.

Millions of us still to turn to Luke’s masterpiece

.

By MARTIN DAVIS

Contributing Columnist

Fifty-five years ago, the CBS network broadcast this scene across North America: During a problem-plagued Christmas pageant, Charlie Brown shouted in exasperation, “Isn’t there anyone who knows what Christmas is all about!?!”

That’s when thumb-sucking, blanket-clutching Linus calmly replied, “Sure, Charlie Brown. I can tell you what Christmas is all about.”

Linus then moved to center stage, asking “Lights, please?”

With a spotlight illuminating him, Linus delivered what—at the time the cartoon was first broadcast—was considered a controversial passage direct from the Gospel of Luke, beginning with, “And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in their field keeping watch over their flocks by night.”

That Charles Schulz holiday TV special, sponsored by CBS and Coca-Cola, almost never saw the light of television. Network officials didn’t like the jazz music, the lack of a standard laugh track, the choice of real children to record the voices—and they especially didn’t like Linus’s recitation from Luke. Today, it’s hard to imagine why they were worried. At the time, more than 90 percent of Americans identified as Christians, but CBS network officials were afraid of making prime time “too religious.” In the end, they reluctantly broadcast the half-hour cartoon only because they already had paid for its production—telling Schultz bluntly that it would never be seen again.

Today, of course, A Charlie Brown Christmas is recognized as an innovative masterpiece. That’s despite the fact that America now is more secular than in the ’60s. An ever-growing number of Americans—it’s now about 1 in 4 of us—say they have no religious affiliation. My own occasional columns in ReadTheSpirit explore the spiritual lives of those of us who answer pollsters’ questions about our religious affiliation with: “None.”

So, where can all of us—including the millions of Nones—find meaning in this global celebration of Christmas?

This year for Christmas, I turned to a like-minded friend Everett Dagué to talk about Charlie Brown’s question 55 years ago. Like me, Everett is a None. But, as I soon learned in our interview, Everett was struck by Linus’s recitation in that TV special. That was the first time Everett can recall hearing the entire Nativity text from Luke.

I reached out to Everett because I was aware of a distinctive December tradition he has established that now reaches around the world. Everett spends a couple of weeks in early December on Facebook forgoing his usual posts highlighting dinosaurs, cats, military history and cleverly sarcastic political insights. Instead, he devotes a series of thought-provoking posts to re-telling the story of Jesus’ birth as recorded n the Gospel of Luke.

In fact, this year, he invited a couple of wise friends to collaborate in his series of Luke posts. (Care to see some samples of what Everett and his collaborators wrote? You’ll find three sample posts here.)

The Wisdom Everett Dagué Finds in Luke

Let me introduce our interview by telling you a little more about my friend Everett.

He doesn’t consider himself a Christian, and he doesn’t much care for the study of theology. He’s also progressive, although he’s no stereotypical bleeding heart. Everett served in Germany in the Cold War as a 19D Calvary Scout with the US Army. Today, he serves as Command Historian at the US Army NCO Leadership Center of Excellence and United States Army Sergeants-Major Academy and seems happiest when he’s on the firing range with a machine gun set on fully automatic.

He’s certainly not the guy you would expect to be presenting his own Nativity Pageant online every year!

So why this obsession with the birth of Jesus as described by Luke? The answers are as simple, and as complex, as the ways that Everett’s re-telling of this story has evolved. From a straight re-posting of the story over a period of days when he first began what has become an annual tradition—to re-posts with accompanying art or music. This year, he invited friends to help him ruminate on the meaning of the story for them.

Clearly, he has tapped into something. His re-posting of the story has become as much a tradition in many people’s homes as putting up the tree and singing carols. His effort has even gotten a person as devoutly non-religious as me to look forward to this annual series. I’ve known Everett since our days together in graduate school. So when Everett began this year’s retelling of the story, I sat down with him and talked about his journey over the past decade.

MARTIN: What motivated you to start this annual tradition of retelling the story of Jesus’ birth?

