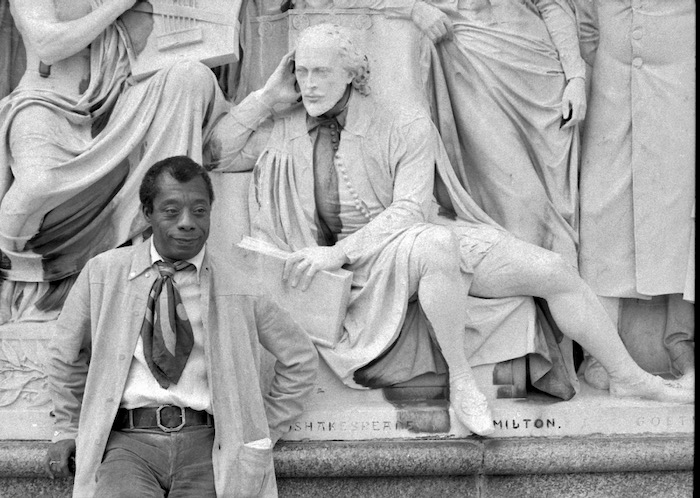

SOULS and STATUES—Throughout his career, James Baldwin explored the painful struggle of living with opposites, including despair and hope, injustice and compassion, truth and compromise. Throughout his life, Baldwin had little patience with the hyperbole of monuments, which is why he had an ironic grin as he agreed to pose with this statue of Shakespeare in central London.

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Author of 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln, and its relevance to us today. Welcome. This is Duncan Newcomer.

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you: “Don’t kneel to me. That is not right. You must kneel to God only, and thank him for the liberty you will enjoy hereafter.”

It is the morning of April 4, 1865, and Lincoln has made an inglorious rowboat landing from the James River in Richmond, Virginia, and is walking up the streets of the burning and defeated Confederate Capital. Most of the Whites, including Jefferson Davis, whose chair Lincoln hopes to sit in briefly, have fled. Excited gatherings of former slaves recognize Lincoln’s tall body and silk hat, and a man has fallen to his knees in front of Lincoln. People are calling him “Father Abraham.”

Lincoln has a truly humble heart and is a clear-minded theologian. He says: “Don’t kneel to me. That is not right. You must kneel to God only, and thank him for the liberty you will enjoy hereafter.”

Thomas Ball—the creator of the Washington, D.C., and Boston Commons statue of Lincoln—clearly had not heard what Lincoln was saying. But many of us, Black and White have heard. Today, we cannot abide the humiliation of the Black man on his knees and we sorely need the humility of Lincoln and his relationship to God.

Can we take a moment to listen better to Lincoln’s real words?

The great value of the Lincoln Memorial is that his voice is all around us in words etched into the walls: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Addresses and the Gettysburg Address. We can read. We can hear.

We know what Lincoln was saying: Don’t kneel to me. I have never pretended that I am a god.

If now a statue seems to say otherwise, Lincoln would agree: We should take that down.

Frederick Douglass at the 1876 dedication of the Washington D.C. statue in question said that it “showed the Negro on his knees when a more manly attitude would have been indicative of freedom.”

We can understand also why Douglass agreed to speak there, despite his misgivings. President Grant was there. Some of the Supreme Court was there. Much of Congress was there. And the statue itself was fully paid for, $17,000, by newly freedman’s money, the first being $5 from a young Black woman. Blacks paid for but Whites designed the statue.

So there were other voices speaking from that statue on that dedication day—and Douglass used the occasion to urge his White listeners to recognize that Lincoln had set them on a path they should courageously pursue.

That is why history is so nuanced and complex. There are many voices.

The “democratic mind” has been defined as one that can hold seemingly polarizing ideas—many differing, nuanced and complex voices—in its head at the same time. Not because it is confused, but because it is realistic.

As many episodes in the Quiet Fire series have shown, Lincoln certainly had a democratic mind. And, so have other great American sages, especially the poet, author and journalist James Baldwin. We cannot read Baldwin’s writings without glimpsing his dual mind and heart.

Baldwin’s dual-mindedness was there as he was growing up as a sensitive young man struggling to live in the world as it is. He needed to find some measure of love and hope in his heart, despite the cruelties, injustices and blindness he encountered everywhere he turned. He struggled mightily to find some solid ground between bitter despair and love.

He described a kind of double consciousness that Black people in America must master. Baldwin wrote that his sense of double mindedness was to “hold in one mind forever two ideas which seemed in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life, as it is, and men as they are….(and) the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in ones’ own life, accept these injustices as common place but must fight them with all one’s strength.”

This was his only way to “keep his own heart free of hatred and despair.”

For that reason, Baldwin rarely wrote about Lincoln. On the few occasions that Baldwin did address Lincoln’s legacy, he did so to attack White Americans’ mythic adoration of heroes like Washington and Lincoln. Baldwin agreed with Douglass that Lincoln’s role as savior of slaves was a morally compromised choice mainly aimed at saving the Union.

The subject of Lincoln was too painful for him to contemplate, Baldwin wrote in a 1982 essay. “I am weary of Lincoln Memorials, of the American piety, which is nothing less than a Sunday-school apology for genocide.” Baldwin was letting his readers see the depth of his despair with his nation’s centuries of injustice.

His essay continued: “The Republic is a total liar and has never contained the remotest possibility, let alone desire, to let my people go.” Baldwin warned his readers: Most White American heroes from Lincoln to the Kennedy brothers will break your heart if you look too deeply into their motives, their compromises, their limitations.

And yet it is our lot in life as Americans to grapple with these painful truths, struggling toward a hope that we are somehow stumbling forward. It’s a painful journey, Baldwin wrote. “To be a Black American is much worse than being in love with, tied to, inexorably, mysteriously, responsible for, someone whom you don’t like, don’t respect, and don’t dare trust.”

It is a lover’s struggle, Baldwin finally concludes. And this struggle is inescapable, if one truly is honest about the dilemmas in our history—and our future.

The irony is that, in the spiritual life of Lincoln, we find this same paradox: a struggle every day to hold together a sense of purpose in the midst of opposites that threatened to swallow up all hope.

Perhaps as a result of 2020, we may commit ourselves to spending less time gazing at someone else’s idea of a statue—and more time with the authentic voices of great sages like Lincoln and Baldwin.

Perhaps they may light a pathway so that we, too, can search for the humility, balance, hope and power that animated their lives.

.

.

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln