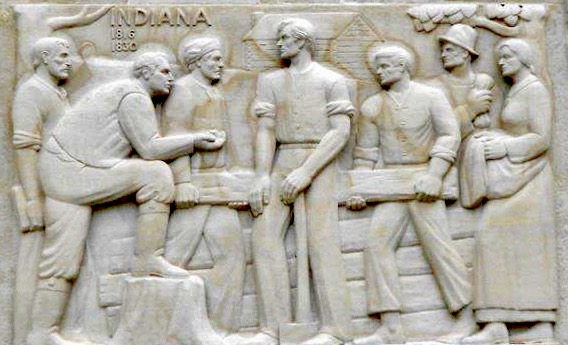

The stone relief symbolically depicting Lincoln’s boyhood in Indiana from the National Park Service center at Pigeon Creek, Indiana.

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

Abraham Lincoln

his hand and pen

he will be good but

god knows When

Do you remember that one from an earlier Quiet Fire episode? We are referring to a scrap of notebook paper from his few school days that has this little poem written out in his handwriting.

There are several things you can like about this. We can like that, as a bit of Lincoln’s spiritual DNA, he’s a pretty healthy minded kid. He capitalizes his name and leads off confidently with his big long name, Abraham Lincoln. He never liked just “Abe.” His Grandfather had been Captain Abraham Lincoln in the American Revolution.

We can enjoy that it is a poem. It may not be all that original, but it does rhyme: Lincoln with pen and when. And “god knows When” is a good money line. He does not capitalize “god” so we have a bit of rebel here as well, no?

And, the whole poem rotates around this one polar concept—Being Good. I will be good, but god knows when. So, being good is the be-all and end-all of the first poem by Lincoln. And it would be fair to say that when all is said and done being good was the be-all and end-all of his very life.

Walking Where Lincoln Walked

I had an experience once of walking down the hill on the Lincoln farm in Pigeon Creek, Indiana, and feeling that the very trees themselves held between the leaves fingered in all the branches the sheer goodness of Abraham Lincoln. My epiphany was that his goodness was so thick, so dense, so vital and long lasting that some of it was still lingering in the trees.

As if like a river fog it had lingered waiting for these very trees to grow up into it and hold it. I even felt that his goodness was like a trail of invisible light, like Wordsworth in his poem saying that “the Child is the Father of Man.” I felt that Lincoln had come into this world trailing clouds of glory and that his child really was the father of the man, at least of his kind of a man.

His relevance to us today is this: Being Good, while a life-long obsession with Lincoln, is for Americans, every once in a while, also our obsession. And these days it is.

So many things have gone wrong so fast and in such a big way that the idea is now very much in the air: Hey, let’s stop for a minute. What is life all about anyway, and what is it that we value. Truly value. What are our values and are we living them. Have they gotten away from us, or us from them?

Americans are pretty good at this kind of moral heart attack, and while we’re in the ICU we look at our values to how we want to live, if and when we come out.

What Were Lincoln’s Values?

At the top of Lincoln’s list, I believe, is what we might sum up as: Kindness. As Americans, that’s how we like to think of ourselves, isn’t it?

Americans, it turns out, hold “Kindness” as our No. 1 “character strength.” This finding is from a worldwide survey of over 50 nations, of whom none but the U.S. picked Kindness as No. 1.

Few presidents seem as kind, even kindly, as Abraham Lincoln. Among his notably kind acts, he forgave hundreds of deserting soldiers. Lincoln said in his First Inaugural Address, “We are not enemies. We must not be enemies.” He then appealed to the “better angels of our nature” so we would not become enemies. What shows the better angels of our nature more than our values?

10 Universal American Values

Not too long ago, I collaborated with University of Michigan sociologist Dr. Wayne Baker, comparing Lincoln’s true values with 10 almost universally held American values that kept turning up in Baker’s research. Remarkable, but true! Baker found that these 10 values are shared by the entire spectrum of Americans by a wide margin, over time.