EVERETT: When I started this project, I was teaching at a small, private university in Kansas. The academic calendar is set up so that one has the time to really appreciate the stretch of holidays that begin with Thanksgiving and culminate with New Years. It always seemed to me that this holiday period was bookended appropriately. You begin by giving thanks for the year that you just had, and you end filled with anticipation for the year ahead. That all made sense. And it was all done in ways that celebrated our friends and families in ways that made us appreciate the moment we were in.

Christmas, however, was not this way. It finally dawned on me that we were approaching the holiday completely backwards. It wasn’t about the moment, or the people. It had become all about the stuff. I began writing the story of Jesus’ birth as a way to begin to turn the ship.

MARTIN: There are many people who would agree with you that Christmas has become too much about the stuff. Many of us would like to put the focus back on the spiritual. Is that what you’re trying to do?

EVERETT: Not at all. Just like you can over-materialize the holiday, you can over-religious it, too.

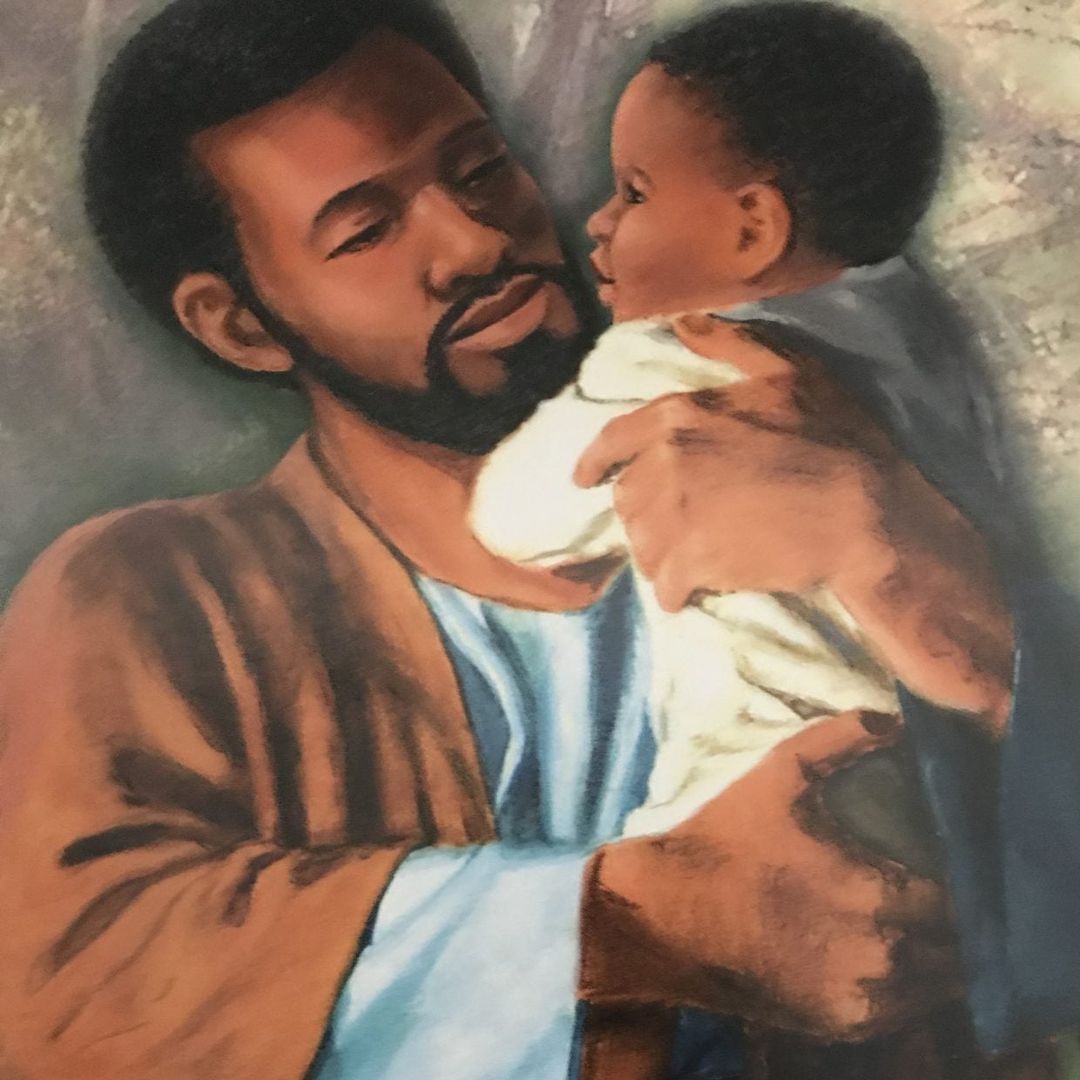

I enjoy retelling Luke’s story of the birth because it doesn’t depend on miracles, like Matthew and Mark do. It isn’t consumed with who Jesus is, like John is. It’s focused on the very human characters in the story. It gives us a window into the moments when Mary and Joseph and the shepherds experienced it all.

Being in that moment, embracing that humanity is what matters. I often think back to something we did growing up. Each year our family would draw names, and we had to take the name that we selected and write them a letter explaining what that person meant to us. That was placed in their stocking. This simple exercise allowed us to celebrate the people in our lives. To live in that moment.

MARTIN: You say that Luke doesn’t focus on miracles, but Chapter 1 is all about Mary’s conception, and the conception of John the Baptist. Both miraculous in their own ways.

EVERETT: Luke uses the miracles like virgin birth, but he does not rely on them to get his point across. For example, one of the most powerful images in Luke 1 is when Mary and Elizabeth meet, and Elisabeth is overcome with joy at seeing Mary, and she knows that Mary is pregnant. Elizabeth’s baby “leaps in the womb.” At that moment Elizabeth knows nothing about virgin births or angels or anything. All she knows is, her cousin is there with her and she is overjoyed. It’s a detail you wouldn’t find in the other Gospels.

