By HENRY BRINTON

Contributing Columnist

As we approach Election Day 2020, we are not seeing much respect across our political spectrum. This is a big concern to me, because respect is essential to a functioning community and nation.

Notice that I didn’t say “love.” I don’t expect love. It would be crazy for me to expect the supporters of Donald Trump to love Joe Biden, and the fans of Biden to love Trump. Love is a very private, personal, intimate emotion, one that really should be reserved for family members, friends and fellow members of a congregation.

But respect: That’s different. From my training in community organizing, I’ve learned that respect is a public emotion. I can respect someone with a different set of politics. A different education. A different religion. A different job. A different gender identity, race, or cultural background.

A generation ago, President Ronald Reagan and House Speaker Tip O’Neill respected each other. A Republican and a Democrat. Imagine that. The loss of such respect, among politicians and their supporters, is a big problem for us today. It affects our church, our community, our nation and our world.

Respect in the Bible

In his letter to the Philippians, the apostle Paul demands respect: “If anyone has reason to be confident,” he writes, “I have more: circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee; as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless” (3:4-6).

Paul was not only a good Jew, “a Hebrew born of Hebrews,” but he was a superstar of the Jewish faith: He was a zealous Pharisee and a blameless keeper of the law. He was a man of strong convictions, a person of integrity. But then he developed a new passion. He shifted his focus toward knowing Christ, gaining Christ, becoming like Christ, and loving Christ.

John Wesley’s Advice

So, what guidance does this give Christians in a polarized political environment? First, I believe we should do our best to respect people of different religious and political beliefs. We don’t have to agree with them, support them, or endorse their points of view, but we should show them respect.

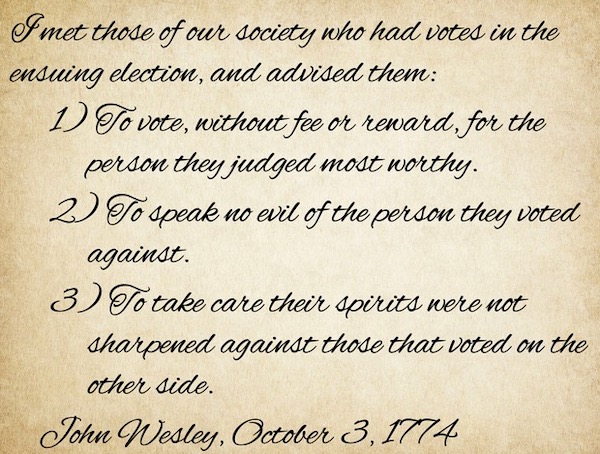

John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement around the world, offered some guidance to voters before an election in 1774. He said that, first, they should vote “for the person they judged most worthy.” Second, they should “speak no evil of the person they voted against.” And third, they should “take care their spirits were not sharpened against those that voted on the other side.”

That’s good advice. Vote for the person you judge most worthy. Speak no evil about the opposing candidate. And don’t sharpen your spirit against those that voted on the other side. In other words, show some respect.

Second, I think we should build on this respect as followers of Christ. Respect is good, but it is not enough. We should hold each other accountable, as well.

When We Go Wrong

Over the past generation, there has been a growing awareness of clergy sexual misconduct. Some of this has involved clergy who cross professional boundaries and have sex with church members, and some has involved clergy abusing children and teens. Whenever it happens, it is wrong. The reputation of clergy has taken a hit because of this misconduct. But this does not mean that all pastors are bad. Through appropriate discipline and better training, the chance of clergy sexual misconduct can be reduced.

In recent years, there also has been a growing awareness of police misconduct, especially towards Black men, women and young people. The reputation of police officers has taken a hit because of this misconduct. But this does not mean that all police officers are bad. I have a great deal of respect for law enforcement, and have been friends with a number of officers over the years. But we need to hold law enforcement accountable. Through discipline and training, the chance of police misconduct can be reduced.

I would say that the same holds true for our elected officials. We can respect them and also hold them accountable. To expect them to keep their word and act with integrity is not too high a standard. So write letters, make calls, send emails, and make sure you vote. Don’t speak evil of elected leaders, but do hold them accountable.

Ginsburg and Scalia at the opera.

Love at the Ginsburg Table

Finally, we need to develop personal relationships that move from respect to love. Remember, we should be more than respectable, according to Paul. Respect is good, but it is not enough. Those of us who are Christians should be truly loving, and should allow Jesus to change us.