Lincoln certainly shared these values, himself. Here’s that Baker-and-Lincoln list:

- Respect for Others. Lincoln’s single deepest value was his desire to earn the esteem of his fellow citizens, and he knew to do that he needed to be worthwhile to them. People felt this, his respect for them.

- Symbolic Patriotism. Most people now love him partly because he loved this county with mystic fervor. We see him as an icon for that love.

- Freedom. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master, this expresses my idea of democracy.…” That was just one of Lincoln’s affirmations of freedom. His view of slavery was that taking away the freedom of another human corrupted the person who did the taking.

- Security. He became the Commander in Chief over the largest use of force ever assembled in this country at that time. The war inflicted a total of 600,000+ casualties. He used force in an absolute way for the single purpose of re-establishing the authority of the national government, which he considered to be a sacred trust.

- Self-reliance and Individualism. Lincoln may have heard Ralph Waldo Emerson in a Chicago speech. He felt the deep call to find the force of nature that was in him and to fulfill what his partner William Herndon called “the little engine of his ambition.”

- Equal Opportunity. Five words, “All men are created equal,” described America’s common doorway to opportunity for Lincoln.

- Getting Ahead. Lincoln admitted his desire for the presidency. He was ambitious in advancing his career. He was the smartest person he knew. He worked long hours and hard ones. He was lucky often. When he saw a chance to merge his failing career with his moral passion to stop the spread of slavery, he became a national meteor.

- The Pursuit of Happiness. Lincoln made himself happy telling jokes, which he needed to relieve his melancholy. He deeply enjoyed the theater. As president, he learned to like opera. His chief pleasures were to read his Robert Burns and Lord Byron—and to read and recite Shakespeare. He had a frontier-man’s appetite for simple food, and he did not drink or smoke or lust after women. He did make money as a railroad lawyer in Illinois and had one of the better houses in Springfield. He was proud of his social achievement, but that was not what made him happy.

- Justice & Fairness. Kindness and mutual help was the way people survived and children grew up in the small settlements in Indiana when Lincoln was a boy. There were eight other families within a mile of his home in Pigeon Creek, and another six within two miles. Within four miles of his home there were 90 children under the age of seven and 48 between seven and seventeen. That adds up to a lot of people to enforce fairness and the Golden Rule.

- Critical Patriotism. In a speech to the New Jersey Legislature on his way to becoming president, Lincoln turned a crucial—and critical—phrase. He referred to America as “God’s almost chosen people.” That is what separates Lincoln from the glory gluttons of contemporary patriotism. He had a mystical awe for what self-government in a free land could mean for the human race. He was not ever in favor of the nativist American movement that wanted to slam the door on immigrants. Lincoln was poised to be critical of just about everything. He and Mark Twain would have been Mississippi riverboat soul mates joking with skeptical discontent in the service of a freer humanity.

We know from his life and words that his appeal to values failed in preventing the Civil War. Competing values themselves made the Civil War. Ironically, it was killer angels that made happen what our better angels failed to do. This was the tragedy of that failed conversation about values. Nevertheless it is by honor that we, too, like Lincoln can be lighted down to the latest generation.

.

.

Care to Read More in our Fourth of July 2023 series on Lincoln?

Whatever you choose to read next, you will find the following links to the other 2023 columns at the bottom of each page:

Lincoln scholar Duncan Newcomer’s introduction to this series includes a salute to Braver Angels, a nationwide nonprofit dedicated to de-polarizing American politics that is gathering from across the country for a major conference at Gettysburg this week.

Duncan also writes about: What were Lincoln’s hopes for our nation?

And, he explores: What were Lincoln’s core values?

Then, journalist and author Bill Tammeus writes about how Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address still calls us to reach out to one another.

Journalist and author Martin Davis asks: Are our battle-scarred American roads capable of carrying us toward unity?

Author and leadership coach Larry Buxton writes about: Growing up and growing wise with Abraham Lincoln

Columnist and editor Judith Pratt recalls: Hearing our Civil War stories shared generation to generation.

Attorney and community activist Mark Jacobs writes about: How Lincoln’s astonishing resilience and perseverance inspires me today

.

.

Want the book?

Want the book?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln