By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

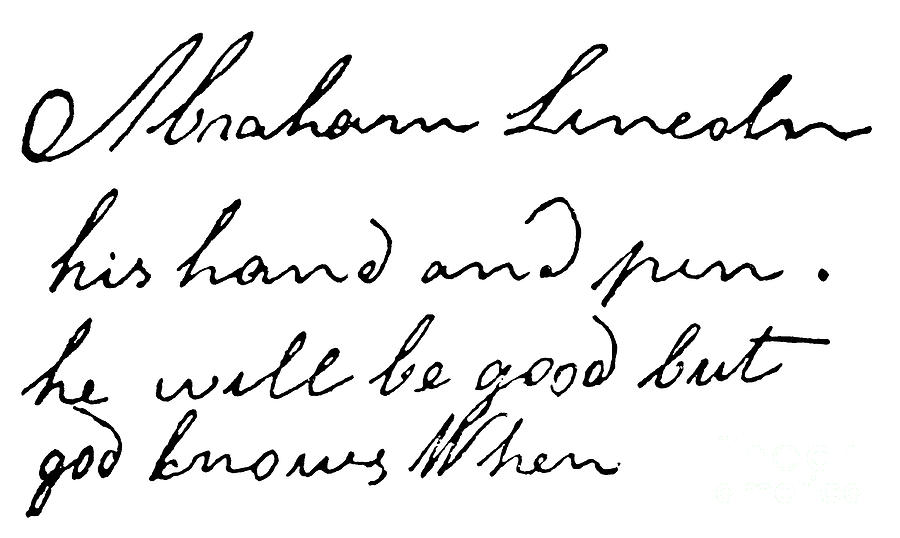

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you, in his own writing—the very first we have. If you cannot make it out (above), the text says:

Abraham Lincoln

his hand and pen

he will be good but

god knows When

We begin to see the spiritual life of Lincoln when he first takes hand to pen in school. This is the beginning of what we can see. Perhaps he is plagiarizing every other school boy. But he is putting down in ink what we forever see in him, his sincerity about being good—and his thrift of pride. He doesn’t know “When” this will ever happen, his being good, and so between him and that un-capitalized “god” he sees himself on the poor side of goodness. And we love him for this humility.

We love him for the ethical impulse. This man would not be an artist, although there is Truth and Beauty in his addresses. He would not be a saint or savior, although there is purity in his long-lived self-sacrifice. He would just be Good, addressing the Common Good with his personal honesty.

Lincoln once told a group of aspiring young lawyers that they should try to be honest lawyers, and if they could not be honest lawyers—then, just be honest men. The reason Lincoln becomes more than an honest man himself, the kind of honest man we might see in a Dickens novel, is because the school he went to in order to become an honest man was the school of severe suffering.

We have been looking, then, at the boy who suffered and the young man who suffered, and have been asking where does the courage to be, the courage to be Lincoln, come from in such a curriculum, or is it a catechesis?

The courage to be tells us more about the spiritual life of Lincoln than his faith to believe. His spiritual life is lived out in the courthouse and the White House. He is a lawyer and a politician, not a priest or preacher, although he may have become a prophet. So in his secular life and especially in his childhood and youth we look to the natural events of his life, sharp events of suffering.

We have named two in this series, death and isolation.

His mother’s death was from an epidemic that haunted the frontier for years. It was called “the milksick”. As well there was the death of his younger brother as an infant, and his older sister in childbirth. These deaths belong to his youth. They happen before two of his own sons, and the multitudes of the sons of America, are taken.

We have also looked at his isolation and confinement. At age 10, for several months, he and his cousin and sister survived in their Indiana cabin with a dirt floor, wearing animals skins, hunting game for food and wood for warmth in the winter of 1818 while his sole surviving parent went to find a new wife back in Kentucky. And then a dozen years years later, there were many months of the infamous “Winter of Deep Snow” in 1830-31 in Illinois that froze the whole prairie in a bizarrely deep and steady snow and ice storm, trapping hunters and animals outside. Six-foot drifts trapped families inside, including Lincoln, age twenty, with his father and step-mother and half-siblings in their log cabin in a new state.

This is what a professional in the field of childhood spirituality, Sally Thomas in Maine, has said about such traumatic events as these:

1. This is how Lincoln became an Old Soul at an early age.

2. This is where he begins to take that inner soulfulness and make of it an outer union of people, how he was a social engineer creating healing relationships for the wounds he suffered.

In a recent webinar sponsored by New York Disaster Interfaith Services on pastoral counseling in times of trauma, the presenter, the Rev. Fred Meade, reminded us that we cannot give to others what we do not have ourselves. Self-care and our own ability to find our inner rock are critical to the spiritual task now before so many clergy and care givers.

Sharing, the giving of spirit, is the social dimension of the healing of Lincoln’s childhood traumas. Healing in relations goes inward and outward. We may not have seen it as social engineering, but it is the giving to others of what they need to re-weave the social fabric of life.

For Lincoln the virtue of politics is just that. It is, as he said in his last address, to bind up the “nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan.” We do that so that we ourselves “achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

He once had enjoined Congress to recreate a nation that the “world will forever applaud, and God must surely bless.”

The healing of Lincoln’s youthful trauma—as a spiritual process—was his relationship-rebuilding within himself and with others. He, also, could not give the country what he did not have. There is evidence that when we look at his childhood spiritual life, we see a young spirit become an old soul not unlike his healing stepmother who took a divided, blended family and made it one house, one home, a union, that he carried within. His Private Secretary John Hay called President Lincoln, “The Ancient.”

It can be said that all spiritual leaders—from the German Martin Luther and the Reformation to the American Lincoln and our Civil War—that they both gave the spirit of God as it was shaped by their most internalized parent. Martin Luther divided Europe and the Church with his great and holy anger against his father. Lincoln rebirthed this nation with the great and sacred love he had for his two mothers.

Trauma in the spiritual life of children, as Christian educator and spirituality researcher Sally Thomas has said, goes to the existential limits that the child experiences: aloneness, death, freedom and purpose. But she says, “Because each person’s experiences and how they are shaped to respond to them are unique, spiritual development does not follow any developmental or predictable pattern.”

We shall see that in a coming episode on the paths of an unpredictable Lincoln and an unimaginable Joan of Arc.

But even without a pattern, as we see in the biblical prophets, Sally Thomas adds from her work with the Godly Play curriculum (by Jerome W. Berryman. Church Publishing): “Prophets come so close to God and God comes so close to them that they know the most important things. And they are all around, maybe even sitting in our circle right now.”

Scholars differ on whether Lincoln was a prophet, but no scholar can say he was not close to God nor that God was not close to him—and that he did know and tell us the most important things.

This is Duncan Newcomer and this has been Quiet Fire—the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln