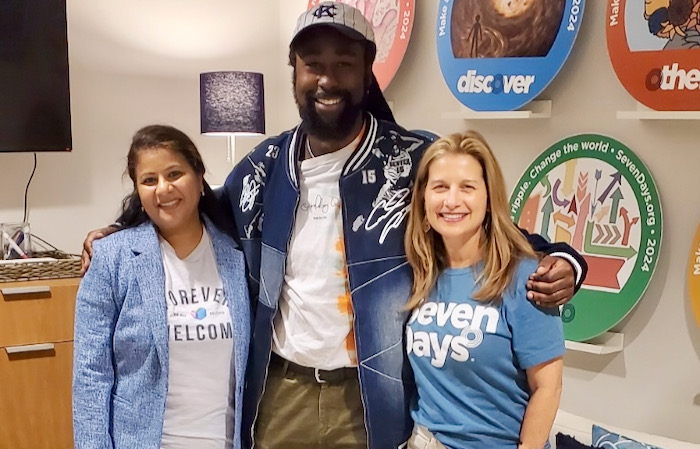

Three key people behind this new public TV documentary, Healing Hate, are from left: Sunayana Dumala, Solomon Shields and Mindy Corporon.

“Hate has no place—because it will touch everybody.”

Mindy Corporon in the documentary Healing Hate

“But both Mindy and Sunayana and their families used the worst days of their lives to empower them to engage the world in positive ways.”

Documentary filmmaker Solomon Shields

See this powerful documentary right now:

Right now, you can learn more about this documentary, created by Kansas City PBS along with filmmaker Solomon Shields, by reading our ReadTheSpirit cover story below.

But, first: Thanks to Kansas City public TV’s YouTube channel, you also can stream the entire half-hour documentary here:

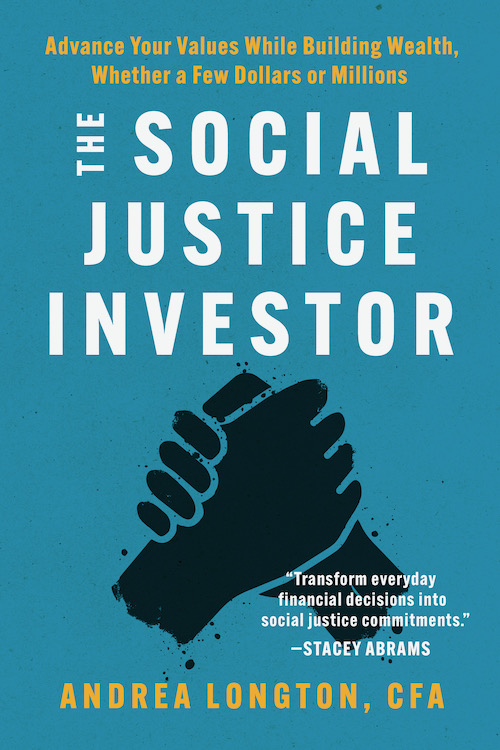

To read Mindy’s entire story, including how she met her friend Sunayana—get a copy of Healing a Shattered Soul in hardcover, paperback or Kindle via Amazon.

‘Healing Hate: Turning Pain into Power’

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit online magazine

After weathering some of the most horrific hate crimes in America over the past decade—including a catastrophic mass shooting at a parade in February—Kliff Kuehl, the CEO of Kansas City’s PBS station, and filmmaker Solomon Shields committed themselves to arousing public action.

As the resulting 30-minute film debuts this week, Kuehl is telling viewers, “Kansas City PBS is honored to bring Healing Hate to our viewers. This documentary has the potential to inspire and ignite a collective commitment to stand against hate, fostering a more inclusive Kansas City,”

The film’s power springs from the stories of two women who have transformed their grief over losing family members, killed in earlier shootings, into major ongoing efforts to promote compassion, healing and inclusion.

The first of these two friends is author and nationally known advocate for community compassion Mindy Corporon, whose son and father were killed 10 years ago in an antisemitic hate crime outside the Overland Park, Kansas, Jewish Community Center in 2014. Mindy has published the widely read memoir Healing a Shattered Soul and also is co-founder of the nonprofit community movement known as SevenDays.

Mindy’s friend is Sunayana Dumala, who Mindy met in 2017 after national news broke about the murder of Sunayana’s husband by a shooter in an Olathe, Kansas, restaurant. The murderer declared that he wanted to kill someone from the Middle East—and that he thought his victims were Iranian.

“I worked a lot of long hours with Mindy and Sunayana and many others on this project because all of us know how timely this documentary is,” Solomon Shields said in an interview this week.

The urgency they all feel this spring includes the latest mass shooting at the Kansas City parade—as well as national reports that hate crimes are rising to an all-time high, plus the upcoming April 13th 10-year anniversary of the antisemitic shootings that killed Mindy’s loved ones.

“All of us felt we had to share this documentary with as many people as possible—right now,” Shields said.

What’s so horrifying is: When bullets fly—they can hit anyone

“What’s so astonishing is that in all three tragedies—the gunmen were coming from a place of anger and violence that wound up killing people who they never intended to kill,” Shields said. “That’s one of the main themes of this documentary: When bullets fly, they can hit any of us.”

In 2014, Mindy’s son and father were in a parking lot preparing to participate in a community program being held inside the Jewish center—but they were not Jewish. In 2017, the shooter in Olanthe was raving about Middle Easterners and mistook Sunayana’s Indian-American husband for an Iranian, according to news reports. And, in February 2024, the one death and 22 injuries were caused by several armed young men who opened fire at each other in a personal dispute that had nothing to do with their 23 innocent victims.

“We have to realize: When guns are blazing and bullets are flying, those bullets don’t care what you look like or who is waiting for you at home,” Shields said. “It’s so important for people to understand that we all must take steps to prevent this from happening to others.

“This is definitely something that hits close to home for me as an African American filmmaker,” he said. “I have had friends who have lost their lives to gun violence: wrong place, wrong time and a bullet happens to hit them. I was very honored to work on this project because it’s something I can relate to. I remember both of these earlier shootings and they had a real impact on me.

“The main theme of the documentary is how these two families overcame such unspeakable tragedies so that they could continue to live and build relationships. That’s the flip side of this documentary: Even after such tragedies, we can decide to build relationships that can make our entire community better.

“I am so impressed by the strength of the human spirit in these two women who were able to face the world again after the worst days in their lives,” Shields said. “For a lot of people faced with this—it would have been understandable to simply say: We need our privacy and refuse to talk to anyone anymore. But both women and their families used the worst days of their lives to empower them to engage the world in positive ways.”

That took an enormous amount of emotional strength within these families—as readers learn when they read Mindy’s memoir. In this new public TV film, viewers also will see and hear these two friends talk about that process of transforming anger into hope.

Shields said he continues to be amazed at their strength. “I realize that they may not ever have a perfect day again after such tragedies—because every day they will remember the loved ones they lost. That’s why this film is so inspiring. These women chose not to close themselves off to the world. They decided to show the rest of us that there is still life worth living, if we can work on these issues together.

“When people see this documentary, I want them to come away, first, feeling informed about all the reasons this is such a timely message. Second, I want viewers to feel inspired that, even though these horrible things continue to happen, there are relationships we can form that can help us, our families and our communities—that is, if we are willing to search for those new relationships.

“Finally, I want people to feel that there are things they can do whoever they are and wherever they are,” Shields said. It’s a lesson he took to heart as he worked with these families and the Kansas City PBS staff to produce this film. “That’s what I could do right now. I’m a filmmaker here in Kansas City and I did something: I created this documentary that can share this story with so many people out there. And, now, I appreciate that others are out there trying to encourage more people to see this film.”

And one last reminder …

Wherever you live across the U.S., you can contact your local PBS station and urge the management to seek out this documentary to broadcast in your region. If you have never done this before—simply find the website of your “local” PBS station, contact station management through their website and share a link to this story. Most public TV stations appreciate local viewers making such recommendations.

To read Mindy’s entire story, including how she met her friend Sunayana—get a copy of Healing a Shattered Soul in hardcover, paperback or Kindle via Amazon.

Redrawing the history of ‘comic books’ and celebrating the creative joy of all ‘outsider’ artists

Could a family member or neighbor be an unheralded light in our world?

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

In my half century as a journalist covering religious and cultural diversity, I have profiled hundreds of “outsider” artists whose unique creations in music, visual arts, filmmaking, poetry and sculpture have been a rich part of global cultures for thousands of years. I am continually looking for those overlooked men and women who are spreading joy—or are sharing their laments—through whatever art-forms they can envision.

