.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

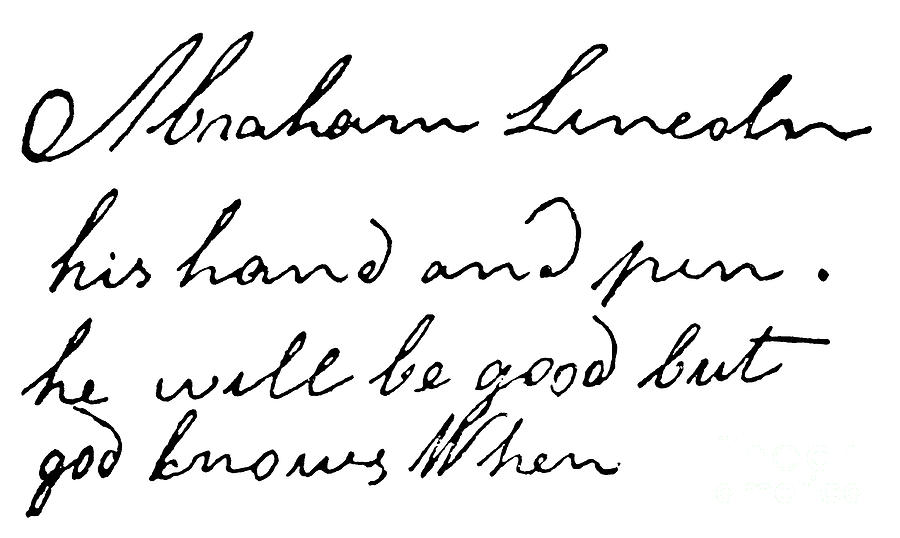

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you, from him but not by him.

Tis the wink of an eye, ‘tis the draught of a breath,

From the blossoms of health, to the paleness of death.

From the gilded saloon, to the bier and the shroud.

Oh, why should the spirit of mortal be proud?

William Knox

Lincoln quoted this poem incessantly. But for a meditative man so focused on death he also kept in his mind the uncertainty and mystery of birth. As a young boy he saw his infant brother be born—and die. His mother died when he was nine. His older sister died in childbirth.

There it all was: birth and death.

One of his very earliest memories was to see his doubled pumpkin seeds, planted in every other row in the field, all washed away by a sudden storm.

There it was again: life beginning and ending.

He, himself, was rescued from drowning, age seven, by a friend. He’d fallen into Knob Creek, having slipped trying to cross on a log, “raccoon-like.”

There was, then, that poem by William Knox that so marked his adult life. Folks for years thought he had written it. The theme really was a devotional teaching. It was about how foolish it is for mortals to be proud. A kind of one-sided Ecclesiastes. There is always a time for death.

Lincoln’s spiritual life was born in a very un-American way, in the mysterious tradition called the via negativa. For all his jokes, joy and vitality it was his reaction to suffering and death that gave birth to his spirit.

He faced the frontier prairie, so infinite and yonder. What then was this finite life, with its reed-like frailty, its diseases, snows, hurricanes and vast primeval forests? Where was security and confidence? Yet he tells his young friends that the life of an ant must be as precious to it as ours is to us. But why was there the ant at all?

A precious and positive spirit began in Lincoln. While so much negated life, he still valued it, and himself. The spiritual life of Lincoln seems to begin with his many ways of saying to himself and others: “In spite of all this—I will be.”

That “I will be” was big, bigger than all the nothing all round. The big life that grasped him was a sense of Yonder, of Fate, and even, for a long time, a fate without God. And he was grasped by a precious sense of America and the idea of the equality of people.

America, and eventually his sense of God’s judgment, would call upon all the courage any one person could be asked to have. There was always in him a Yes and a No.

So where’s the courage in all of this? It is in the Yes that comes after the No.

There were many forms of No in his life. We have plenty of evidence of the prankster, the jokester, the boundary pusher. The rebel “I will be” was often very close to Albert Camus’s “I rebel therefor I am.” Eventually he became a rebel with a cause. As a rebellious boy he said No to hunting, swearing, drinking, unlike his friends.

The Yes seemed called up by the incidents in his life—like that ant. He said Yes to reading and writing and kindness, generosity, unlike most of his rough cohort and certainly his hard nay-saying father.

Lincoln’s nay-saying father is a key to Lincoln’s stalwart courage. Lincoln’s life schooled him in a dark fight. The great unrecognized wrestling match in Lincoln’s development was the physical and spiritual and nearly silent one he had with his father.

Thomas Lincoln was not a bad man, he was a hard man. He was built like an ox, was full of practical skills with carpentry. He had a dogged sense of wanting to make his own way in life, in a free way. He belonged to the Free Will Baptist church, was a leader, built their pulpit, and had himself and wife fully consecrated in that Calvinistic but institutionally free church.

Yet his life said No to everything that Lincoln was: a reader, a dreamer, a thinker, and a mind and spirit in quest of everything that America offered: self-government, the rule of law, freedom of mind and spirit, and freeing economic opportunity for the common man.

Lincoln said No to his father’s church and way of life. The most uncharacteristic act Lincoln ever performed was when he refused his dying father’s request to see him. It was a massive No.

The other No that was addressed to him was his mother’s death. Then all the other personal deaths, average for the age. These deaths were life’s No to him personally. And then the massive number of deaths in the Civil War. These deaths were a No to America. Lincoln had the courage and capacity to face that toll because he had his sad and melancholy spirit. Paradoxically, the courage of his sorrow kept him going. He was in touch with the power of these deaths, and in his daily way he found a way to say No back to them. No, in spite of all this, “I and we will be.”

Lincoln kept gazing at the impenetrable darkness of fate. His mantra poem, quoted above, was really an affirmation. Paul Tillich, the theologian, says in The Courage to Be, “Man’s knowledge that he has to die is also man’s knowledge that he is above death.”

Sin and death are not the last word. To live such an affirmation grasps one into the yonder and eternity of what Lincoln finally called the Living God.

His courage came facing the anxious quiver of life. Such a way of being can hold us, like Lincoln, down in honor to the latest generation, to eternity.

This is Duncan Newcomer and this has been Quiet Fire. The spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.