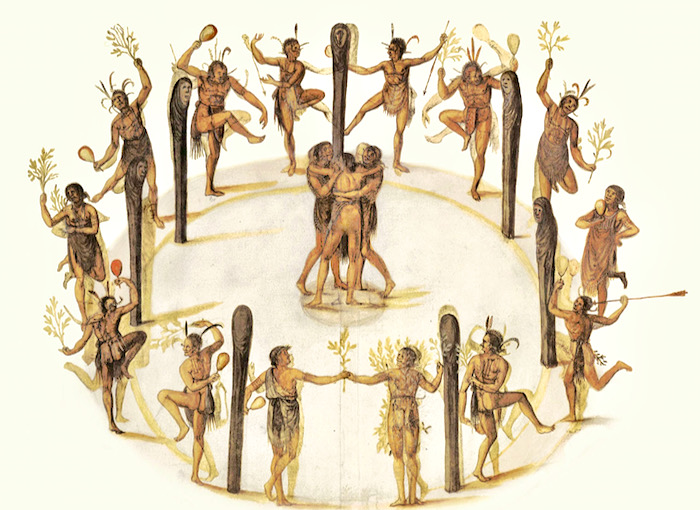

JOY AND HEARTBREAK—This 1585 watercolor painting of a traditional dance among the Roanac (spelled Roanoke by settlers) is both joyous and heartbreaking, because it is one of very few images we have of this Algonquian-speaking people who once lived in present-day Dare County on the far eastern coast of North Carolina. English visitor John White, an explorer, cartographer and artist made a series of watercolor illustrations in 1585 to accurately educate the British about Roanac culture. Today, his watercolors, including this one in London’s British Museum, are among the few traces left in the world of this once-vibrant community. (NOTE: This image is in the public domain and can be shared along with this story.)

.

Learning from Our Native American Neighbors, today

EDITOR’S NOTE: This year, our magazine is highlighting emerging stories about our relationships with our Native American neighbors. We have been reporting on both the tragic challenges and the multi-faceted opportunities, right now, in establishing such cooperative relationships. As residents of North America, today, we have an enormous amount of work ahead of us, including coming to terms with centuries of trauma in North American Indian boarding schools, which we have reported on earlier. This week, we asked journalist and author Bill Tammeus to report on an important nationwide effort to open up these relationships with a small first step: land acknowledgments.

.

Learning to take the small first step of ‘Land Acknowledgment’

.

By BILL TAMMEUS

Contributing Columnist

In the midst of racial unrest around the nation last year, my Kansas City congregation, which began at the end of the Civil War as an anti-slavery church, started a renewed anti-racism effort.

As part of this, I was especially drawn to explore how to educate ourselves about—and respond to the needs of—Indigenous people in our area. The gaps in my knowledge about American Indian history and culture were and remain legion. (Most of what I knew about “Indians” came from living for two years as a boy in India, but that wasn’t much use for this.)