I once profiled an Appalachian artist who constructed his entire two-story home to look like a gigantic duck (covering the entire duck-shaped home in shingles that looked like feathers) as his tribute to the birds he loved. In Asia, I profiled an artist who created an enormous shrine to his ancestors made entirely of seashells and beautiful stones he found along the ocean shore. I profiled an Appalachian coal miner who recreated the entire book of Genesis in wood-carved tableaux that eventually wound up at the Smithsonian. And, perhaps my personal favorite: I profiled an Appalachian woman who fashioned musical instruments from gourds so that she and her friends could play gospel tunes.

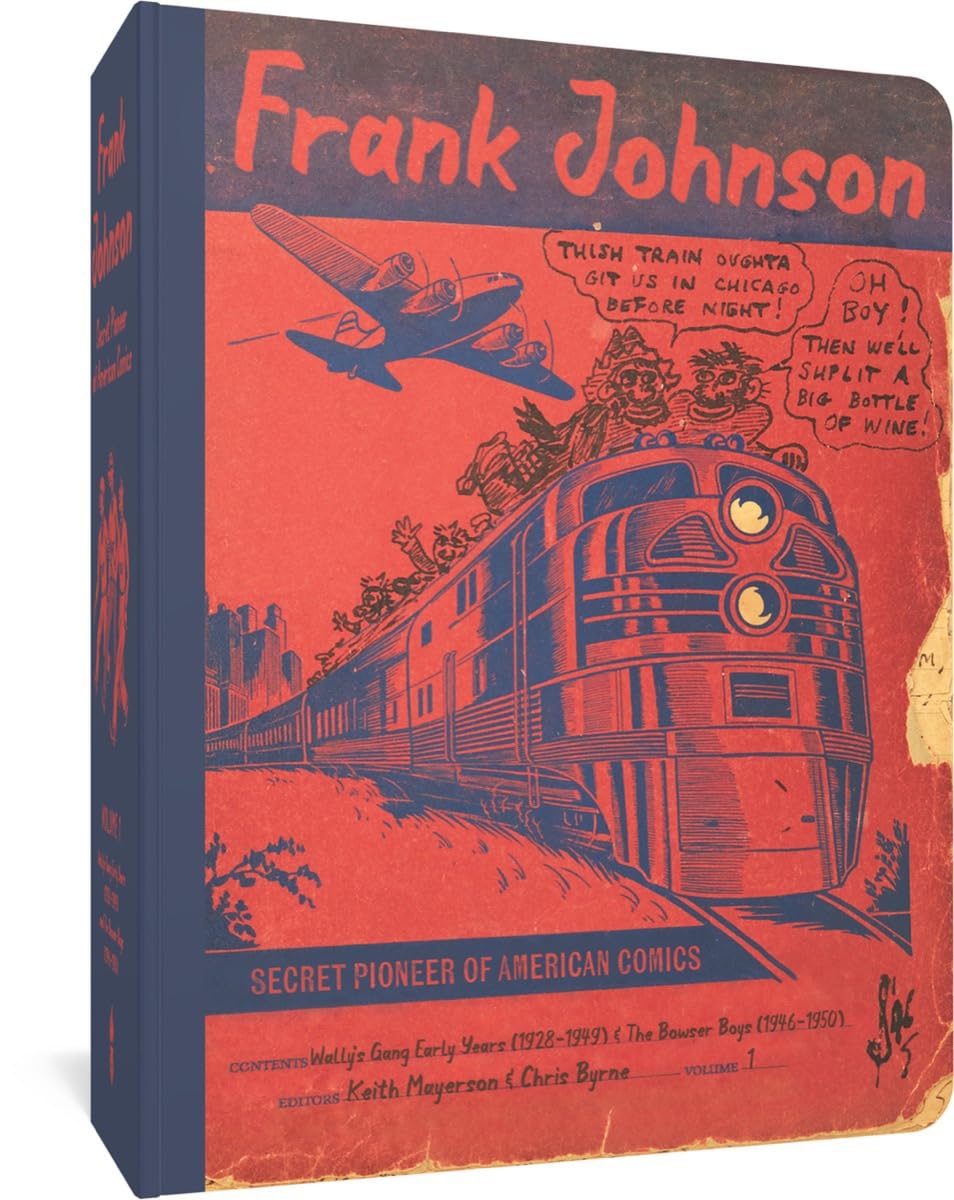

So, you can see right away why I was so eager to read and review this beautiful, fascinating, 634-page tribute to the comic books created by the until-now-unknown comic pioneer Frank Johnson. The debut of this selection of Johnson’s comics now will redraw our official history of American comic books. That will take some time, but that rewriting is sure to come—especially since this book was produced by the highly respected Fantagraphics and includes extensive opening essays by curator and historian Chris Byrne and fine artist and graphic novelist Keith Mayerson.

