EDITOR’S NOTE: Memory is a myserteous window that often opens unexpected vistas from our past. That’s what author and leadership coach Larry Buxton discovered when the leader of a writing class he was taking at Chautauqua this year asked participants to begin writing from the prompt of a single image. In Larry’s case it was a tree. Please enjoy Larry’s inspiring journey into his memories of family, love and loss. This story may prompt you to begin writing about some of your own family memories. So, please share this story with friends via social media or email. Who knows? You may discover a circle of friends reliving memories with you.

.

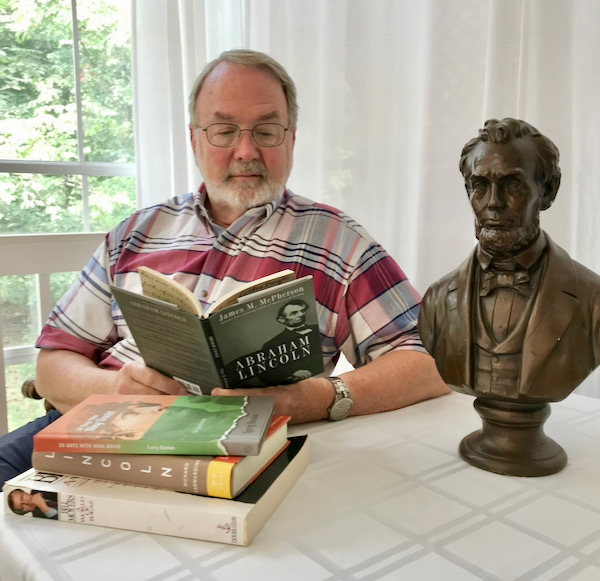

By LARRY BUXTON

Author of 30 Days with King David: On Leadership

In the shadows of the side yard of my house stood a single tall pine. From it hung, for some mysterious reason, a child’s delight—a swing. It was a simple swing, a thick board with two holes at each end and a bristly rope that soared up to the lowest sturdy branch. The length of the ropes made for an unusually long arc and high pitch.

That side yard was not only shady but also long and narrow. I guess the house hadn’t been centered exactly on the lot, because the yard on the other side was spacious and wide, open enough that Dad could stride across it, step easily through the bushes, and talk with our neighbor about, I don’t know, lawn mowers and grass seed.

But the narrow side had, as its only distinguishing feature, the pine tree with the empty swing. It rose past my younger brother Craig’s upstairs bedroom window, where he could see the knotted ropes securing the thick board below.

That swing remained a mystery to me all of my childhood. I don’t know who put it there or how. Maybe Dad had paid one of the construction workers to swing his crane over a few yards and attach the rope. Dad never mentioned it or asked about it. He never pushed me on the swing, nor my brothers either. While I swung there a few times, that strip of yard wasn’t an inviting place for a swarm of boys to play. So the swing stayed empty and unused for all of my young life.

Only Craig was privy to seeing it on a regular basis.

How was it, I wonder now, that I could spend a formative fourteen years oblivious to that silent presence outside the window? Even more perplexing, how was it I was equally oblivious to the drama of the silent presence inside the same window?

Craig spent hours in that room with the door closed. He hibernated there from stepping off the school bus to being called for dinner. When he opened the door, sometimes the cat would bolt out mewling and run down the stairs. After dinner, again behind the door, we’d hear muffled drums and fuzz-tone guitars, occasional thuds, once or twice a whiff of cigarette smoke.

I was barely a teenager when Craig’s schedule added weekly visits to “the doctor.” When my older brother and I asked what was going on, we learned a new word: “confidentiality.” We heard vague explanations like, “He helps Craig make better decisions.”

We’d ask Craig, who simply shot back, “I don’t want to talk about it.” So, like the silent pine and unused swing outside his window, he too remained a mystery.

The following year Craig was enrolled in a private school in Pennsylvania. “He can get better help there,” we were told, and “He’ll have teachers who can give him more attention.” Now his bedroom stayed open because no one was ever in it. This was the case for two years.

The summer I graduated high school, I took a camp job two hours away, and Craig returned home. He attended three local private schools in four years, never in dramatic trouble but repeatedly not invited back for the following year. We spoke only rarely and briefly.

I learned that while he was in his senior year of high school he’d been invited to an evangelical church. He liked it. He kept going, and a few weeks later he had a “conversion experience.” While we were all somewhat skeptical, over time there were fewer arguments at home, fewer locked doors, and higher marks at school. He got a part-time job and continued to attend his church. In September he went off to college.

Over the decades that ensued, Craig finished college and pinged from job to job—funeral home assistant, car salesman, a Time-Life operator who was standing by to take your call. He got into seminary, then got ordained, and bounced from one small church to another. He was good at only short-term relationships, so he became, perhaps inevitably, a hospice chaplain.

Whether I reached out frequently or sporadically, Craig always kept his distance. He lived alone, rarely answered his phone (but emailed torrents of jokes and comics), and held his daily activities close to his chest.

Late last winter Craig died unexpectedly of a heart attack. We planned for a small funeral, but when the day came, I was taken aback at the turnout. The church ran out of bulletins. The sanctuary was packed with people of different races and ages and economic conditions, some in their Sunday finest and some in work clothes. One after another, man or woman would stand to tell a story of Craig’s kindness or his generosity, a welcome prison visit or a bedside prayer.

One man who served as a health care aide to an elderly church member stood to say, “Every time Craig visited Miss Ellen, he always spoke to me—by name—like I was somebody important.”

For 90 minutes the church chuckled in recognition, elbowed its neighbors, and dabbed its eyes.

I left the church pondering the mystery of a brother I had known—and not known. How he spent his days, and how all these people came to know and love him, would forever remain in the shade for me. I was able to greet neighbors through the bushes much more easily, but he had an ability to walk in the narrower, even shadier, margins of life.

Unlike the swing, I doubt Craig ever soared high and free. Rather, the solitary pine outside his window modeled how he could send deep roots into God and thrive, and how, from an outstretched arm, he could extend a gift he could never enjoy, but always offer.

.

Care to read more?

Larry Buxton works as a consultant with a wide range of leaders. Click on this cover to visit his book’s Amazon page.

VISIT LARRY: You’ll find lots of inspiring and thought-provoking videos and columns at his website, simply LarryBuxton.com

ORDER HIS BOOK: 30 Days with King David: On Leadership is available on Amazon in Kindle, hardcover and paperback.