Moreover, Chapter 2, the chapter that I focus on each year, focuses on the humanity of the story. And that’s why I picked it. I wanted to increase the awareness that there are more than two ways to read this story. The church would have you believe either you read this as the story of Jesus the savior, or you read this as a story of Jesus who was just a good person.

What both those approaches miss is the wonderful story of a birth. We can meet and understand Joseph the father. Mary the mother. Jesus the baby. Luke is the guy.

I’m not asking people to ignore the religious aspect. However, if all you’re seeing is the birth of the savior, you’re missing a lot there. No one knows he’s going to be the savior. Looking at what these people are doing, they’re doing it because there’s something good in them, and good in us, too. And that’s what Christmas is all about. That’s the world that we live in.

MARTIN: So are you saying that there is no miracle element to the story?

EVERETT: Not exactly. There is miracle. But it’s the miracle of the every day. You can be a Mary, unmarried and afraid, yet moving boldly forward with Joseph in spite of the insults and indignities the society heaped on her. You can be a Joseph. Joseph could have picked up and walked away and no one would have blamed him. But that’s not what Joseph does. The shepherds would have had no trouble just staying there with their sheep. But they don’t do that. Why do they do what they do?

When we think about the way we can make the world a better place, this is the story that tells you how to do that. By retelling the very human side of this story, I wanted to add an element that has been lost in this season. I get the centrality of Jesus, but for right now, for today, this is what this is about.

MARTIN: Your degree is in history. Is there a connection between the way you approach history, and the way you approach this story?

EVERETT: To be sure. One of the things I got in spades from Owen Connelly, the late, great Napoleonic scholar at the University of South Carolina, is that you read what’s there, not what you want it to mean or say. You have to learn to read a text for what it means. Not for what you want it to mean.

This doesn’t mean that you simply accept the words on the page blindly. You do your homework. You learn as much as you can about the writer and the period something was written in. But at the end of the day, you’ve got to take the text for what it is. That’s what I’m trying to regain in telling this story.