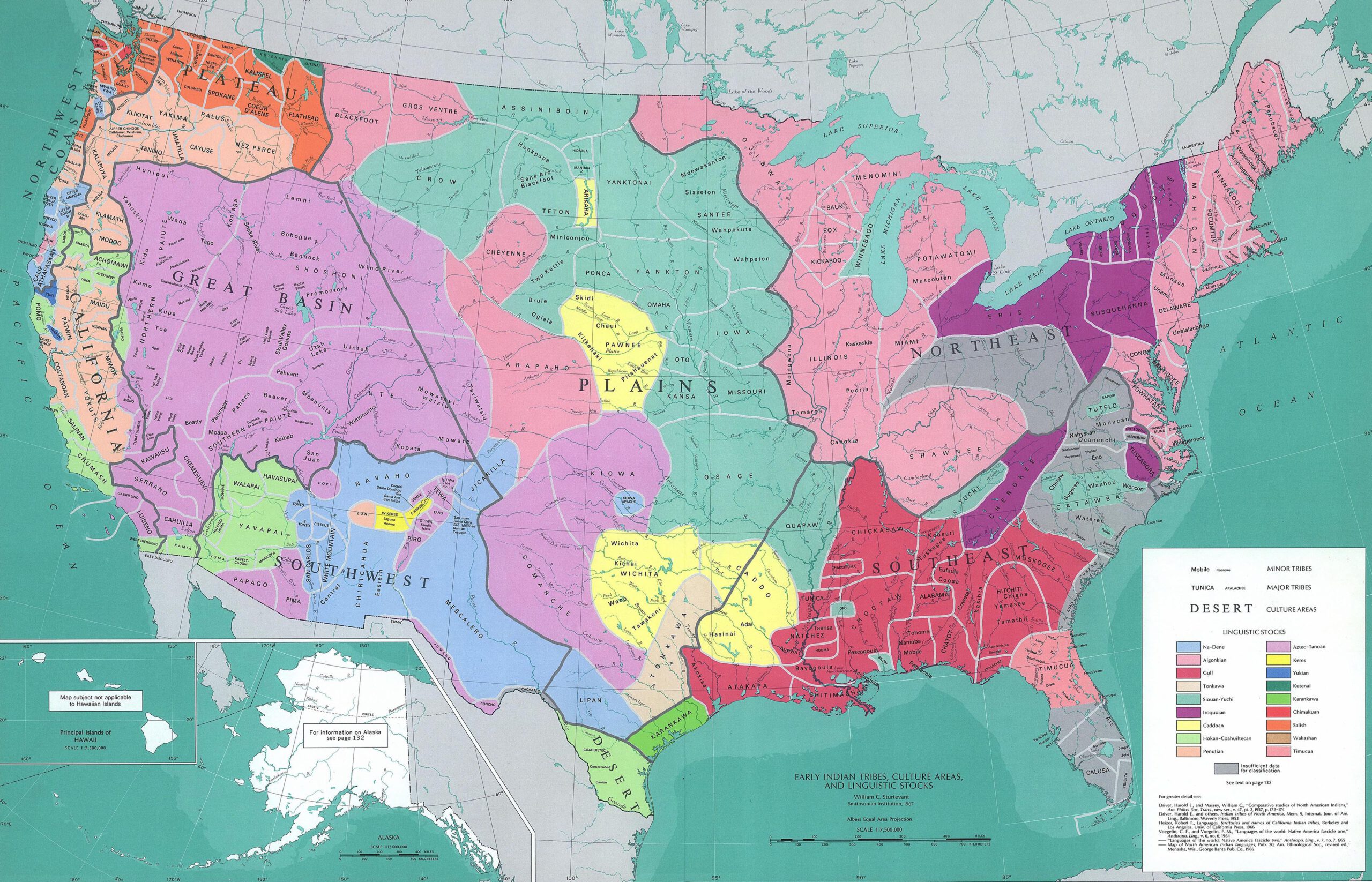

EARLY NATIVE AMERICAN LANGUAGE GROUPS: This U.S. government map is in the public domain. Remember that this is just one visual representation of lands that once were home to native peoples. Many smaller tribes were not included in this map. This map is also a snapshot from one era. Over many centuries, groups of people moved across the continent and these rough boundaries changed. As Bill Tammeus reports, the way to authentically explore land acknowledgment in your own part of North America begins with contacting Indian leaders in your region. (NOTE: Clicking on this map will display a much larger and more readable version. You also can right click on this map and save a copy on your phone or computer.)

So I began reading such books as An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, by Rosanne Dunbar-Ortiz; Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World, by Simon Winchester; How the Indians Lost their Land: Law and Power of the Frontier, by Stuart Banner, Diné: A History of the Navajos, by Peter Iverson, and Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants, by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Learning and Listening

Along the way we invited Native Americans to teach us about food sovereignty as well as land acknowledgements and other matters that were mostly unfamiliar to many of us. (Note: This link to “land acknowledgements” will take you to the Smithsonian’s informative website; a second “land acknowledgments” link below will take you to the Native Governance Center’s website.)

In that journey, we found that it was important to let the Indigenous people we were contacting know that we were there to learn—and not to assume we knew what they needed and wanted.

So, when we learned of the Kansas City Indian Center’s practice of providing food and other necessities to people in need, we asked if we could help. The result was a collection of more than 250 pandemic-era items, such as wipes and hand sanitizers. Then, when we learned of the organization’s hopes to build a new commercial kitchen to process Native-grown crops, we asked again if we could help. The result was that our members donated more than $15,000 toward the kitchen’s construction.

Let me repeat this point, because it is important: We don’t go to Indigenous people to tell them what they need and what we’ll do about it. We go to learn and listen. And, where appropriate, to walk with them.

So when I learned about land acknowledgements, the idea especially intrigued me. This practice provides a chance for the current (usually white) owners of particular parcels of land to recognize in public ways that the land they own—or the land on which, say, their church building sits—is considered ancestral tribal land by Indigenous people from whom it may have been stolen or taken via broken treaties.

‘A Very Small Gesture’

I used a land acknowledgement statement in September when I preached and led a discussion of my new book, Love, Loss and Endurance, at a church in Chicagoland. I told people that such acknowledgements are a very small gesture—but they’re not nothing.

And by “very small gesture,” I mean exactly that.

As Ed Smith, a staff member of the Kansas City Indian Center told me about land acknowledgements: “I don’t think much of them. If all they do is acknowledge that you’re on stolen land but aren’t going to do anything else after that, it wouldn’t be much different than me driving by after my grandpa stole your grandpa’s car—admitting that my grandpa stole it years ago and leaving with it anyway.”

