Donna Rockwell and her mother Elen Schwartz shared a special bond. Both petite in size, one reflected and one still reflects a big heart and positive influence on others.

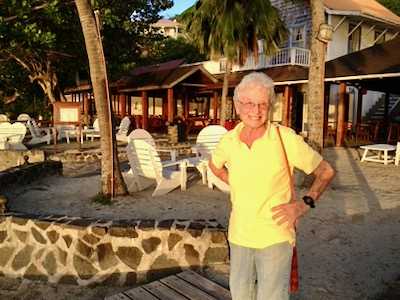

Elen died recently on the island of Barbados. She lived in the Caribbean for nearly 50 years, most on the tiny Grenadine island of Bequia. Neighbors regarded her as a kind of informal queen of the island until age 84. She was friend to the Prime Minister and taxi drivers alike.

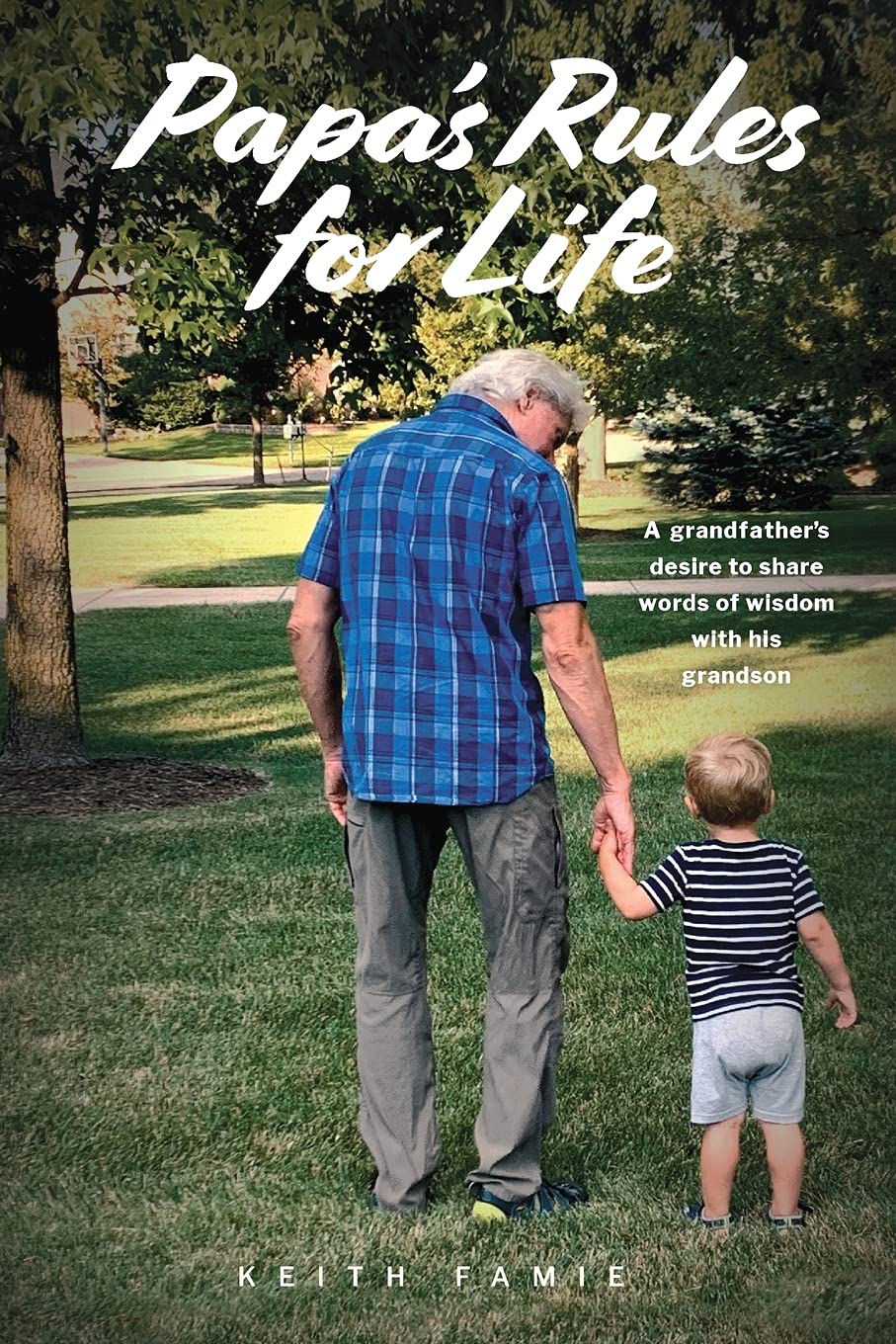

Though I missed the joy of meeting her Elen, Donna’s been writing a memoir about her vivacious mother.

“Mom was like a comet,” Donna says. “The life of any party.” Donna, a psychologist, “felt privileged to know my mom and to happily pour her scotch.”

Elen grew up in Weehawken, NJ, attended NYC’s prestigious professional school to become a ballet dancer and trained with famed choreographer George Balanchine. Her career was short-lived, Elen said, because her “bosoms got too big for ballet,” and she was forced to quit.

Elen didn’t quit at much. She was a go-getter from the get go. At Finch College in Manhattan, she wanted to become class president. She succeeded by studying a school yearbook, memorizing every student’s face and greeting each by name in the hallways. Later, she became president of the sisterhood of her synagogue in New Jersey and organized a cookbook of members’ favorite family recipes. She applied the same energy to motherhood. She was a den mother for her son’s Cub Scout troop and stayed up late adding tiny improvements to every boy’s craft project.

After leading a relatively conventional upper-middle-class life, Elen changed direction.

At a time when divorce was deemd a Shonda (Yiddish for shame), Elen divorced her first husband, Donna’s biological father. Donna was 11; brother Josh, 10; sister Leah, 6. Elen met and married Ray Schwartz, a New Jersey commercial real estate broker with two grown sons. Ray’s lifelong dream was to live in the islands and sail. After Elen and Ray married in summer, 1971, the couple and Elen’s three kids moved to Barbados and rented a house. Donna recalls, “It was a totally new environment, with British schools and uniforms, standing when teachers entered the classroom, having to wear a wide brimmed straw hat to and from school.”

