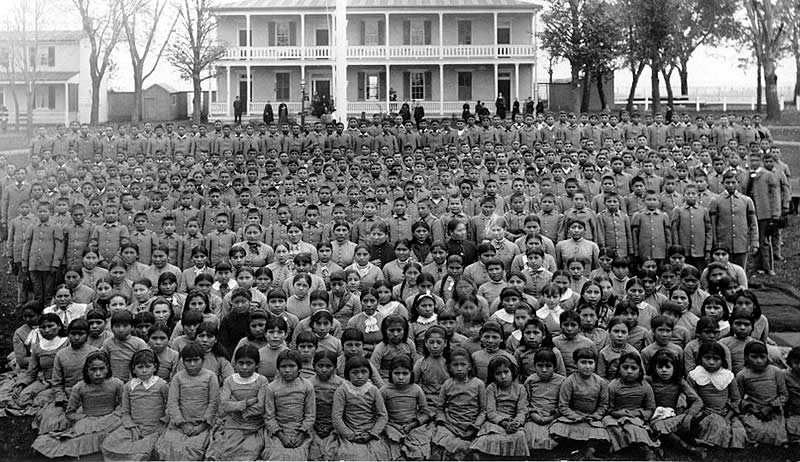

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the best known institution in this nationwide system of “schools” where children were forced to give up their Native languages, dress and customs. Author Warren Petoskey’s grandfather was among the children forced to attend Carlisle.

.

“Dedication: In honor of the victims and survivors of the Indian boarding schools, orphanages and foster care systems …”

First words in Warren Petoskey’s memoir Dancing My Dream“The Indian Boarding School story that Warren Petoskey shares with readers is all too familiar to Indians in the United States and Canada. The story, however, is an unfamiliar one to white America. It is a story that needs to be told. Virtually every Indian family was touched by the policy of assimilation that the boarding schools were designed to promote. “Kill the Indian, but save the child” was the desired outcome. Instead of assimilation, the boarding schools created a syndrome of intergenerational trauma that afects most Indians in America to this day.”

Anthropologist Kay McGowan in the Foreword to Dancing My Dream

.

UPDATES: On July 11, 2021, an alert reader suggested we also share a link to this National Public Radio report on July 11 that represents a fairly in-depth overview of the story to date. And, on July 4, 2021, we published this column by Madonna Thunder Hawk of the Lakota People’s Law Project.

.

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

The stories are true.

As horrifying as these stories seemed when they emerged into white American journalism over the years—stories of Indian children beaten to death or murdered in other ways over many years by a systematic government-sponsored repression of the Native population—the fact is: The stories are true.

We should have known better, but in the summer of 2021, the world is shocked to read about the discoveries of hundreds of children’s bodies buried near the sites of former Canadian Indian schools where Native children were held against their will.

- New York Times, June 24, 2021, In Canada, Another ‘Horrific’ Discovery of Indigenous Children’s Remains

- National Public Radio, June 24, 2021, Hundreds Of Unmarked Graves Found At Another Former School For Indigenous Children

- BBC News, June 24, 2021, Canada: 751 unmarked graves found at residential school

- For the latest news, simply visit Google-News and search for Native American boarding schools.

And the American chapter of this story is coming. Soon, all of us who have been following this story expect that we will begin reading such horrifying news reports from across the United States. A forensic process to search for mass graves near boarding schools in this country is only beginning.

- Washington Post, June 11, 2021, Opinion piece by U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, My grandparents were stolen from their families as children. We must learn about this history.

- USA Today, June 22, 2021, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to address legacy of Indigenous boarding schools.

- New York Times, June 23, 2021, U.S. to Search Former Native American Schools for Children’s Remains

Why Our Front Edge Team Cares So Much

One reason that the folks at ReadTheSpirit magazine and Front Edge Publishing feel so strongly about justice for the long-oppressed Native peoples across North America is that our co-founders, our Publisher John Hile and I (Editor David Crumm), have been advocates for these issues for many decades.

As early as the 1990s, I was the leading American wire-service reporter covering a tragically ill-conceived United Methodist attempt to take the traditional Native American Green Corn Ceremony, revise it as a Christian ritual and print it in a new edition of the denomination’s worldwide guide to worship. United Methodists thought this was one way to honor the many Indian Christians within the denomination. However, those church leaders had failed to widely consult with Native leaders. In fact, most Indian leaders remained deeply wounded by the denomination’s refusal to publicly apologize for a Methodist preacher, John Chivington, who led the Sand Creek Massacre of hundreds of men, women and children. As a result of that wire-service reporting on the United Methodist Green Corn controversy, the denomination eventually met with Native leaders, dropped their plans to Christianize the traditional ritual—and did formally apologize for Chivington and the church’s role in Sand Creek.

Why Indigenous Voices Are So Important:

‘Race, Public Memory and Intellectual Property’

Site of the Sand Creek Massacre as it looked in 2004, when the National Park Service was beginning to develop visitors’ resources near this rolling grassland in the prairie. Photograph by John Hile.

In 2004, working with John Hile as the photographer, I launched another wire-service project in the American West, a series of reports about deep wounds in American history that was called Anger in America during the week-long run of these stories.One extensive part of that series focused on Sand Creek, which the federal government was in the process of transforming into a protected National Park Service National Historic Site. The reporting we did that summer wound up being cited in a great deal of other writing about injustices toward Native Americans. Among those other writings was a 2013 dissertation by Susan Chase Hall, which she titled Something Terrible Happened Here: Memory and Battlefield Preservation in the Construction of Race, Place and Nation.

In her book-length dissertation, Hall wrote:

In Anger in America, Crumm explained that “America’s anger often is fueled by the movement of people, especially as outsiders move into settled communities. But the problem is more complex. After all, in America, who is truly a settler and who is an outsider?” In his reporting, David Crumm has introduced an essential question of race, public memory and intellectual property rights. At the beginning of the 21st Century, who had a right to weigh in on what happened at Sand Creek and why? Who had a right to tell the Sand Creek story? Who has a right to be angry about what happened at Sand Creek?

Please, Learn More about Boarding School Trauma from a Native American

This is why our publishing house, which was founded in 2007, almost immediately began developing a Native American memoir with Warren Petoskey, an Elder of the Waganakising Odawa and Minneconjou Lakotah Nations. He is a freelance writer, native artisan, traditional musician and dancer, ordained Christian minister and a lecturer who speaks frequently on the history of the nation’s infamous Indian boarding school system.

Warren talked at length about these issues in a 2009 ReadTheSpirit Cover Story. As part of that earlier “conversation with Warren Petoskey,” he said: “I think the greatest damage that was done was spiritual. As we lost our traditional languages, our elders will tell you that we lost something in the way that we pray. And there is an even larger spiritual wound here. This was more than a century of organized attempts by our government to destroy our spiritual validation as human beings.”

To learn even more, please order a copy of Warren’s book today from Amazon.

And—we’ve got more about Warren’s book in this week’s Front Edge Publishing column, including an inspiring excerpt from the book. Plus, in that Front Edge story, we’ve got an overview of our other important book produced with Native American journalists, 100 Questions, 500 Nations: A Guide to Native America.