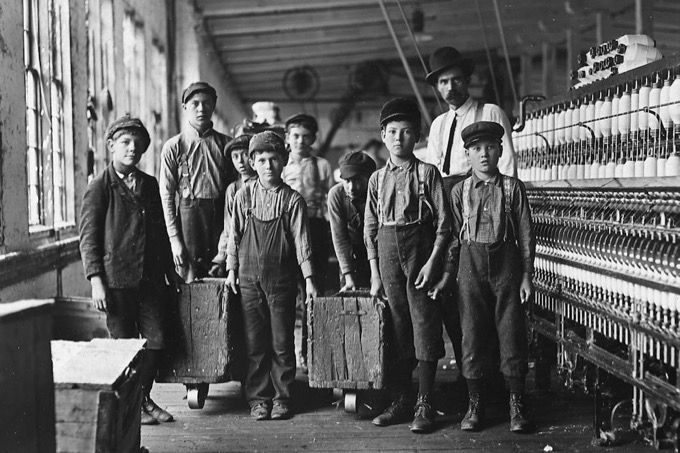

REMEMBERING THE IMPORTANCE OF THE LABOR MOVEMENT: Sociologist Lewis Hine took this photo in 1908, showing some of the doffers with their superintendent. A doffer tended the spindles on the machine, removing full ones and replacing them with empty spools; ten small boys and girls about this age would be employed in a force of 40 employees. Catawba Cotton Mill. Newton, N.C.

.

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 7: Even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, travel and small festive gatherings are expected nationwide—even though the bigger parades, fireworks shows and jam-packed picnic grounds at parks will be missed this year.

REMEMBER: CHECK LOCAL LISTINGS IN YOUR AREA

News reports about closings (and some local adaptations) have been trickling in from across the U.S. throughout August. Closer to Labor Day, check out resources like the PBS network listings and Amazon and Netflix streaming services for at-home streaming films and documentaries related to the observance.

The relentless spread of COVID-19 has changed plans in tiny towns and sprawling cities. Even in Texas, where public sentiment often has pushed back on pandemic limitations, the public parks around San Antonio will be closed throughout the entire weekend. Other Texas communities are expected to follow suit.

Similar news of park closings is popping up coast to coast. Some communities plan to continue fireworks shows, especially if the emphasis is on “drive in” attendance by families. Most fireworks shows are being cancelled. Yet another example from the West: Omaha cancelled not only Labor Day events but its entire schedule for the city’s upcoming Septemberfest. From the Midwest: In Duluth, city officials announced that their regular contractor for fireworks agreed to let the cash-strapped city cancel the fiery celebration with no cancellation cost, which softened the blow a bit for city residents.

Got extra time? Learn the history …

This year, in particular, educators, labor leaders and historians are urging Americans to use their extra time to look back at the history and relevance of labor in the lives of American workers.

Our opening photo, above, is one of many preserved by sociologist Lewis Hines. Consider creating your own Labor Day-themed media. You could share a message with friends on social media—or perhaps put together a discussion for your small group or class. Wikimedia Commons provides many of Hine’s classic images that you are free to use.)

Labor Day is the result of the long struggle for recognition of workers’ rights by the American labor movement. The first Labor Day celebration, observed in 1882 in New York City, attracted more than 10,000 workers who marched through the streets. Beyond recognizing the social and economic achievements of American workers, Labor Day makes us aware of the countless workers who have, together, contributed to the strength and prosperity of their country.

John Wesley drew the fury of many critics for preaching in public places, wherever crowds of working people and their families could gather to hear him.

LABOR AND FAITH

The value of human labor is echoed throughout the Abrahamic tradition, including stories and wisdom about the nature of labor in both the Bible and the Quran. Biblical passages ask God to “prosper the work of our hands” (Psalm 90), while the Quran refers to the morality of conducting oneself in the public square.

The Catholic church has been preaching on behalf of workers for more than a century. The landmark papal encyclical Rerum Novarum (“Of revolutionary change”) was published in 1891 and has been described as a primer on the rights of laborers who face abusive conditions in the workplace. This became one of the central themes of Pope John Paul II’s long pontificate. In 1981, he published his own lengthy encyclical, Laborem Exercens (“On human work”). Then, a decade later, John Paul returned to this milestone in Catholic teaching in Centisimus Annus (“Hundredth year”).

For 2019, the United Methodist Church published a nationwide appeal to church leaders to remember the central issues still faced by workers around the world. Titled “Labor Day Is Not Just a Day Off,” the text says in part:

Did you know The United Methodist Church has been a part of the labor movement throughout history and is committed to fairness and justice in the workplace? In the early 20th century the church was working to end child labor. And in the ’50s, during our country’s civil rights movement, we were fighting for fair wages and better working conditions. We were dedicated to fairness and justice in the workplace then, and we still are today.

When John Wesley founded the Methodist movement during the 18th century, there was no “worker movement” the way we’d understand it today. But Wesley preached to and cared for coal miners and other oppressed workers. He also opposed slavery. After Wesley died, his followers continued to work against workplace injustices in rapidly industrializing England, adopting the first Social Creed, in 1908, that dealt exclusively with labor practices.

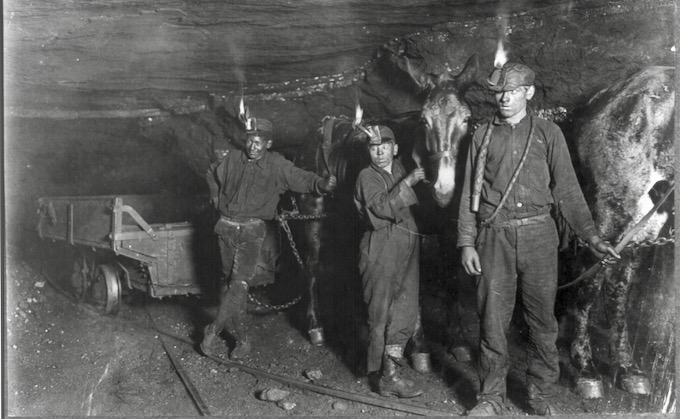

It may be hard to tell at first glance, but these miners also were child laborers documented by Lewis Hine in 1908.

FROM 12-HOUR DAYS AND DANGEROUS CONDITIONS TO UNIONS

At the end of the 19th century, many Americans had to work 12-hour days every day of the week to make a living. Child labor was at its height in mills, factories and mines, and young children earned only a portion of an adult’s wage. Dirty air, unsafe working conditions and low wages made labor in many cities a dangerous occupation. As working conditions worsened, workers came together and began forming labor unions: through unions, workers could have a voice by participating in strikes and rallies. Through unions, Americans fought against child labor and for the eight-hour workday.

Some labor demonstrations turned violent—such as the Haymarket Riot of 1886, which is remembered, to this day, in May 1 labor holidays around the world. Instead of a May holiday, however, American leaders preferred to remove “our” holiday from that tragedy by four months, in the civic calendar. Instead, American holiday planners encouraged street parades and public displays of the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations in each community—including cheerful festivities and recreation for workers and their families.

Oregon became the first state to declare Labor Day a holiday, in 1887, and by 1896, Labor Day was a national holiday.

Tell Us What You Think