Eugene Scalia is the U.S. secretary of labor and recently wrote a column about the friendship between his father, Antonin Scalia, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Both served until their deaths as Supreme Court justices. The two could not have been more different: Scalia was a Christian and Ginsburg was a Jew. Scalia was very conservative and Ginsburg was very liberal. But they, and their families, had a very close relationship. In fact, since the 1980s, they usually celebrated New Years together.

At these dinners, Justice Ginsburg’s husband Marty would prepare dinner. Sometimes he would prepare venison or boar that Justice Scalia had shot on a recent hunting trip. The families would drink champagne, listen to opera, and enjoy each other’s company. Scalia and Ginsburg were both New Yorkers and “they liked a lot of the same things,” says Eugene Scalia: “the law, teaching, travel, music and a meal with family and friends.”

They respected each other, and, even more importantly, they loved each other. And this love extended to their spouses. Marty Ginsburg had a “powerful love and dedication to his wife,” says Eugene Scalia. “He was a cherished friend for my mother.”

But this respect and love did not mean that the two justices agreed with each other. Ginsburg was a “pioneering advocate for women’s rights.” Scalia was “a critic of activist courts.” Ginsburg dismissed one of his arguments as “outlandish.” He said that one of her opinions was “politics smuggled into law.”

But they never condemned or ostracized each other. They learned from each other and knew that their debates were part of what makes our democracy great.

Christian Hospitality

In my novel City of Peace, an immigrant couple named Sofia and Youssef Ayad, Coptic Christians from Egypt, invite a Methodist pastor named Harley Camden over for dinner in the Town of Occoquan, Virginia. Harley had suffered the loss of his wife and daughter in a European terrorist attack.

“This food is delicious,” says Harley to Sofia. “Thank you very much. It all seems very healthy.”

“Food is important to us,” Sofia says. “Think of the many times that Jesus sat down to eat with people—even tax collectors and sinners. Christian hospitality is very important to Youssef and me.”

“I do appreciate it,” Harley adds. “Think of how much better the world would be if people actually sat down and ate with each other.”

“No doubt about it,” agrees Youssef. “The Bayatis have become some of our closest friends here in Occoquan, largely because we have shared so many meals. Back in Egypt, Christians and Muslims are getting together less and less, which has caused the animosity and violence to increase. Did you hear about the attack last December in Cairo?”

“No, I missed that,” admits Harley.

“A suicide bomber attacked St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral. More than two dozen worshipers were killed, including a ten-year-old girl.”

“It was horrible,” Sofia says, shaking her head. “The worst attack on Copts in years. The Islamic State claimed responsibility.”

“How did the Copts respond?” asks Harley.

“With increased security, of course,” says Youssef. “But also with prayer—prayers for the victims, and for their attackers.”

Harley is impressed that the Coptic community could respond with prayer for such evildoers. Thinking back over the past year, he hadn’t said a single prayer for the terrorists who killed his wife and daughter. And yet he knows that Jesus commanded his followers to pray for the people who persecuted them.

Yes, we live in a world of liberals and conservatives, supporters of Donald Trump and fans of Joe Biden. There is much that divides us in our fractured and polarized society. But good things happen when we find a way to respect each other and, even better, experience some love—as the Scalias and Ginsburgs did—in shared meals.

Truly, the world would be a better place if people actually sat down and ate with each other.

.

.

Care to learn more?

You’ll enjoy our March cover story about Henry and his new novel.

.

.

More about Henry

HENRY G. BRINTON is pastor of Fairfax Presbyterian Church in Virginia, and has written on religion and culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today, and Huffington Post.

A frequent speaker at workshops and conferences, he is the author or co-author of books including The Welcoming Congregation: Roots and Fruits of Christian Hospitality.—and a new cozy mystery called City of Peace.

Married with two adult children, he enjoys boating on the Potomac River and competing in endurance sports such as marathons.

Thanks for the notion of a “public emotion.”

The examples of clergy misconduct & police misconduct was eye opening for me. And I didn’t know about the meals between the Justices. Wonderful. Food and song.

Silent labyrinth walks can bond people too, and there are many around D.C..

You’ve made me want to eat with the Other!

Thank you, Duncan. May God bless your table fellowship (when public health allows!)