At this point, though, Frank Johnson does not even have a Wikipedia page—although that is certain to change over the next year or so. And Wikipedia still sums up the official history of American comic books pretty much like all the other history books, to date:

The term comic book derives from American comic books once being a compilation of comic strips of a humorous tone. The first modern American-style comic book, Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics, was released in the U.S. in 1933 and was a reprinting of earlier newspaper humor comic strips, which had established many of the story-telling devices used in comics.

This new Fantagraphics volume contains examples from half a century of the comic books Frank Johnson drew in blank, bound notebooks that were available in stores for students and office workers from the 1920s until his death in 1979. In other words, Johnson was creating full-fledged comic books a decade before Famous Funnies. His own private creative instincts led him to envision, plan, write and draw what is now considered an important American art form—years before there was any example on the market.

What could possibly have kept Frank Johnson going for so long in this private pursuit?

Minnie Black’s All-Gourd Band: ‘A Joyful Noise Unto the Good Lord’

I remember interviewing Minnie Black, the Appalachian gourd artist who created an entire band’s worth of instruments from gourds. She eventually appeared nationwide on radio and TV and had a sampling of her work collected by the Smithsonian—but in her early years as a gourd artist, her friends thought she was a bit eccentric even by Appalachian standards.

“Minnie, you created the first all-gourd band anyone has ever heard,” I said. “What made you think of this? And what kept you going even when no one seemed interested, at first?”

“I just wanted to make a joyful noise unto the Good Lord and I saw a gourd one day that was shaped like a dulcimer—and the next thing I knew, I was seeing gourds that looked like other instruments, too,” she said.

Minnie was a full-fledged artist—the Smithsonian would call her a “folk” or “naive” artist—for years before the world discovered her body of work.

‘Cautionary humor’ about life’s great challenges?

What’s so fascinating about Johnson’s body of work, beyond his pioneering creative vision, is that—like Minnie Black’s gourds—his comics reflect the challenges of his life.

The book opens with selections of Johnson’s Bowser Boys comic books, whose “heroes” are a group of homeless alcoholic friends who pursue booze with clever twists and turns every day of their lives. They rise to the challenges of daily life—even though their clothes are rags, they are covered in grime and Johnson draws them with flies buzzing around their heads.

As it turns out: At one point in Johnson’s real life, he was an out-of-control alcoholic himself and clearly these comics are a kind of wildly satirical exorcism of that raging addiction. Eventually, he became a devoted member of AA, but that era seems to have remained in his mind and heart for the rest of his life. We don’t know for sure, because Johnson left few biographical details when he died, but these comics could have been cautionary humor to share with friends Johnson got to know at his AA meetings. Perhaps some surviving friend will surface, now that Johnson is receiving more publicity, to fill in that biographical gap.

However, the majority of this book focuses on his decades-long Wally’s Gang series of comic books. This series feels like a first cousin to Archie and Gasoline Alley: a small-town gang of friends forever facing challenges in their relationships—and often pulling pranks on one another.

Some outsider artists—notably Minnie Black, who eventually appeared on Johnny Carson’s late-night talk show—attain a measure of fame in their lifetimes. In fact, I helped with her ascent into the public eye as a journalist, publishing one of the first major profiles of Minnie for a national wire service in the 1970s. She thoroughly enjoyed all the attention she received until she eventually died in 1996 at age 97.

But far too many “outsiders” only shine posthumously. Keith Mayerson captures the bittersweet truth of Frank Johnson’s career in this haunting line: “Frank Johnson laid out the future of comics for an audience of no one.”

No one was aware of his astonishing lifetime output until his descendants realized there was value in all those notebooks he had stored away.

If you would like to glimpse what the other kind of outcome for an American outsider artist can look like, you can watch a marvelous 4-minute video of Minnie Black uploaded to YouTube in 2023 by the Appalshop Archive.

