SUNSET SATURDAY, APRIL 20: The most holy Baha’i festival worldwide is the 12-day period known as Ridvan—and it starts today, with the First Day of Ridvan.

Named “Ridvan” for “paradise,” this sacred festival commemorates Baha’u’llah’s time in the Najibiyyih Garden. After he was exiled by the Ottoman Empire, Baha’u’llah spent time in this garden and, here, made the first announcement of his prophethood. For Baha’is, Ridvan is the “King of Festivals,” and the first, ninth and 12th days are occasions for work and school to be suspended.

RIDVAN: BAHA’U’LLAH AND THE NAJIBIYYIH GARDEN

The story of Ridvan actually begins years before Baha’u’llah revealed his identity and took up temporary residence in the Najibiyyih Garden, with a man who called himself “the Bab” (translated, the Gate). The year was 1844 CE when Siyyid Ali-Muhammad, of Shiraz, made the proclamation that he was the Bab—and that a Messianic figure was coming. Nine years later, the man known as Baha’u’llah experienced a revelation while imprisoned in Tehran, Iran: he was the Promised One foretold of by the Bab.

After release from prison, Baha’u’llah settled in Baghdad, which was becoming the center of the Babi (followers of the Bab) movement. Though he made no open claims related to his revelation, Baha’u’llah slowly began attracting more and more Babi followers. The growing Babi community, along with Baha’u’llah’s increasing popularity, caused the government to exile Baha’u’llah from Baghdad to Constantinople. (Learn more from the Baha’i Library Online.) After having packed his things, Baha’u’llah stayed in the Najibiyyih garden to both receive visitors and allow his family sufficient time to pack for the journey.

Precisely 31 days after Naw-Ruz, on April 22, 1863, Baha’u’llah moved to a garden across the Tigris River from Baghdad with his sons, secretary and a few others. In the Najibiyyih Garden, Baha’u’llah announced his prophetic mission to a small group of close friends and family. In addition, Baha’ullah made three announcements: that religious war was not permissible; that there would not be another Manifestation of God for 1,000 years; and that all the names of God are fully manifest in all things. For 11 days, Baha’u’llah stayed in the Najibiyyih Garden. On the ninth day, the rest of his family joined him; on the 12th day, the entire group departed for Constantinople.

THE ‘MOST GREAT FESTIVAL’

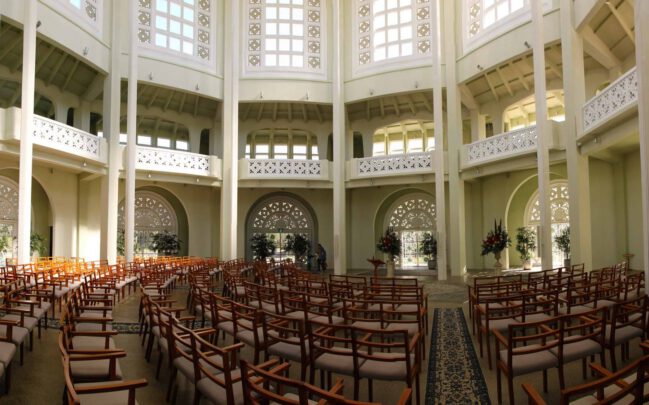

During Ridvan, those of the Baha’i community gather, pray and hold celebrations.

In addition, Local Spiritual Assemblies—that is, the governing bodies of Baha’i communities worldwide—are elected on the first day of Ridvan.

NEWS: Notre Dame Law School recently held its third annual Interfaith Dinner, noting the observance of multiple holidays, including Ridvan. Read more here.