The family bought a sailboat. On vacations, they sailed through the Grenadines.

“We slept on beaches in Mustique, picked vegetables in Canouan, saw amazing fish and coral off the coast of Grenada,” Donna says. Sadly, their idyll ended when, at 52, Ray contracted lung cancer. Elen went to the US to be with her husband for treatment. “She stayed for three months, cuddling with Ray in his bed until he died.” Back in Barbados, Donna, then 16, took charge of her siblings, preparing meals and getting them off to school.

”Mom was so stoic,” Donna says. “She refused to be sad. As she put it, ‘Most people never get to experience true love in life. I did.’”

When New Jersey friends encouraged Elen to move back to the states, Elen declined, saying, “Barbados is our home now.” The family had moved there when Donna was 14. Though resistant at first, Donna says, “I eventually realized we’d landed in paradise. From then on, my life was all about sunrises and sunsets and an expansive view of the sea. On an island, you’re forced to be present. You learn to synchronize to the rhythms of the planet.”

Elen threw “lavish, joyful parties” at their house. Among her many friends were Tony and Jeffrey, a gay couple who lived down the street. Jeffrey’s family were stationers to the queen of England. Donna deems Elen’s friends “as fascinating as she was.” Donna came to appreciate “a verve deep within West Indian culture.” She says her mom reflected that verve. “She was as spicy as the local hot sauce.”

When Elen’s youngest child, Leah, returned to the US for college, Elen moved to Bequia with her new boyfriend, Peter. Nine years younger, Peter was a German who’d sailed on his own from Hamburg to Barbados. Elen and Peter moved onto her boat and sailed together for ten years “until things got complicated.” Peter wanted children; Elen didn’t. He met a woman who did.

