By DAVID CRUMM

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

Today, a growing number of Americans agree that the so-called Emancipation Memorial in Washington D.C.—and its duplicate in Boston—need to come down. City officials in Boston already have removed their copy. The fate of the D.C. original has not been determined.

Why such a strong consensus? Because—as Lincoln scholar Duncan Newcomer writes this week—almost certainly, Lincoln himself would never have wanted that image as his legacy. Lincoln did not want anyone kneeling before him—and said so!

Then, how did this become such an icon? As Duncan points out, statues are external expressions of artists’ perspectives on historic figures and events. In most cases they are erected after a hero has died and are not—by their very nature—an expression of that person’s inner soul. They are biographical, not autobiographical. And among biographies, most memorial statues would fit in the genre “hagiography,” stories of saints by those who adore them that are infamous for their inaccuracies.

.

What Was Frederick Douglass’s Perspective?

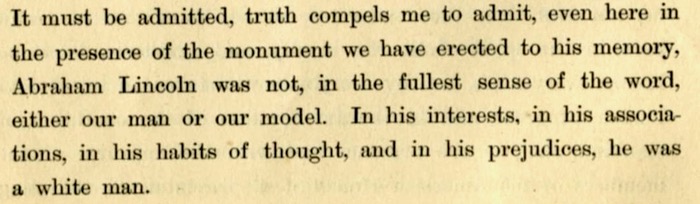

In recent arguments for the removal of Thomas Ball’s original sculpture in Washington D.C. and its duplicates, many commentators quote a couple of lines from Frederick Douglass’s dedication of the memorial in 1876. Douglass’s lengthy oration has been preserved online by the Smithsonian and it is well worth reading in its entirety, because Douglass eloquently indicts Lincoln for moving toward emancipation mainly as a last-ditch weapon in his effort to defeat the South.

Douglass makes crystal clear in that 1876 oration that Lincoln was a “white man” living with the biases that were so common among white Americans.

What most commentators fail to add is that Douglass stressed Lincoln’s biases—in order to express how amazing it was that Lincoln, despite those prejudices, nevertheless made the astonishing decision to end the institution of slavery.

As his oration built toward is challenge to continue what Lincoln had begun, Douglass called on White Americans to lift up Lincoln’s model to future generations. White Americans should embrace both their identity as Lincoln’s “children” and the new role of Black Americans as Lincoln’s “step-children.” Speaking for Black Americans to White Americans, he declared: “We would exhort you to build high his monuments.”

Whatever Lincoln’s complex rationale was for ending slavery, the fact is that history was transformed at that moment—and White Americans must find the courage to continue down the path Lincoln had opened, Douglass argued. Reading the entire text of Douglass’s oration that day, it is obvious that he had little praise for the actual statue. Douglass’s oration was, at best, a pragmatic endorsement of the image as a small step White Americans were taking to move further along the path Lincoln had opened for the nation.

Today, there is no question: The Thomas Bell monument was a tragically conceived image of a powerful White figure dominating a groveling Black figure. Black Americans objected to its depiction even in 1876.

That is why Boston removed its copy of the memorial. Meanwhile, so many other monuments are falling in the wake of George Floyd’s killing that Wikipedia has a huge page devoted to listing them all, including the June 30 removal in Boston.

(The other Lincoln-related removal on the Wikipedia list is a stained glass window in the Cathedral of the Rockies, which will be removed because it shows Robert E. Lee standing with George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. The leadership of this United Methodist congregation that calls itself “Cathedral of the Rockies” had been discussing the window’s removal since 2015—and finally decided to take it down after Floyd’s death.)

William Edouard Scott Reverses Ball’s Image of Dominant Lincoln

A dramatic contrast to Ball’s image of a dominant Lincoln was a ground-breaking mural by Black artist William Edouard Scott (1884-1964). Scott graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was committed to developing positive images of Black Americans—especially in his depictions of Frederick Douglass.

A dramatic contrast to Ball’s image of a dominant Lincoln was a ground-breaking mural by Black artist William Edouard Scott (1884-1964). Scott graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was committed to developing positive images of Black Americans—especially in his depictions of Frederick Douglass.

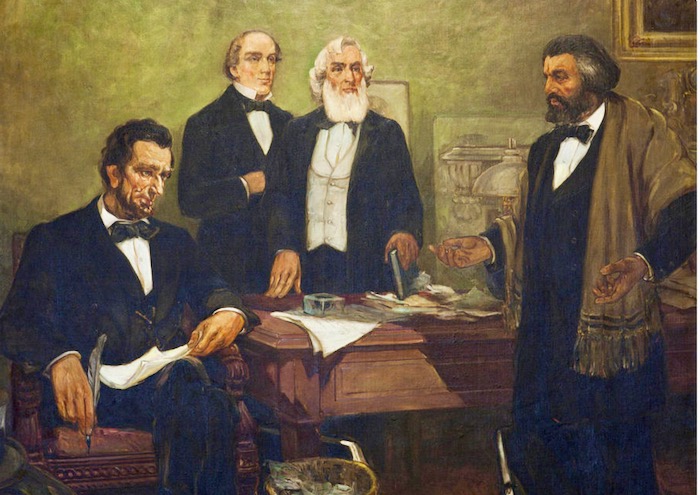

In 1943, Scott was selected as the only Black artist chosen to create a mural for the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C. He named the mural: “Douglass Appealing to President Lincoln.”

Frederick Douglass met Lincoln face to face three times. Scott’s mural depicts his first appeal to Lincoln in 1862 to combat discrimination in the Union army against black soldiers. The main effort to recruit black regiments began only after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in January 1863. No photographs were taken during that meeting.

African-American art scholar and curator Edmund B. Gaither, devoted part of a book about four Black artists to this particular Scott mural, writing: “Scott, in his manner of depicting the exchange between Lincoln and Douglass, suggests that the fiery orator is here the aggressive speaker. Whereas Douglass, hands extended slightly, shifts his weight forward while speaking to Lincoln, the president appears to avoid looking into Douglass’s eyes and concentrates on listening to his words.”

Furthermore, the strewn and scattered papers on the desk and around the trashcan suggest urgency and desperation—and this was certainly the case. “The Civil War was proving much more difficult than the Union leadership had expected.” And while Douglass presents a possible solution to the president, it is far from ideal in Lincoln’s eyes. Many whites of this time didn’t believe that African Americans could be effective soldiers. Regardless, Douglass is undeniably the active part of this depiction. This portrayal furthers the message inherent in the subject matter: African Americans could be equally as patriotic, and thus equally effective as soldiers, as any whites.