For Frank Johnson, the creation of his body of work was enough to keep him going for many decades. The sheer joy he found in creating these stories is obvious in the glee shared by members of Wally’s Gang. And, now, his family can celebrate the true creative genius of their patriarch.

And—Here’s Minnie Black

Jeffrey Munroe and Nicholas Wolterstorff: ‘A book so meaningful, strangers tell others to read it’

EDITOR’S NOTE: “It’s a book so meaningful, strangers tell others to read it.” In 17 years of publishing books, we can tell you: That’s the highest praise an author can aspire to earn. Since our founding in 2007, our authors have shared our mission: “Good media builds healthy community.” That happens when strangers feel compelled to spread the good news to others. Jeff Munroe’s new book, Telling Stories in the Dark, is receiving that valuable word of mouth. In this column, Jeff writes about one of his mentors who impressed him in this same way.

Meeting an author whose life and books have shaped my own

By JEFFREY MUNROE

Author of Telling Stories in the Dark

Sometime in the 1980s, I attended a discussion about dismantling Apartheid, the South African system of discrimination and segregation that allowed a non-White minority to rule that country. One of the speakers was Nicholas Wolterstorff, a professor of philosophy at Yale University. Wolterstorff was joined by Alan Boesak, President of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, a black South African who had very few civil rights in his own country. Their conversation was enthralling, and after the event I walked into a pop-up store that featured books by the authors.

Nicholas Wolterstorff’s books were on topics like art and aesthetics, reason and religion, and justice and peace. I suspected they were beyond me. (No one was going to suggest I study philosophy at Yale.)

Amid these weighty tomes, there was a small book called Lament for a Son. When I picked it up, a stranger leaned over and said, “Oh, you’ve got to read that one.” As I experienced, it’s a book so meaningful strangers tell others to read it.

Wolterstorff had lost a son in a climbing accident a couple of years earlier. Lament for a Son was a full-throated cry of anguish, sorrow, and grief. I took it home, read it in a day, and then read it again. I’ve read it five or six times since—it’s one of those books I keep returning to. There is great comfort in Wolterstorff’s words. He hadn’t put aside his great intellect to write the book, but there was nothing academic or intellectual in an off-putting way about it. It was thoroughly human and riveting and it is a book I treasure.

Fast-forward more than 30 years: As I was working on my book Telling Stories in the Dark, a book about people who have not only faced great loss but have done something redemptive with their loss, I thought of Nicholas Wolterstorff. I wondered if I might interview him for my book. I knew he was about 90, but had a mutual friend who told me Wolterstorff was still at the top of his game. I asked the friend if he would introduce us through email, and, as it turned out, Wolterstorff was happy to talk with me and be in my book.

The pandemic was winding down, so I used Zoom for the interview, which also gave me an easy way to record our conversation. The first thing the distinguished Professor Nicholas Wolterstorff did was insist I call him Nick. Then he mesmerized me as he spoke not only about the loss of his son but of living with this loss for decades. I knew our conversation was going to be very helpful for others.

When the interview ended, I shut down Zoom and waited for my computer to tell me it was storing the recording. Nothing happened. After a few moments of panic, I realized I was so excited about interviewing Nick—I had never hit the “record” button. (I might have said one or two bad words at this point.)

I quickly wrote down everything I could remember—thankfully, I had my list of questions, so used that as an outline. Then I decided the only thing to do was come clean. I decided to go back to him, tell the truth (leaving out the part about messing up because I was nervous about talking to one of the gods on Mt. Olympus), and hope for the best.

He was incredibly gracious. He offered to do the interview again, and also offered to send me some additional things he’d written as background. I used what he sent, augmented my notes, and then sent what I had to him.

He wrote back almost immediately, gave me a few corrections, and told me it was “excellent.” (For a second, I thought maybe I should have studied philosophy at Yale after all.)

I am profoundly grateful that we know each other. Nicholas Wolterstorff is one of our most distinguished philosophers. He has been invited to lecture at virtually every prestigious university in the world. Yet the other day, when I visited his church to lead an adult education class on sorrow and grief, he not only welcomed me enthusiastically—he walked me through the large building so I arrived where I needed to be.

He and his wife sat in my class and expressed gratitude that I had told their story well. His humility and authenticity are remarkable.

And so is his story, which I am exceedingly proud makes up Chapter 9 of Telling Stories in the Dark.