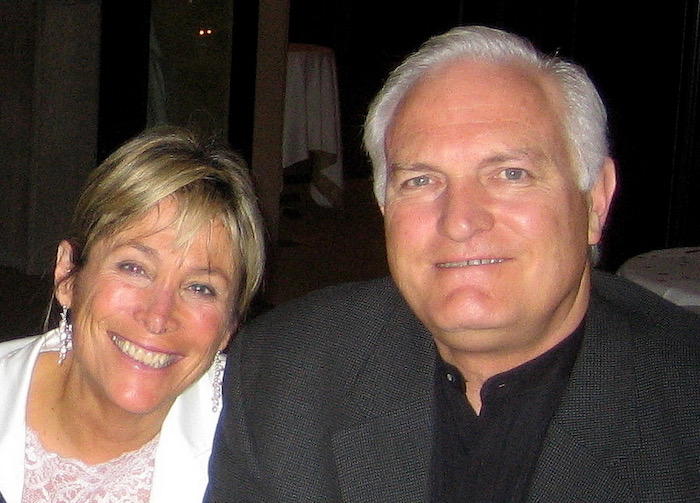

Meanwhile, Donna had married Bernie Smilovitz, Detroit’s WDIV sportscaster of 36 years.

Elen continued to live on her sailboat in Bequia’s Port Elizabeth Harbor. One sunny day, Peter, an alcoholic, left a photo of Elen in her mailbox with a note, “Thanks for all the memories.” Later that week, after sailing to Venezuela, Peter hung himself from the mast of his sailboat.

“Lots of happy memories and lots of drama,” Donna says.

Donna went on to earn a masters degree in journalism from American University in Washington, D.C. She visited her mom often. Those visits “were like arriving in Shangri la.” She’d fly to St. Vincent and take a two hour ride on the local schooner, Friendship Rose, to Bequia. Elen would be waiting at the dock, wearing a big straw hat. Elen enjoyed living among the European boating set, catching fresh fish in a cage hung over the side of her boat. She was beloved by the local islanders.

“In Bequia,” Elen said, “I’m the Belle of the Bay.”

When grandchildren visited, they’d walk through the center of town. Shop owners would shout, “Miss Elen! You’ve got the Grands!”

Meetings on Skype at 5pm became a daily ritual. Elen and Donna tag teamed each other’s jokes. But some days, Donna says, “even in paradise my mother expressed worries. Susan Jeffers’ Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway became her personal bible.”

In later years, Elen moved off the boat and became the overseer of a beautiful guest house. She’d walk upstairs, join guests for cocktails and regale them with stories of the islands or of the many books she read. Return guests said they’d come back just for Elen’s stories. Elen helped start Bequia’s Sunshine School for Children with Special Needs and remained active on its board.

A stroke in her early 80s slowed Elen down. She had smoked most of her life, refusing to quit because she “liked the effect.” In discussing a possible move to Michigan, Elen’s doctor warned Donna, “You mother’s been tropicalized. She won’t survive up north.”

Four years later, after a second stroke at age 84, Elen was flown to Barbados. She passed away peacefully in a nursing home. Tropical breezes wafted through the room, and she was surrounded by her three children. The week before, a little bird landed on her windowsill and stayed. Elen decided it was Ray.

On what would have been Elen’s 85th birthday, Donna and her siblings returned to Bequia. From a small skiff on a glittering morning, Elen’s children scattered her ashes in the ocean. On Becqui there’s a gourmet pizza restaurant, Mac & Judy’s, which Elen frequented. Even if she wasn’t dining there on any given day, she’d stick her head into the kitchen and call to the staff, “Hello, girls.”

After the funeral, Donna peeked into Mac & Judy’s kitchen and called, “Hello, girls.” When the staff heard Elen was back with them, at final rest in the sea, Donna says, “They were all sobbing.”

Donna says, “My mother was so affirming. If I hesitated about a decision, she quoted Shirley Temple’s mom. “Don’t wait. Do it now. Sparkle, Shirley.”

And Donna did.

(Check out next week’s column to see how Donna sparkles.)