MARTIN: Your wife did her graduate work in literature. And you yourself are quite the fan of literature. I know from our years together, for example, that Moby Dick is a very important book for you. How has your approach to literature shaped the way you approach this story?

EVERETT: I’ve probably read Moby Dick 15 times, and every time that I read it I come away from it with a totally different understanding. This is what great literature does: Each stage of life that you read it brings new understanding and insights. So, let’s look at Moby Dick, since you’ve raised it. The last time I read it, I saw something I’d never really seen before. The Great Whale really represents God, and what drives Ahab’s fury is his inability to control God.

When I sit down and read Luke, I keep coming back to Joseph. I’m a guy, a husband, a father. I get him and understand him in ways I couldn’t understand Mary. When I think about what I should be like as a husband and a father, I find it in him. He doesn’t deal in anger. That’s what I’m seeing now. When I first encountered the story through hearing Linus recite it in the Peanuts Christmas special, I encountered it in a totally different way. This is the way you want your parents to be, your family to be. As you change, the meaning changes as well.

MARTIN: What’s been the biggest change in you in the years doing this?

EVERETT: There are a lot of things, but let me talk about one: I’ve learned how to be a parent from this annual reading. The birth of a baby is the beginning of something. You never quite lose the awe of that experience. And this is the nice thing about this story. But I’ve also learned a lot about how to accept my kids and my family as they are, and still grow to become who you need to be. It’s critical, however, as you grow to never forget that awe of experiencing the birth of a baby.

Then, if I might go for just a moment to a darker story that illuminates what I mean. When I was on faculty at Benedictine College, we had a Discovery Day where kids could work on any individual project they wanted. I had one student who wanted to put Joseph Mengele—the Nazi doctor notorious for the inhumane experiments he conducted on Jews—on trial. So we did. In the course of the trial, we had a “witness” (someone from the era whose memory was recorded in the record) who described a Nazi guard who kicked a baby just when it was born, killing it. The baby and the mother had just arrived on a train to Auschwitz.

The reason I do this reading every year, to remember the pure beauty of the birth of a child, is to counter that.

I have come to believe that you can change things within yourself and within the world itself by making people more aware of the miracle that is your kids. This story of birth is how we keep sight of that, by reminding people every year of the simple mystery and beauty of birth.

We have concentration camps right now in the United States along the border where the US government is doing unspeakable things to innocent mothers and children. Maybe what we need to do is be a little more aware that these are miraculous beings.

MARTIN: This year you are doing the story very differently. This year, you have collaborators. Why are you doing this?

EVERETT: I always try to do it differently. The first year I just posted the story. Then I began experimenting with art. I still have much to say, much to explore in this story. But I’m sure that people get a little tired of just me. So I’ve asked people who are good writers, but come from very different backgrounds, to help me write the entries this year.

It’s one more experiment in keeping the power of this story alive.

Want to Hear Linus’s Version?

You should see a YouTube video screen, below, where you can watch the now-famous clip of Linus from 55 years ago. If a video screen does not appear in your browser, you also can watch the clip directly on the YouTube website. (In some versions, you might have to briefly see a short advertisement.)

.

ReadTheSpirit Editor David Crumm contributed to this story.

.

.

Care to read more?

Or, hear more?

FIRST, you may want to read more from Everett and his friends. Because Facebook is such a fleeting medium, anyone trying to find the reflections on Luke’s Nativity story by Everett Dagué and his friends will have to search through lots of other posts before finding the Luke stories. So—with full credit and thanks to writers Everett, Rebecca Marie and James Lewis—we are presenting three sample posts from their December 2020 series.

ARE YOU INTRIGUED by this column from Martin Davis? You will also enjoy his book: 30 Days With America’s High School Coaches.

Martin Davis is a journalist living in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he is the Opinion Page editor of The Free Lance-Star in his hometown of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

,

,

Man! That’s the best Christmas Story version I have experienced in a long, long time, and I’ve been experiencing the Christmas Story in church for, maybe, seven decades, including me on the preaching side.

Rev. Dr. Duncan Newcomer