Three years ago, I wrote a column on a big-hearted Sarasota lady with a dream. (“Graci McGillicuddy envisions kinder, gentler foster care”) A former teacher, Graci was dismayed by child abuse cases occurring in Florida. She dreamt of creating a better approach to foster care. She and husband Dennis have made that dream come true with the All-Star Children’s Foundation. To see for myself, I visited the campus. What Graci and Dennis have accomplished is remarkable.

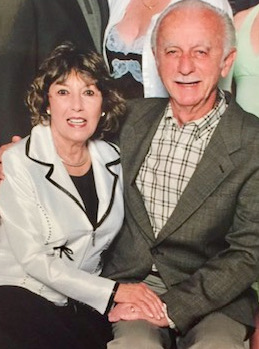

Graci McGillicuddy is in the center with a scarf. Left of her is Steve; right of her is her husband Dennis. Around them are some of the center’s staff members.

According to its website, All-Star “provides children victimized by abuse with a very special place—a place designed to soothe, empower and inspire.” All-Star lives up to its promise. Children receive “trauma-informed” treatment in a 5-acre site ringed by bright and stylish residences (designed by Graci) and a club house.

The McGillicuddys found four dedicated professionals to oversee All-Star. One is multi-talented Chief Development Officer Stephen Fancher. Steve’s a pianist trained at Trinity College of Music, SUNY Purchase, with a masters in piano performance, and a conductor. At All-Star, he also conducts fun and games. During my visit, he taught residents aged 3-20 to play ukuleles and mesmerized them with piano refrains from Beethoven and the Beatles.

Two good friends, Jackie Blanchard and Phyllis Keyser, both former educators, joined me on my visit to All-Star. Within five minutes of meeting Steve, Jackie murmured, “Little does he know he’s your next column.” Right she was.

From central Connecticut, Steve graduated from the U. of Conn., attended renowned Trinity College of Music in London and earned a masters in piano performance from SUNY Purchase, NY. He became certified and taught music in elementary school. His first daughter was born in 2010. At the time, he was a full time conductor and music educator in the Tri-State area working in Stamford, CT, and Chappaqua, NY.

Realizing his job had led to his missing the first 2 and ½ months of his daughter’s life, Steve decided to change directions. He studied for and received a stockbroker’s license and started a financial services business with his brother-in-law. In September, 2012, he moved to Sarasota. He joined Merrill Lynch as a financial advisor—a position he held for 4½ years.

“I wasn’t satisfied by the financial services industry,” he says. “I wasn’t committed at a deep level.” He decided to combine his business and musical backgrounds and seek a position in arts administration. A mutual friend (past Laurel Oak resident), Andrea Bilan, was then in development with JFCS. The agency needed a major gifts officer. Steve took the position.

18 months later he toured All-Star. He decided, “this is where I want to be.”

Musical talent often runs in families. My grandmother played the piano well. My sister Anne inherited her ability and still takes lessons. Plus she can sing. Sadly, my destiny included neither strength. After five childhood years of tortuous piano lessons, my repertoire consists of Chopsticks. And no one aside from yours truly appreciates my 5-note singing range.

Steve’s dad Richard, a sales rep for aeronautical engine company Pratt & Whitney, played the organ at Christ Episcopal Church in Middle Haddam, Conn. and sang with the New England Chamber Choir. Steve’s brother, a supermarket manager, is a self-taught guitarist who plays with top local bands.

Steve says, “I didn’t realize not every family could sing Happy Birthday in 4-part harmony. I had as much musical education as possible. My brother can’t read music past a basic level but he can play anything. That’s always annoyed me.

“Piano’s a big part of who I am. I see myself as a teacher. I love conducting and teaching singers and players how to make music together.” Steve says he “tried” to take some time off from the piano when he was in financial services. “I couldn’t do it.” He joined the Sarasota Key Chorale as a tenor. The Chorale is a chorus of about 100 musicians who sing with the orchestra. Music director Joseph Caulkins is one of Steve’s best friends.

Steve’s loved piano ever since he can remember. His mother has a photo of him sitting at a piano at 3. As a boy, when not playing baseball or soccer, Steve practiced piano. He played Beethoven and Bach by age 10. When he was “tall enough to reach the pedals,” he played the pipe organ in church. “ It was useful for making good side money.”

At 12 or 13 Steve recalls his brother’s earning $4.95 an hour working at a grocery store. Steve made $22 an hour teaching high school students. By the time he reached high school, Steve says, he “never had a real job.”

At SUNY Purchase, Steve studied with organ and music theorist Anthony Newman who’s collaborated with Leonard Bernstein, Itzhak Perlman and many more legends. Steve says, “To be a good classic pianist requires a ton of practice. From the time I was a teen through my mid- 20s I averaged 6-8 hours a day. To play a Beethoven sonata requires hundreds of hours. I never walk by a piano without playing it. I’m very improvisational. Give me a request—”Let It Be,” “Rocky Raccoon”—you name it, I’ll play it. It’s a cool party trick.

“My mindset about a piano is: this is only alive when I’m playing it. Music is a combination of soul and artistry.”

Steve’s wife, Michelle, teaches third grade. Their children, Piper, 10, and Sophie, 6, have taken music classes since they were babies and “understand music is a natural part of their lives.”

Steve, 44, has the same enthusiasm for his work at All-Star. He deems the McGillicuddys “two of the most dedicated people on the planet.” About their approach to developing trauma informed foster care, Steve says, “I feel as though we’re on the path to something transformative. Graci and Dennis are aware this is more than the fulfillment of their dream. It will grow into something bigger than both of them. The seeds have been planted.”

While in most foster families, biological siblings are separated, at All-Star they stay together. The agency educates, supports and empowers the adults around a child to promote “safe, trusting relationships.” Programs are implemented and researched with the aim of creating intervention models that can be replicated around the country.

“All-Star transforms the role of the clinician not only by relating to children but by working with foster parents, tracking outcomes and producing data to back up their approach.”

A Clinical Support Coordinator works with the child welfare system to “break down silos and collaborate” on occupational therapy. All-Star doesn’t wait months for Medicaid approval. The Clinical Support Coordinator works promptly and directly with school and court systems “to make sure kids get what they need.”

In playing the piano and in fundraising, Steve taps into both sides of his brain. He enjoys working with many talented people who’ve made Sarasota their home. “We’re lucky to have people who were CEOs and giants of industry now participating to make our community a better place.”

Thanks, Steve, for sharing your story. And for making beautiful music—literally and figuratively—in Sarasota.