Well, what “car” are we talking about?

The quick answer: The land that makes up the U.S. today.

As Banner writes in How the Indians Lost Their Land, “Between the early seventeenth century and the early twentieth century, almost all the land in the present-day United States was transferred from American Indians to non-Indians.”

True, but it’s more complicated than that. For one thing, his verb “transferred” makes it sound like it was a simple sale of land from Indians to whites. As Banner notes, however, “Indians had different conceptions of property than European settlers had. . .so they couldn’t have understood what the settlers (“settlers” refers mostly to European invaders) meant by a sale. The Indians were really conquered by force.”

But he acknowledges that even that’s an over-simplified version.

Banner again: “At most times, and in most places, the Indians were not exactly conquered, but they did not exactly choose to sell their land either. The truth was somewhere in the middle. . .Whites always acquired Indian land within a legal framework of their own construction. Law was always present, but so was power. The more powerful whites became relative to Indians, the more they were able to mold the legal system to produce outcomes in their favor—more sales, of larger tracts, at lower prices than would have existed had power relationships been more equal.”

That’s a lot to say in a simple land acknowledgement statement!

‘Architects of Removal’

And yet there’s more. As Winchester notes in his 2021 book, Land, “(W)estward was. . .the direction to which white men moved to fulfill their promised destiny. Westward to the ever-shifting frontier, with the Indians moved ahead and into the unknown, beyond their own Pales of Settlement, and to places where, in the white men’s eyes, they could do no harm except to their savage and miserable selves. There were many architects of the removal plan.”

Among those architects he mentions Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe and John Quincy Adams, “(b)ut then, and most notoriously, came the seventh president, Andrew Jackson, a Democrat who would have no further truck with an evidently recalcitrant aggregation of Indian feeling in the fertile settler country of the American southeast. He wanted all to go—particularly those acknowledged to be advanced, settled and self-governing, and condescendingly known as the Five Civilized Tribes. They were told. . .go head out. . .”

In a phone interview, Winchester described himself as uninspired by land acknowledgements, though he thought they had some small value. He called such acknowledgements “outwardly pointless but they get people thinking,” noting that acknowledgements began years ago in Australia and New Zealand.

Still, he said, “a lot of Native Americans are quite right to scoff at it. But in its defense, I think it means that some people are starting to consider the problem, which they’ve long glossed over and decided not to pay any attention to. I am hopeful that it will prompt a few people to consider what we’ve done to Native Americans.”

Indigenous People Still Live Among Us

So I plan to continue using land acknowledgement statements at appropriate times and my church will be using them to recognize the bloody history that has brought us to today and to acknowledge that Indigenous people are still here and have a future.

But if we don’t do more than that by, say, trying to respond in helpful ways to the needs of Indigenous people, such acknowledgements will barely be worth the paper on which they’re written.

.

Care to learn more?

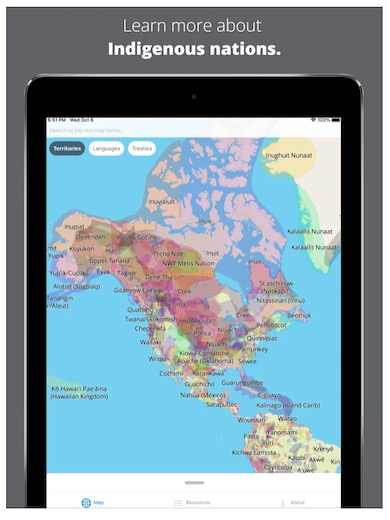

One way to determine which Indigenous peoples once occupied any particular area of the U.S., the Native Lands app is useful. Native Land Digital, which produces this app, is a Canadian not-for-profit organization, incorporated in December 2018. Native Land Digital is Indigenous-led, with an Indigenous Executive Director and Board of Directors who oversee and direct the organization. Numerous non-Indigenous people also contribute as members of the nonprofit’s Advisory Council.

One way to determine which Indigenous peoples once occupied any particular area of the U.S., the Native Lands app is useful. Native Land Digital, which produces this app, is a Canadian not-for-profit organization, incorporated in December 2018. Native Land Digital is Indigenous-led, with an Indigenous Executive Director and Board of Directors who oversee and direct the organization. Numerous non-Indigenous people also contribute as members of the nonprofit’s Advisory Council.

.

Bill Tammeus, a former award-winning columnist for The Kansas City Star, writes the “Faith Matters” blog for The Star’s website and columns for The Presbyterian Outlook and formerly for The National Catholic Reporter. His latest book is Love, Loss and Endurance: A 9/11 Story of Resilience and Hope in an Age of Anxiety. Email him at [email protected].

.